Similar Posts

In a comment on my article ‘The Seventh Ecumenical Council, the Council of Frankfurt & the Practice of Painting’, Baker Galloway asks if ‘to develop towards a contemporary indigenous iconography in western cultures’ we need to revisit ‘these medieval (I use the term loosely) periods in our western history, or do we start from where we are today?’ And he gives his own view that ‘I am yet to be convinced that the way forward involves recovering the Romanesque.’

I can’t address this question (well, let me be frank. I can’t address any question relating to painting) without evoking the case of Albert Gleizes. Gleizes took the view that Romanesque art embodied the qualities that were required for a modern religious painting. I realise that the term ‘modern’ – not typical of Gleizes’s own language – might put some readers off so I will quickly explain that he was not arguing for any sort of linear ‘progress’ in our intellectual, moral or cultural lives, though he was arguing for a sense of direction. A direction towards a religious consciousness such as had existed in the Romanesque period.

Gleizes took the view that human societies alternate in their development between two poles. One of them is materialist and this-worldly, understanding reality as whatever presents itself to our mind through the senses, ie as being essentially external to ourselves; the other is religious, understanding that the material, visible world is transient and that it is through inner experience (in particular, he argued through the practise of a craft) that a more permanent reality can be encountered. The first frame of mind he called ‘spatial’, the second ‘rhythmic’. All human societies go through these different phases and of course we don’t expect to experience either in its pure form; we are always in a state of transition from one to the other. One way of judging the frame of mind predominant in any given society is by looking at the artefacts it has left behind, especially in the visual arts, at what it regards as suitable for decoration. The chaos of our present day visual imagination is in his view a consequence of the breakup of a coherent materialist view of the world (‘humanism’) not yet giving way to a coherent religious view.

Gleizes first gave clear expression to this argument in his essay Painting and its laws, published in 1923, about the same time as Oswald Spengler’s Decline of the West, with his similar distinction between ‘culture’ (organic) and ‘civilisation’ (mechanical). And there are also parallels with Wilhelm Worringer’s distinctions between ‘abstraction’ and ’empathy’ in his book of that name, published in 1908. It would be interesting to discuss the parallels and differences there are between these three ‘cyclical’ views of history but that is not my intention here.

Those of us who love the iconography of the Orthodox Church like to think that it is not subject to the twists and turns, the vagaries of history, so typical of Western art but there is of course much more variety than some of us are willing to admit. And whether or not it corresponds to the theories of Gleizes, Spengler or Worringer, our modern admiration for a type of icon painting that prevailed prior to the seventeenth century has a ‘cyclical’ feel to it – it is a recovery of the past. Furthermore, as Fr Silouan has shown in articles in the OAJ, ‘modernist’ painters, and collectors of modernist painting, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were somewhat ahead of the Church in developing this revolution in our sensibility. The zeitgeist is not for nothing in the business.

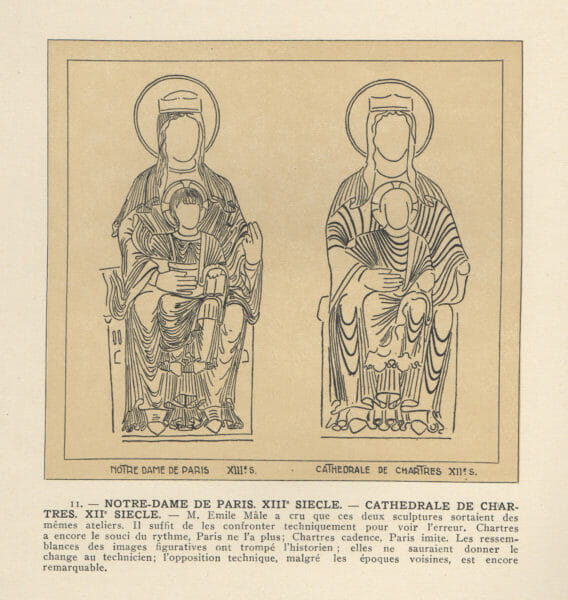

Gleizes argues in Painting and its laws that the transition from a ‘rhythmic’ to a ‘spatial’ art can be seen in Western art in the thirteenth century, in the transition from ‘Romanesque’ to ‘Gothic’. It can be seen most obviously in the treatment of the folds of the garments in Romanesque and Gothic sculpture. The Romanesque garments are an excuse for an elaborate interplay of curved lines; the Gothic folds imitate the appearance of ‘real’ garments on a ‘real’ body.

