Similar Posts

There is a long tradition of relief sculpture in the Orthodox Church’s liturgical art tradition, but very little in the way of three dimensional sculpture. Can sculpture in the round act like an icon, leading us through itself to its prototype?

Although, for reasons discussed below, the Orthodox Church is unlikely to adopt sculpture in the future, the tradition of using statues in Roman Catholic and Anglican churches is likely to remain. Is there some way of restoring sculpture’s iconographic role and style such as it once had, for example in the Romanesque times? I do not argue here for an introduction of statuary into Orthodox worship, but want rather to open a discussion about how the existing statuary tradition within Catholic and some Anglican churches might be made more iconographic.

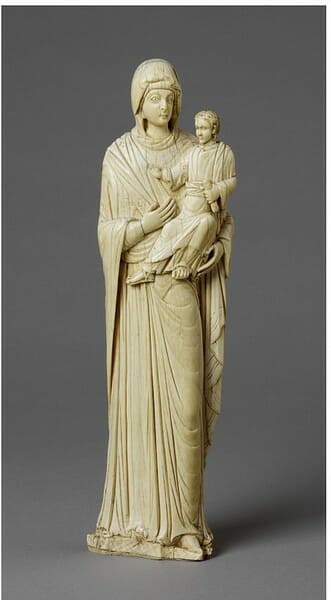

I have been prompted to think about this question since being approached by the Chapter of Lincoln Cathedral to carve a sculpture of the Mother of God and Child for the Cathedral’s Our Lady of Lincoln Chapel. They wanted this sculpture to act liturgically, as an encouragement to prayer and not merely as a decorative work of art. I accepted the challenge and have been commissioned to design and carve this two metre high work in limestone. The half size maquette you see illustrated was modelled in clay and cast into plaster.

I would like to first explain how I have tried to make this particular sculpture iconographic, and then discuss the pros and cons of sculptural work in churches in general, with a positive emphasis on ways that it can be made to work liturgically in non-Orthodox churches.

The Our Lady of Lincoln sculpture

The following passage is taken from the explanatory leaflet that the Cathedral Chapter asked me to write, and outlines the theology behind the work’s design:

“Behold, the virgin shall conceive and bear a son, and they shall call him Emmanuel, which means, ‘God is with us’.” (Mathew 1:23)

This sculpture of Our Lady of Lincoln aims to embody the words quoted above, that “God is with us”.

On the one hand it affirms Christ’s divinity. He is shown surrounded by the vesica, which symbolizes heaven. He holds a sphere, symbolic of the universe which He created and sustains by the word of His power. Although clearly a child, He is also shown as a small man, indicating that while fully human He remains the pre-eternal God, the Ancient of Days. He raises His right hand in blessing.

On the other hand the sculpture also affirms that this same God has become human, has become like us. The heavenly vesica is also the Virgin’s womb. God has become a little child, held in the arms of His mother, dependent upon His mother.

But the sculpture and the Our Lady of Lincoln Chapel will not exist merely to remind us of past events. The aim is to help each person who takes the time to enter the chapel, contemplate and pray, to become a “God bearer”, to experience Christ in their hearts. Mary looks at us, saying, ‘Let Christ be born in our hearts’.

The sculpture’s design is also rooted in place, in Lincoln Cathedral. The garment drapery in particular is inspired by the rich Romanesque carvings found in this wonderful cathedral. The rhythmic curves show that God’s incarnation in the flesh also transfigures the whole material world, restores it to harmony, fills it with His glory. When Christ was transfigured, His garments as well as His face became “dazzling white”. The vesica shape is also drawn from the Cathedral, from the 12th century seal matrix which is one of the oldest and most treasured objects in the Cathedral’s possession.

As well as commissioning the sculpture, the Chapter are also refurbishing the chapel which will be its home. Our aim is to create a space that helps people to be still and pray, to enter the heart and contemplate the mysteries of the Incarnation. We are submitting every element to this question: Will it help people pray? Lighting, furniture design, placement of the sculpture, colouration, all will be chosen with this spiritual end in mind. All the stylistic elements of the sculpture were chosen to embody the words of St Athanasius the Great: “The Son of God became man so that we might become god.”

