Similar Posts

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God… In him was life, and that life was the light of all mankind. (John 1: 1,3)

Well, with all this commotion on the phrase “to write an icon” on the OAJ, it is hard not to jump in and offer some of my own insight. In reading both Mary Lowell’s first piece as well as Andrew Gould’s answer, it is difficult not to see how there is much bubbling under the surface of this conversation. In two days, Mary Lowell’s post has generated almost 2000 views, for something she herself has called “a tangential subject”. But deep down I think she knows this is not at all tangential. In juggling notions of logos, of image, writing, understanding and human production, what is at stake is the question of revelation/manifestation and how we participate, interact with it and define it.

Mary’s position in defending the notion of “writing” as ultimately translating the greek root graph can be resumed in that icons contain symbols, colors, inscriptions and references all forming a web of theological meanings that need to be interpreted, or “read”.

Andrew’s position in disliking the notion of “writing” is that our relationship with icons is mostly that of an “encounter”, an experience of beauty, an experience of Christ, the saints and their stories and to reduce that encounter to a reading of signs and symbols is to miss the entire thing that differentiates a visual image from a written text.

What is fascinating in this discussion is that it roughly encapsulates the big conflict over meaning which imbued much of 20th century epistemology. On one side there is Ferdinand de Saussure and the Structuralist school which emphasized meaning in the relationships of signs creating structures. On the other side is Edmond Husserl and the Phenomenology school which emphasized direct human experience as an encounter that was in many ways before or beyond “signification”. Like I said, there is a very profound rift in this, and if we pay attention to the underlying tenets we will also see this rift in different Orthodox approaches to liturgy, to the sacraments, to scripture and to the whole of Christian life.

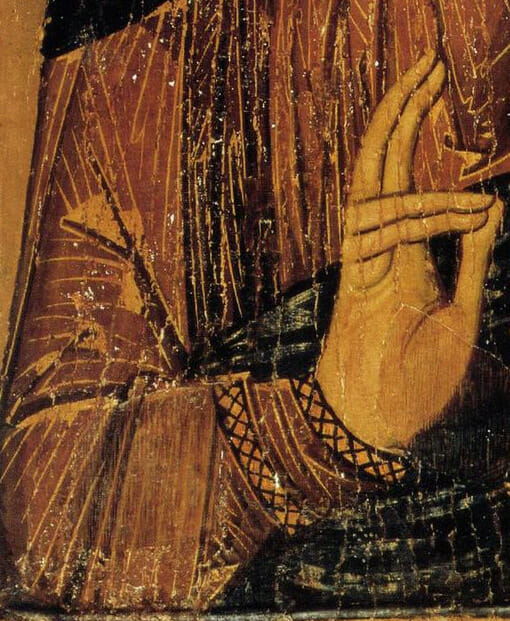

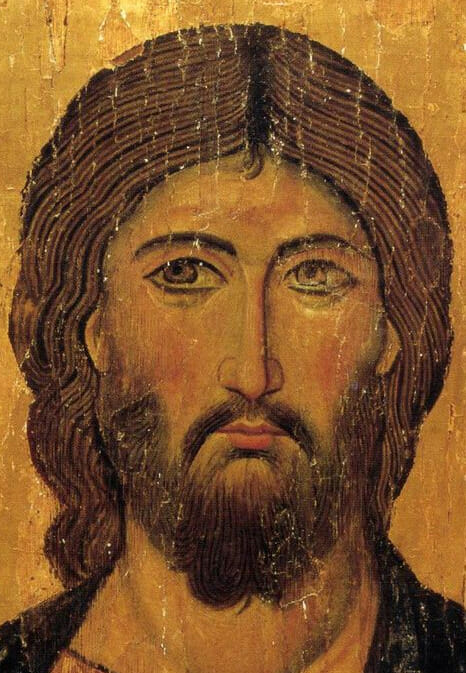

If this discussion was an icon — If this discussion was an icon of Christ, we could say that Andrew is arguing from the “right” side of Christ, the side of the blessing hand, the side which is the direct and relational side of the icon. A blessing can only come from a person, not from a text.