This is an illustration from Gleizes’s book Form and History (1932) showing a thirteenth century sculpture from Notre Dame in Paris and a twelfth century sculpture from Chartres. In his explanatory note Gleizes says: “Mr Emile Mâle [the leading French specialist in mediaeval art history at the time – PB] believed that these two sculptures came from the same workshops. We only have to compare them in terms of their technique to see the mistake. Chartres still has a concern for rhythm, Paris no longer: Chartres enters into a cadence, Paris is concerned with imitation. The historian has been misled by the resemblance in the figurative aspect; it cannot deceive the practitioner. The difference in technique, despite the closeness in time, is still clearly to be seen.’

It is important to stress that Gleizes did not start out from a study of Romanesque to arrive at his own practise as a painter. Quite the reverse. It was as a result of his researches in the line associated with the misleading name ‘Cubism’ that he arrived at his understanding of Romanesque art. Romanesque art was already coming into fashion, but all too often what was appreciated was the quaint, ‘primitive’ figuration and not the rhythmic interaction of the lines which was, Gleizes argued, the main concern of the artist and of his contemporaries. A highly sophisticated art was being treated as if it had the charm of children’s art.

It is, unfortunately, the quaint figuration that is likely to appeal to modern iconographers wanting to take their inspiration from Romanesque art as it is, alas, the quaint figuration that dominates in much of the so-called ‘Neo-Coptic’ revival.

But what could Romanesque art possibly have in common with Cubism? Cubism marked first and foremost the collapse of the idea that the painter’s job was to situate whatever it was he or she wanted to show in an illusory three dimensional space. This idea and the optical principles by which it was underpinned had sustained painting for some three centuries or more. The question in Gleizes’s mind was to know if Cubism could give birth to an alternative that would be equally strong, capable of sustaining a similar wealth of variety within a common, generally recognised convention. Gleizes did not believe that such a convention would be without precedent in human history. If it was to be true to human nature, it had to be a truth which had already been known in other times and other places. By the early twenties when Painting and its laws was written he believed he had found two essential characteristics for such a development which he called, borrowing the terms from physics (he was at the time moving in a social circle which included Paul Langevin, one of the leading French interpreters of the theory of relativity) ‘translation’ and ‘rotation’. The ‘translation’ establishes the stability of the painting, most obviously through the assertion of vertical and horizontal lines. It is essentially static, a matter of balance and proportion. The ‘rotation’ – beginning with the destabilising diagonal and developing into the curve and ultimately (though this went beyond the argument of Painting and its laws) the arabesque – puts the eye into movement, a movement that is, necessarily circular or spiralling, since the moment it passes outside the frame of the painting it would stop.

For Gleizes this mobility was a dormant faculty of the eye, known to other peoples and other periods of history but lost (or it might be better to say inhibited) with the idea that the painter’s job was to copy the external appearances of the natural world. The realistically painted animals in the Lascaux caves were to Gleizes evidence of a society fallen into decadence. He was suspicious of what he knew of ‘Byzantine’ painting, seeing it as a prolongation of the essentially static art of classical Rome (this is what prompted me to write my article on the Council of Frankfurt). By contrast the rhythmic principle, the ability of the eye to move freely from one thing to the other, was embodied magnificently in Romanesque art. This is what was important in Romanesque painting – not the mere fact that it represented a ‘Western’ sensibility (a sensibility subsequently lost).