The tradition of three dimensional sculpture in the Orthodox Church

We turn now to the more general question of the tradition of sculpture in the Orthodox Church. We lack space here to discuss the subject in any depth, so all that can be done in this short space is to raise some arguments people have used against statuary, and then outline some possible ways of mitigating or solving these issues.

As far as I know, there are no Orthodox canons prohibiting liturgical sculpture in the round. The Seventh Ecumenical Council merely states:

We define the rule with all accuracy and diligence, in a manner not unlike that befitting the shape of the precious and vivifying Cross, that the venerable and holy icons, painted or mosaic, or made of any other suitable material, be placed in the holy churches of God upon sacred vessels and vestments, walls and panels, houses and streets, both of our Lord and God and Saviour Jesus Christ, and of our spotless Lady the holy Mother of God, and also of the precious Angels, and of all Saints. For the more frequently and oftener they are continually seen in pictorial representation, the more those beholding are reminded and led to visualize anew the memory of the originals which they represent…

Though this canon neither specifically prohibits nor condones statuary, it does seem nevertheless to favour “pictorial representation” (by this meaning flat imagery in general and not just painted, as it mentions “mosaic, or… any other suitable material” as well as painting).

The commentary on the canons, “The Rudder” by St Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain, certainly makes a case against statuary, but no canons as such ban them. The quote from the Rudder can be read in post 26 in the this link.

St Nicodemus concludes that although statues are not immoral, they do not do the job as well as flat representations. He acknowledges Eusebius’s reference to a bronze sculpture made by the woman healed by Christ of an issue of blood and placed in the basilica of Paneas where it was venerated. But he considers this liturgical use of a statue as “a concession from God, who, for goodness’ sake accepted it, making allowances for the imperfect knowledge of the woman who set it up”. St Nicodemus summarizes his case in these words:

You see here three things as plainly as day, to wit: 1) that the erection of the statue of Christ was moral, and that the Lord accepted it as a matter of compromise with the times; 2) that statues ought not to be manufactured; and 3) that it is more pious and more decent for the venerable images to be depicted, not by means of statues, but by means of colours in paintings. (“The Rudder” by St Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain)

It seems that the argument for their paucity relies not so much on theological principles as on certain practical difficulties in making a fully rounded sculpture work like an icon.

There are some extant examples of Orthodox statuary, some illustrated here, but they are few and far between: two ivory statue of the Virgin and Child, and a 14th century marble “Sokolac Virgin”, still venerated at the Sokolica monastery, Boletin, Kosovo.

I have listed below some arguments against statuary for liturgical use, followed by some suggestions on how within a non-Orthodox context these difficulties might be solved, or at least mitigated.

Arguments against statuary in churches

- A statue can be walked around and therefore can be treated more easily as an object in its own right. A painted or relief icon faces only one way and therefore always invites relationship with the person facing us, whereas a sculpture is generally designed to be viewed from all angles, even the back, which tends to make it be treated as an art object rather than an invitation to relationship.

- Sculptures are rooted in three dimensional space, while painted icons or relief works exist on surfaces, such as walls, ceilings, or containers. For this reason, it could be argued, flat images can act more readily as windows to heaven. The fact that painting’s two dimensionality is one step removed from three dimensional space enables them more readily to open onto heavenly space.

- How do you venerate sculptures? What part do you venerate? The foot, the knee?

- Being flat, painted or relief iconography emphasizes its non-likeness to the prototype as much as its likeness. A sculpture on the other hand is just one step too close to being like its prototype. This is behind fears that a sculpture can tend to act more as an idol than an icon. St Nicodemus observes in his “Rudder” a distinction between icon and replica:

The reason and cause why statues are not adored or venerated (aside from the legal observation and custom noted hereinabove) seem to me to be the fact that when they are handled and it is noticed that the whole body and all the members of the person or thing represented are contained in them and that they not only reveal the whole surface of it in three dimensions, but can even be felt in space, instead of merely appearing as such to the eye alone, they no longer appear to be, nor have they any longer any right to be called, icons or pictures, but, on the contrary, they are sheer replications of the originals. (St Nicodemus of the Holy Mountain, “The Rudder”)

- Unlike relief carving, or paintings which need to be hung or painted on walls, sculptures can too easily become detached from their architectural setting. This in turn can detach them from the larger liturgical drama of the Church and set them to become stand-alone art objects.