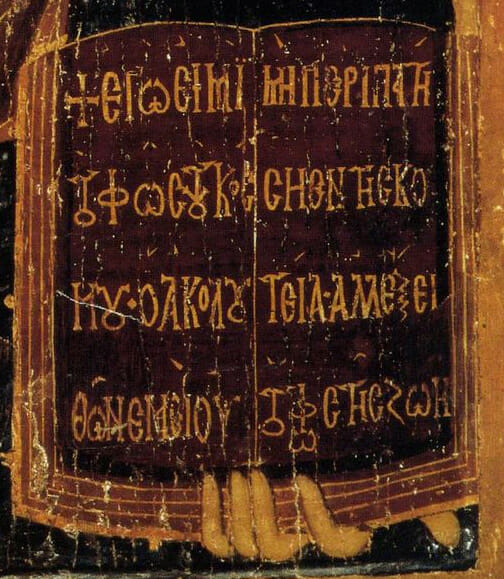

Mary, on the other hand (literally) is arguing from the “left” side of Christ, the side of the book, the side of the fixed and explicit canon, the side of theological understanding. (See my article “Authority on the Right, Power on the Left”).

So what happened? Obviously, an icon contains both of these sides simultaneously. Obviously an icon is a “making present” through beauty, a manifestation of a person or an event, which is why we venerate it. We do not venerate symbols and meanings and theological concepts, we venerate persons and objects which bring us to participate in the life of God. Obviously an icon also contains narrative structures, symbols and codes which cannot be understood by the uninitiated. I dare anyone to show an icon of the “Descent into Hades” to a protestant who has never seen an icon and ask that person what is on it. When St-Paul appears in the icon of the Ascension or Pentecost, when the doors of Hell are beneath Christ’s feet in the icon of his baptism, these are not only “straightforward portraits of holy people and biblical events” (Sorry Andrew).

One of the problems we see in all of this is the reduction of the word graph to writing. This is a very incomplete understanding of the notion. In order to fully understand the notion of graph within the Christian view, we must see it in relation to logos. We must understand the graphy at the end of all those words, not as writing per se, but rather as marking, fixing, organizing, making visible of the invisible Logos. We need to see it as a process of externalization, of manifestation of revelation of the hidden logos in a way very much akin to the incarnation itself. We are also pushed to see this wider notion when reading the verses of St-John’s gospel posted above, where logos is also associated with light. And so the word graph in Greek is not limited to writing, but to image making as well. And we still find it in English with notions like “graphic art”, “graphics” and we even have the very widest meaning I am alluding to when we say that something is a “graphic” portrayal, which means it is a very explicit way of showing something either in text or image. This movement of externalization goes even farther, from fixing the invisible Logos or the invisible Light we must go up the mountain until we reach the “Silence of Tradition”, the “Hesychia” the “Divine Darkness”.

It is precisely this externalization which Vladimir Lossky captures so well in his famous “Tradition and Traditions” where by seeing the notion of “scripture” as the entire movement from the vertical Silence into the horizontal plane of Manifestation, he is able to capture the two opposites presented in the discussion between Mary Lowell and Andrew Gould into one encompassing vision:

Icons impinge on our consciousness by means of the outer senses, presenting to us the same suprasensible reality in “esthetic” expressions (in the proper sense of the word aisthetikos— that which can be perceived by the senses). But the intelligible element does not remain foreign to iconography: in looking at an icon one discovers in it a “logical” structure, a dogmatic content which has determined its composition. This does not mean that icons are a kind of hieroglyph or sacred rebus, translating dogmas into a language of conventional signs. If the intelligibility which penetrates these sensible images is identical with that of the dogmas of the Church, it is that the two “traditions”— dogmatic and iconographic— coincide in so far as they express, each by its proper means, the same revealed reality. (Lossky, “Tradition and Traditions” , In the Image and Likeness of God, p. 167)

So what word can we use? Should we use “write”? Although the word “paint” is a bit disappointing in that it refers to the application of the physical medium rather to a more encompassing process, it is far more connected to how people experience images in our culture. And in looking at an icon, the skill used to interpreting the visual cues, colors, symbols are more akin to how we interpret paintings in general than to how we interpret text. Although not dogmatic, there are as many visual cues and symbols in a painting by Gauguin than in an icon, it is only that they are maybe not anagogical (sorry, Mary.) Even though I can find Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel heretical in its use of imagery, to say that an icon is somehow more “written”, has more to interpret, is farcical. It creates a hermetic category in which we place icons, a category which gives the illusion that we are somehow translating the notion “graph” more fully when in fact it is not the case.