Here is Gleizes describing the Romanesque Christ in Glory in Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe in France:

‘Think, for example, of the ‘Christ in Glory’ of Saint-Savin-sur-Gartempe, from the twelfth century, a painting with a grandeur and simplicity of means, a clarity in its ‘doing’ and in its ‘saying’ which cannot be separated one from the other. What an object realised, to achieve the sacred with such apparent facility. The figure of Christ is the centre of the painting, the principle at the heart of every seed; its extension defines the undefined space of the wall … The figure opens up; in entering into movement it becomes an interplay of different currents; the folds of the robe give way to regular spiralling waves; they agree to die in space to be raised again in time; the individual that is shown in the undefined and finite moment is gently turned to the lasting and willed continuity of the person. The cadences become more urgent, the waves stronger, the determination to proceed holds firm, and a diadem of concentric circles overwhelms the image, which is reduced to being a vague memory – right to the point at which the transfiguration is realised, the cadences have achieved their end, the waves come together in the last of the circles, the perfect rhythm, the unique form, eternity. The Resurrection in glory of time and space. The halo is a result of the same operation. It is the fulfilment of the figure pre-ordained in the shape of the head; in its circularity, it spontaneously dominates the eddies of the cadences that have been generated by the different directions opened up by the extensions in space. Ever so subtly, it adds an element that troubles the supreme purity of the rhythm. The halo confirms the gloriole and blends with it unhesitatingly.’ [i]

‘The figure opens up … the individual that is shown in the undefined and finite moment is gently turned to the lasting and willed continuity of the person … a diadem of concentric circles overwhelms the image, which is reduced to being a vague memory …’ This is the problem with regard to Orthodox iconography which insists – and I think must insist – on maintaining the integrity of the figurative image.

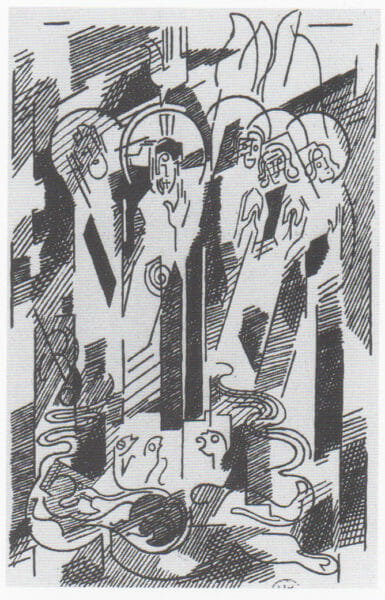

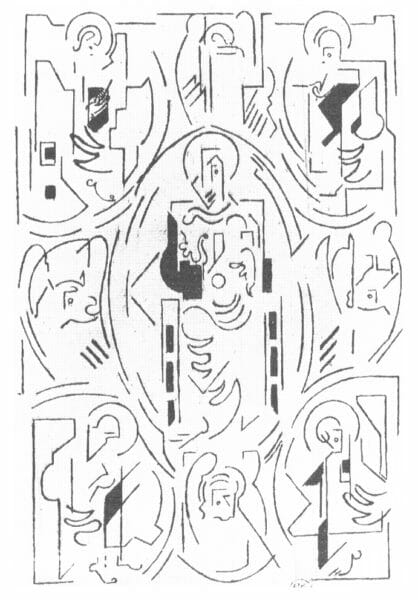

Gleizes was interested in the Mount Athos Painter’s Guide of Dionysius of Fourna and some of his paintings were based on mainstream Orthodox iconography. For example a theophany:

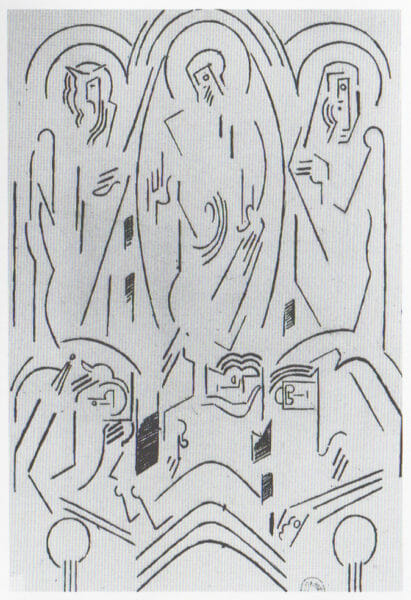

and a transfiguration:

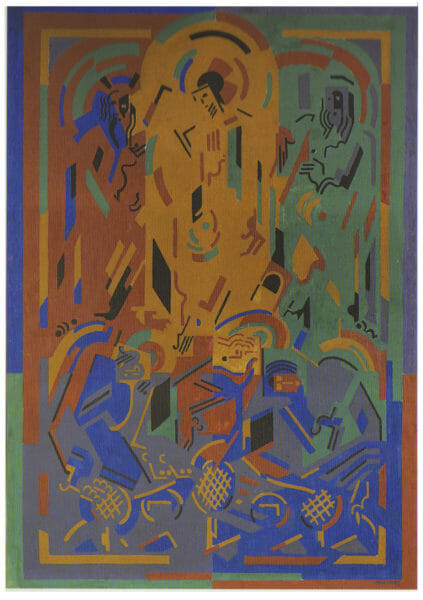

These are both etchings taken from Gleizes’s illustrations to the Pensées de Pascal (1950). He never made a painting based on the Theophany but he did do an important painting based on the Transfiguration, a theme which, because of the theme of light, was important to him:

This is the right hand of a large triptych which also includes a Crucifixion and a Christ in Glory.

This is the etching based on the Christ in Glory with the evangelists and their symbols (a theme of which Gleizes was fond). It is magnificent but it quite clearly could not be used as an object of veneration in an Orthodox church. The Triptych has, however, great importance for me since it was in front of it in the Musée des Beaux Arts in Lyon that, many years ago, I first found myself able to enter into the dance, the movement of the eye that Gleizes announced as the important discovery of Cubism, renewing with the achievement of Romanesque art.

Note, though, the great vertical divisions in the painting which assert at the same time as the mobility, a massive stability. This emphasis on stability is central to my own effort to see how Gleizes’s discoveries could be of use in Orthodox iconography.

What Gleizes was envisaging was a painter’s act that would replicate, or at least evoke, the passage from the senses (aisthesis) through the soul (psyche) to the noetic vision (nous) which, as we know from the Philokalia is imageless: ‘Let the virtues of the body lead you to those of the soul; and the virtues of the soul to those of the spirit; and these in turn to immaterial and principial knowledge’ – Evagrius the Solitary, On Prayer § 132.

Whether or not this is possible for painting in general (maybe it is an absurd pretension. Maybe not) it is certainly impossible for the icon painter who is necessarily, as a matter of humble service to the needs of the Church, stuck at the level of the image and therefore, taking Gleizes’s threefold division of translation-rotation-rhythm (space-time-eternity; body-soul-spirit) at the level of translation. Which is not to say that the higher levels are irrelevant. If we accept this Orthodox anthropology then all three levels are of our nature and therefore always present even in the midst of our most abject sinfulness. And the ‘lowest’ level – the body, the senses, the image – is the necessary springboard (Gleizes used the French word ‘tremplin’) for the rest. But at the level of the springboard – the starting point, veneration of the physical appearance of the Saint – the higher levels can only be hinted at, most obviously in the perfect circle of the halo.