Possible solutions to these problems:

- A sculpture can be placed against a wall or placed within a niche so that it can only be viewed face to face. This also binds it to the architectural setting and therefore compels it to remain integrated into the larger liturgical life of the church community (see point six above). The one rare example of a three dimensional sculpture used and venerated within an Orthodox church that I know of, the Sokolac Virgin, is indeed set within an niche.

- A sculpture’s style can be abstracted in such a way as to remind us that liturgical art does not aim to imitate every physical detail, but rather to introduce us to deeper spiritual realities. Examples are Anglo-Saxon, Carolingian, Ottonian and Romanesque sculptures. Two examples are illustrated here: a wooden polychromed Virgin and Child from Auvergne, France, 1150–1200, now in the Metropolitan Museum, NY, and a Lombardian polychromed work in limestone, now in the MFA, Boston.

- The scale and placement of sculptures should keep in mind the liturgical role they play.

- Architectural or furniture elements of a sculpture can be depicted using iconographic perspective systems, such as inverse perspective and multi-view perspective. These transcend rational thought and encourage noetic vision. Also, all the adjustments to proportion made in the painted icon tradition can be used in sculptures, such as enlarged eyes, elongated figures, simplified anatomy.

- As already mentioned, a sculpture can be integrated into its architectural and liturgical setting by such means as being set into a niche or set against a wall, perhaps in front of a blind arch.

Conclusion

Roman Catholic and Anglican churches increasingly look to the Orthodox Church’s liturgical art for inspiration. Any iconographer in the West will find many of their commissions come from sources outside Orthodoxy. Apart from the Lincoln Cathedral commission, I am presently working on the redesigning and frescoing of an apse in a 1960’s Catholic church in London, a mosaic for the Church of Wales, wall paintings for a Catholic monastery in Ireland and a parish in Leeds, and then leading an icon workshop in a Catholic University in Canada. It is clear that we have a role in helping our Christian brethren vivify their liturgical arts. To do this well we cannot adopt a merely negative, critical and polemic stance. While discerning the failings in western liturgical art and the causes of these failures, we surely need to do this in an affirmative, creative way. But above all we need to identify and encourage all those things, past and present, which are good.

Each Orthodox liturgical artist must therefore decide what their role can be and how to play that role. Andrew Gould has for example designed the Catholic church illustrated below, and Jonathan Pageau carved this splendid cross. All this requires dialogue with the commissioner, which in turn necessitates knowledge of western art, architecture and liturgical worship. The Orthodox Church in the West is not called to be a ghetto, but a transforming and transfiguring community.

Given the reality that “any iconographer in the West will find many of their commissions come from sources outside Orthodoxy,” how do you approach the inevitable commissions for non-Orthodox or post-schism saints?

This has in fact happened rarely for me, but when it does I put the inquirer in touch with one of my better Catholic or Anglican students. `

I like the idea of a restrained statuary in our churches. What I mean by restrained, is that our churches ought to be filled with icons and mosaics before we start putting statues in random corners and empty spaces. Placing a beautiful wood statue of the Theotokos behind a candle stand so that the faithful can venerate the statue from a small distance, could ensure that the statue is not taken out of its liturgical context. In addition, we ought to be careful about what kind of statues we would allow in our churches. The hideous, plastic and manufactured statues of Our Lady of Garden Gnomes should never see the light of a candle as are seen in so many modern Catholic churches. In any case, the above carvings are beautiful and worthy of veneration–I would definitely be comfortable venerating them, and would enjoy seeing them in our churches.

As a liberal Protestant pastor I appreciate the best that any religious tradition has to offer. In the case of Orthodoxy it is icons. I write icons for my own use, and have used them at times in worship, which of course is going to take on a different emphasis than it would in Orthodox worship. I would suggest humility, though, in the Orthodox approach to the non-Orthodox when it comes to the increasing Western interest in icons. Yes, Protestants and Roman Catholics increasingly find something of value in Orthodox icons, but it cannot be expected that the tradition of icons will simply be deposited in an unchanged manner into Anglicanism, Roman Catholicism and Protestantism. It will change, and Orthodox Christians must accept that in a reciprocal manner. It’s a two-way street.