But in the end, as an icon carver I have my own solution. The most direct English translation of the root graph, out of which this whole conflict is born, is the word “carve”. Graph means to scratch or to carve and is a cognate of the Egyptian glyph. So for me, when I say that I carve icons, I win this debate hand down.

You win, Jonathan. Congratulations!

A brilliant evaluation, Jonathan! At one time I would have insisted upon “writing,” asserting the icon’s scriptural identification. And yet, properly understood, our Lord Jesus Christ is our experiential apprehension of the Word, the Word incarnate. As such, applied to the icon and with Christ as our eternal reference, “write” and “paint” are appropriate. Brilliant, Jonathan! Great insights.

Thank you, Jonathan, for pointing out that fine-art paintings contain decodable symbolic content just like icons. I wish I had thought to emphasize this earlier in this discussion. Indeed, as an art history student, I spent many years in school being taught how to interpret the signs an symbols hidden in post-impressionist canvases, Italian renaissance frescoes, Japanese brush-scrolls, stone-age figurines, and everything else in the history of art. The process of ‘reading’ these signs in art is so obvious to me, that I easily forget that many Orthodox people have not thought about art in this way until they encounter icons and learn some iconology. I guess this is why it has always struck me as painfully dishonest when people say iconographers ‘write’ an icon, but that Gauguin/Michaelangelo/Bruegel/Bosch ‘painted’ their artwork.

Good point, Andrew to Jonathan. Of course any serious course in art history aims to lead students toward “reading” a composition, as Response 5 shows in his example of his art instructor’s exercises: “ … ‘reading’ the painting is a key to its understanding.” Any painting. I doubt this process is remote from the way most people look at a painting, even with minimal arts education such as an art appreciation course. With the icon a dogmatic/analogical reading is additionally helpful, though, in fact, it is secondary or sequel to the experience of “encounter”. I dare say that the majority of worshipers are hardly interested in decoding the image, but rather in returning love to the prototype. Do they miss much in so doing or lack for the absence of an iconologist’s commentary? Do they puzzle over whether the artistic mediator of this encounter is “written” or “painted”?

In their indifference to terminology, they are not so far from the “encounter” one experiences with many great works of aesthetic beauty. When I visited the Hermitage in St. Petersburg, I fell behind my touring companions and lingered for an hour before Rembrandt’s “Prodigal,” a depiction of a parable well known to me from the Gospel of Luke. I never made it to the icon collection because of my engagement with this work that conveyed all the drama of paradise lost and regained. If I had never read the scriptural reference, I would wonder who the protagonists were, perhaps begin a search to find out, but I would still be satisfied that I understood the painting.

My objective in the kick-off article was to defuse artificial antagonism over verbiage through a peaceable synthesis of that which is sometimes useful and sometimes abusive. Rather than striving to abolish or concur, marginalize to pretentious jargon or defend on the basis of etymological progenitors, can we not call a truce in the verbiage war over how and why we continue to speak with the gift of many tongues, though Babel’s confusion overthrown at Pentecost?

The language of images is our first language and is inherent (analogically and verbatim) in Genesis 1: 27 “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them.” All of human art in some way depicts the mystery of God and ourselves – crudely, beautifully, rebelliously or worshipfully.

Saint John the Divine does not contradict but elucidates the same: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.”

The challenge for iconographers is how to translate what has been revealed into images that are theologically and aesthetically adequate and appropriate for the encounter of “God with us”. The semantic controversy over how to describe the process of representing the image of God, “the express image of His person,” through His Incarnate Son and His saints, is “painful” only if it leads to theological and aesthetic detraction or worse – addition.

It is possible that the use of “write” for this process both detracts and adds, but I doubt it does any serious damage to the beholder of the result.