I have often thought that in the days before glasses were invented, older people with failing eyesight entering a church would see only the golden circles of the halos and the ‘decorative’ lines of the radzelka picking out the folds of the garments. The whole figurative aspect would, at a distance at least, be little more than a dark blur. I have quoted Gleizes on the folds of the garments in Romanesque sculpture. Here is Pavel Florensky, writing in 1918 in his essay on ‘reverse perspective’, which shows a good knowledge of the thinking of the painters influenced by Cubism. He evokes:

‘the lines of the so-called razdelki which are painted in a colour different from that used to paint the corresponding place on the icon (raskryshka), most often using metallic paints – a gold or very rarely a silver assist or slaked gold. By thus emphasising the colour of the hues on the razdelka, we wish to say that the icon painter pays conscious attention to it, although it does not correspond to anything physically seen, to any kind of analogous system of lines on clothing or a seat, for instance, but is only (! – PB) a system of potential lines, a given object’s structural lines, similar, for instance, to the lines of force of an electric or magnetic field, or to systems of equipotential, isothermic or other curves. The lines of the radzelka express a metaphysical schema of the given object, its dynamic, with greater force than its visible lines are capable of, although they are themselves quite invisible. Once outlined on the icon they represent in the painter’s conception the sum total of the tasks presented to the contemplating eye, the lines that direct the movement of the eye as it contemplates the icon.’[ii]

That is perfect – or nearly perfect. Florensky the mathematician-physicist sees the lines of force as underpinning, or reinforcing the figurative image. Gleizes would see them as the living spiral running through the figurative image and potentially transcending it, passing from space into time.

But the starting point, the lowest level, the springboard, is still the figurative image and the figurative image, using Gleizes’s terminology is a matter of translation, or, to use his later terminology – measure-cadence-rhythm – of measure. Translation, or measure, is a matter of the organisation of space, in principle static and rectilinear. The straight line has a power and a dignity all its own. Until the painter has begun to have some understanding of this, he or she has no business using any other sort of line.

The vertical is (internally so to speak) the person in front of the icon standing, the horizontal is the ground the person is standing on. Both are stable. The stability is upset by the diagonal. If the whole is not to fall over in the direction of the diagonal it must be balanced by a diagonal falling in the opposite direction.

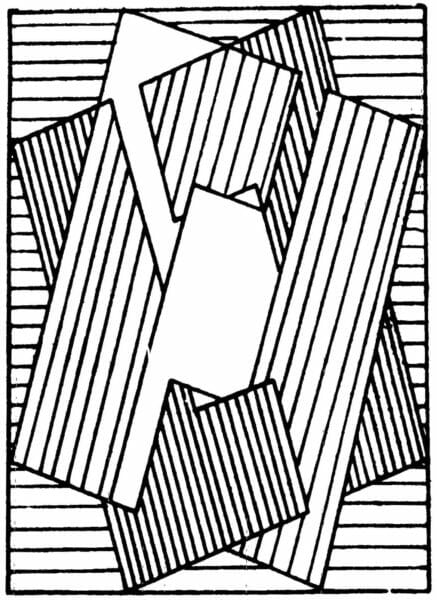

This is the talisman, the essential ABC of pictorial construction, taken from Gleizes’s Painting and its laws:

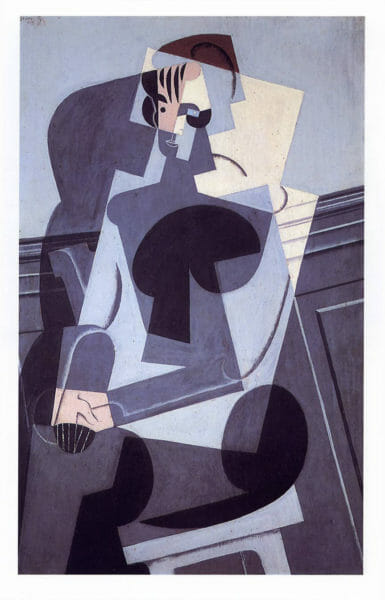

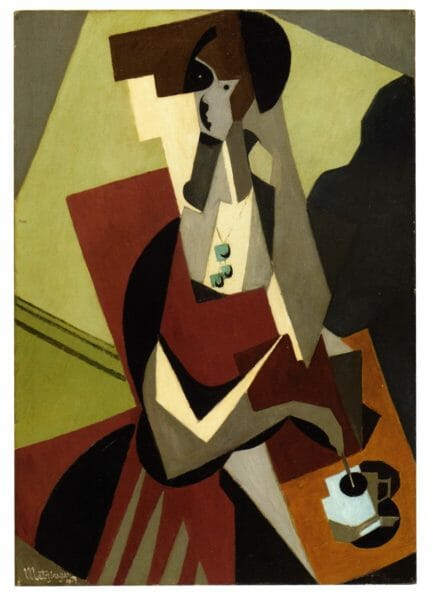

It is derived from the experience of Cubism, in particular what may be regarded as the highest phase of Cubism as a collective adventure, the wartime work of the painters in Paris grouped together under the patronage of the great, but much reviled and neglected, art dealer, Léonce Rosenberg (Gleizes was in New York at the time and not part of this group. He was immensely impressed by what had been achieved in his absence):

Juan Gris: Portrait of Josette.

Jean Metzinger: Le Gouter.

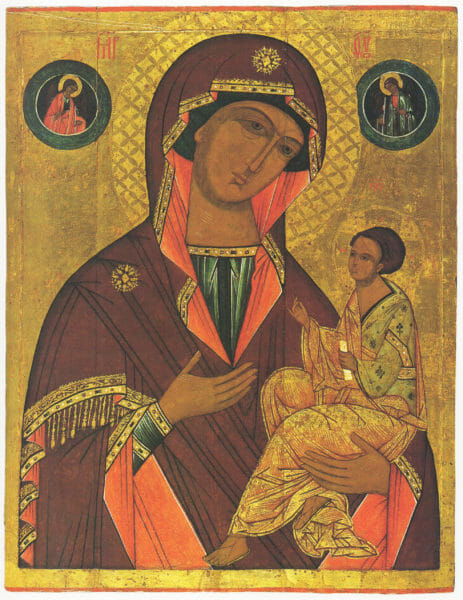

And here is a well-known Russian icon (Vologda, sixteenth century) which embodies much the same principles. Note in particular the force achieved by the parallelism of the diagonal lines:

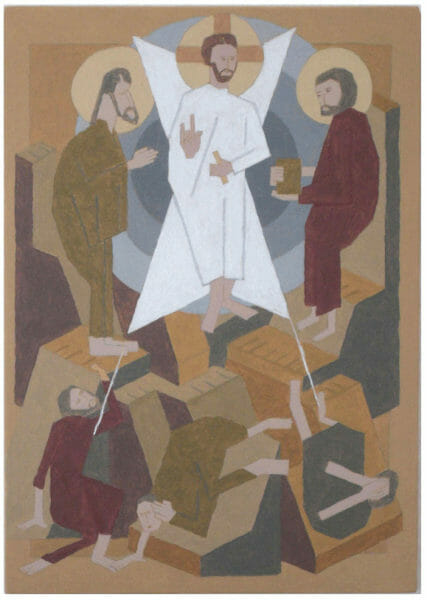

And, since I have evoked Gleizes’s Transfiguration here is my own attempt to use these principles for a (much more conventionally figurative) Transfiguration icon. I have no great pretensions as a painter. I worked for some ten years with a woman, Genevieve Dalban, the person most able to teach Gleizes’s principles, but she was a potter not a painter and I was engaged in a large work of writing, translating and sorting out an archive (as well as grinding pigments and making pottery tiles). She was a devout old school Roman Catholic and not preoccupied with the problem of the icon. I am doing this work in painting because I think it needs to be done and no-one else is doing it:

Of course I am not suggesting for a moment that this is the only way icons can or should be painted. The qualities that don’t interest me – for example, flesh and what we might call tactile materiality – are in themselves very beautiful and there is nothing in the canons to say they can’t be celebrated in the icon. Painters who possess skills I don’t possess may go some way towards combining the two. But I do think the modern icon shares the formlessness and lack of direction of the world about us (less obviously because of the Church-imposed discipline) and that any suggestions for toughening it with a principle of construction should be considered carefully.

Of course I am not suggesting for a moment that this is the only way icons can or should be painted. The qualities that don’t interest me – for example, flesh and what we might call tactile materiality – are in themselves very beautiful and there is nothing in the canons to say they can’t be celebrated in the icon. Painters who possess skills I don’t possess may go some way towards combining the two. But I do think the modern icon shares the formlessness and lack of direction of the world about us (less obviously because of the Church-imposed discipline) and that any suggestions for toughening it with a principle of construction should be considered carefully.

Notes:

[i] Albert Gleizes: Spiritualité rythme forme, first published in Gaston Diehl (ed): Les Problèmes de la Peinture, Lyon, Editions Confluences’, 1945. Republished in Albert Gleizes: Puissances du Cubisme. Chambéry (Eds Présence), 1969. My translation, accessible at http://www.peterbrooke.org/form-and-history/texts/

[ii] Pavel Florensky: Beyond Vision – Essays on the perception of art, edited with introduction by Nicoletta Misler, translated by Wendy Salmon, London, Reaktion Books, 2002, p.206.

The work of http://tanjabutler.com/ immediately came to mind when I read this article – I have long appreciated the way her work draws on both iconography as well as cubism in seeking to represent scriptural narratives…

Thanks Michelle for introducing me to the work of Tanja Butler, which i didn’t know. I shouldn’t be jumping to conclusions on the basis of a brief visit to the website but on first encounter I would describe her as an Expressionist rather than a Cubist (in the way I interpret that very ambiguous term). As an admirer of Emil Nolde (especially the landscapes) and Alexej von Jawlensky (again especially the landscapes) I don’t hold that against her but it isn’t what I have in mind. The emphasis is on an emotional engagement with the figurative image rather than on a principle of construction that can exist independently of the figurative image, which is what I think is the positive, as opposed to negative destructive, side of Cubism.

Dr. Brooke,

thank you for making some important distinctions that help me. First, that the deposit worth valuing in Romanesque artistry is its rhythmic (as defined above) quality, not it’s naïve forms.

Second, that if rhythmic paradigms are to be employed in Orthodox iconography, they must not work to the obscuring of the person depicted. I do suppose that some measure of rhythmic rendering can be employed by the skillful iconographer to good effect in the making of an icon – perhaps even enhancing the emphasis on the person for veneration – but I am also cautious of attempting to marry the two poles in a given work.

I have a follow-up question, which is to call into question the place of ‘contemplation’ (as defined in this article and your previous article) in the realm of Orthodox worship. My view – though almost everybody knows more about this than I – is that the focus of our tradition of worship is to bring us back again and again to the person whom we venerate, who is closer to us than our own thoughts. What we are striving for is continual repentance every minute: turning our mind to God, showing our deepest truest self to God, turning our real face towards the face of God. This pursuit requires every virtue: love, humility, perseverance, courage, hope, etc. And every form of understanding ultimately pales in comparison to the reality of communion with the person whom we seek.

I am not learned or experienced in these matters, but I am cautious to value the pole or rhythm and contemplation equally with the pole of likeness and veneration (or I prefer ‘communion,’ for the love flows both ways). I do however accept a necessary balance (and spectrum) of abstraction and naturalism in the orthodox icon in order for it to best fulfill its role of connection viewer and depicted, and I suppose rhythmic principles may come into the toolbox of abstraction methods.

Why am I saying all this? What am I getting at? I want us all to be careful not to spin away our time set aside for worship with daydreaming, or misdirect it towards an exercise of impersonal meditation. I believe we all know there is a difference between the activity of looking up at the decorative patterns on the ceiling (noticing their repeats and inconsistencies, their possible symbolic meanings and their standard of execution) and the activity of looking at the face in an icon and begging for help in my brokenness. We also know too that there is a difference between yoga and hesychastic prayer, both in practice and in fruit.