I have been following this discussion since the first article went online. These polarized views seem to be fall into two categories:

a. Thesis-antithesis

b. Synthesis

This is where East-West divide is the most visible. The “either/or” approach is more characteristic of the West whereas “both, at the same time” is more typical of the East.

The defenders of “thesis-antithesis” approach firmly stand on the ground that icons are paintings, and that any connection to writing is artificial. There are numerous corroborations of that position, indeed; all are objective, fact-based, and logical.

The original article, however, proposed a different approach, the way of “synthesis”. That is, instead of “either/or”, it is “both,” at the same time. This is indeed the way of the paradox, which is near and dear to the Orthodox. “Jesus Christ is recognized in two natures, without confusion, without change, without division, without separation.” The same paradox is replicated to the minutest facets of the Eastern Orthodoxy, including icons and written manuscripts.

Is calligraphy writing solely? A calligrapher might say it is more painting letters with tools (nibs, quills etc.) than writing.

Is egg tempera painting solely? Daniel Thompson, Koo Schadler and other practitioners of Western egg tempera technique have stated that egg tempera is much closer to drawing than to painting due to its extensive use of cross-hatching techniques.

Although I can see what you mean, I think most people who react to the “writing” appellation, are in large part reacting to a type of exclusive hermetic language which using such terminology implies. I don’t think there is a paradox at all and I don’t see how the two natures of Christ in any way refers to this discussion. It is just that the original word “graph” had a more encompassing meaning, a meaning that came to be divided into several specific concepts in modern languages. This more global meaning of graph, the notion of “marking”, of “fixing” the invisible and more fluid logos is indeed closer to St-Maximos’ vision of external phenomena as pointing to their internal logoi which in turn points to the uncreated Logos. When we use the common language of painting, we can be aware that it is a less encompassing word than “graph” and help people see beyond the words to a deeper meaning. (We could always use the word “depict” which at least does not refer to the physical medium applied). But when we use the word “write” for an image (which is what the word icon means), it is a aberration of the English language, a kind of strange technical use of language. We are inevitably making a statement that normal language of image making does not apply to icons and it is better to use a word which in English always refers to text. If we deny or ignore the fact that in English, the more encompassing notion of graph was separated into several concepts, that using the word “write” in no way captures that more inclusive meaning, that is when we fall into an “either/or” mentality. That is when we suggest that this technical exception to language replaces the usual common language of image making. Better to use the normal language of images used in the English language which does not have any pretension attached to it. But really, I think most people don’t mind when the word “write” is used. What bothers us is that little look that comes when you say “paint”, that little pretension which people have in thinking they understand something simply because they use a strange and unusual word to name it.

Thank you for such a complete discussion. I think the use of the word write and paint can be simpliefied depending on what technique you are using. The petit lac technique relies on pooling colors. In this technique it is necessary to mark outline of each separate color with a scribing tool, an awl would do. The lines marked, inscribed, will prevent colors in each petit lac from bleeding into the neighboring colors.

Paint seems to have some negative connotations due to the history of Western art from the nineteenth century. Suddenly with cubism and impressionism, all the ‘rules’ of painting were turned upside down.

I prefer to use the work make. I make icons. It is a process where the iconographer brings forth an image from as yet an untouched surface by working with pigments or carving. It is manual and spiritual labor.

Thanks Mary and Jonathan and others

Far, far, away from the scholarly side of the issue, I can agree with his statement about that “little look.” There seems to be a certain mentality that often is evinced by the partisans of “write.” I have mostly heard the that word used by recent converts who also like to “discuss” theology … preferably “modern theology.”

“Western captivity” being another preferred concept.

Our Bishop is a wonderful and long-time iconographer; an old school Russian Vladika. He was trained as an iconographer by Archimandrite Kiprian (Pshew), a great iconographer of the Russian diaspora. Old school Russian monks do not adhere to American concepts of “kindness,” in that they do not, sometimes, “suffer fools” gladly. I was present when Vladika was asked about whether “writing icons” was the correct term. Usually not verbose, Vladika had sort of a pained expression, and answered,

“Um … No.” Perhaps the fact that this was in the Cathedral that he had painted the entire interior of also had a bearing on his reply …