So in the context of a physical environment designed for worship, does cultivating contemplation of rhythms as defined above really lead us deeper into communion with the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, or does it lead us down innumerable rabbit trails of fantasy, theory, memory, daydreaming? “He hath scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts.”

Or y’all may correct me that there a season/time/place for everything?

Forgive me.

Many thanks for this, Baker. I found it very useful and I think you have a good grasp of exactly the problem I’m wrestling with as someone who came to Orthodoxy through engagement with a kind of painting which is in its principle non-representational, and who still regards that principle as useful. I don’t say indispensable. The personal encounter you evoke can occur through an entirely naturalistic, or an entirely Italianate, or a simple ‘folk’ icon. Or of course an icon covered with a riza.

I entirely understand and sympathise with what you say about the danger of spinning off into a sort of New Age contemplation of ‘the decorative patterns on the ceiling (noticing their repeats and inconsistencies, their possible symbolic meanings and their standard of execution)’. In fact one can end up similarly contemplating the damp stains on a ceiling. There is a distinction to be drawn between ‘fascination’ and contemplation. They both involve staring over long period of times but fascination is a sort of hypnosis. It goes nowhere. The contemplation I’m trying to envisage is a reminder of the fulness, the dignity of our human nature, which opens up to the possibility of communion with God.

I see this as one of the great functions of the arts. Since this really is intrinsic to human nature as created by God it can exist outside a liturgical context, outside Orthodoxy and even in the lowest depths of our abjection – a recurring theme in Dostoyevsky. I’ve just been reading Isaac the Syrian saying that the souls in Hell suffer through their love for God. Obviously no work of art can embody the actual experience of communion with God, which most of us only know in a fragmented manner but which finds its highest level this side of the grave in the experience of the deified saints. What we are talking about here is only an intuition of that fulness and it is when we have this intuition that we become aware of how far short we fall, of, as you say, our brokenness.

There are artists who would say we should give expression to that brokenness through a broken art and, outside a liturgical context of course, I wouldn’t totally reject that. But we can also try to get as far as we can towards realising that intuition, to rise as high as we can and I do think that the interaction of stability, mobility and circular form is an aid to doing that, whether in a figurative or non-figurative context. And that the very act of doing it is an act of prayer.

Apologies for a rather sketchy response to the very profound question that you raise.

Peter

Perhaps we should not be looking to combine the two poles in one painting, but rather to appreciate their combination at the architectural scale. I commented previously that I’ve found Orthodox icons with Celtic knotwork details to be unsuccessful, because the knotwork competes with the Byzantine figure, desiring our attention in very different ways. However, on the architectural scale, ornamental borders painted between iconographic murals can introduce rhythmic ornament very successfully.

Metalwork in Orthodox churches (chandeliers, lamps, reliquaries) has always had rhythmic patterns. And in hybrid cases, like a gospel cover, or an embroidered vestment, it is often the case, even in the best historic Byzantine examples, that the ornamentation visually overwhelms the iconography. This is okay for liturgical objects designed to be seen in motion, as the icon could never really be the focus of sustained veneration.

In my series of posts “An Icon of the Kingdom of God – the Integrated Expression of all the Liturgical Arts” I sought to show how each element in an Orthodox church expresses a different aspect of the vision of Heaven. If we consider that panel icons were never meant to be seen in isolation, but amongst ornate metalwork, wood carving, etc, then perhaps we need not consider their lack of rhythmic movement to be a shortcoming.

When I first encountered the OAJ I read Andrew Gould’s series on ‘the Integrated Expression of all the Liturgical Arts’ and was very impressed. I was pleased that this comment gave me an excuse to read them again. I’m giving a talk here in Wales shortly on the Orthodox Church – History, Iconography, and Music, and I shall probably pillage these articles (ideas and illustrations) ruthlessly!