Similar Posts

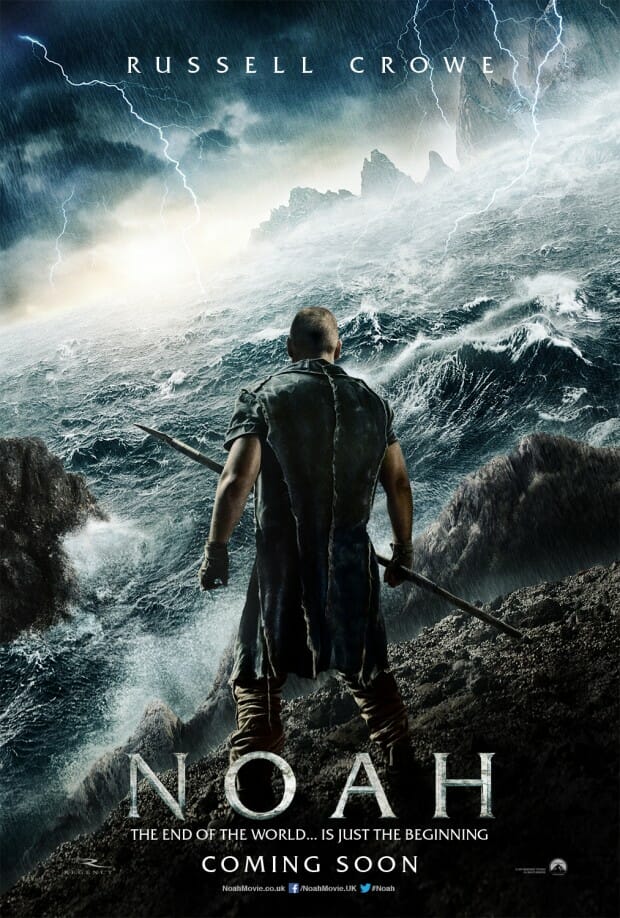

In many of my past articles I have explored the symbolism of death and how it is related in the Bible and by our Tradition to the arts and technology, to hybridity and the foreigner, the serpent, to the cave, to Cain, to animality and to periphery in general. Aranofsky’s recent Noah movie deals intently with many of these same images, and in seeing the often confused and bewildered reactions it has garnered, I am only confirmed in my imperative to make this symbolism more available.

Aronofsky’s Noah is a Jewish movie. It is imbued with a rabbinical approach to the Bible by interpretation through storytelling. It is a very rich vision of the story of Noah, one which boldly takes on the silly literalism of American Christianity and dares to suggest that the Bible is actually about something, manifests something, and is not simply a string of accurate stories that document God’s intervention in the world. Traditional Christians should not be afraid of this. Our liturgy, our traditions, our icons are full of extra-Biblical material and details which act as interpretation, pointing to the meaning of what is already in the Bible. For example, when we say that the skull of Adam was buried under the cross of Christ and that his blood ran down upon it, this is not just some odd historical detail about the crucifixion which is not in the Bible, rather it is a detail that is already interpreting for us what the crucifixion does. Often our apocryphal stories are more fabulous, more miraculous than the Bible, and we are capable of accepting parts of them with different levels of traditional authority while rejecting or arguing over other details from the very same stories. We live with these, we discuss, accept, reject these because our purpose as a Church is not to be “Biblicaly accurate”, but to participate in the transfiguration of creation through the Holy Spirit. In a similar manner, this type of interpretation through storytelling is what Aronofsky’s Noah is doing.

Yet Aronofsky’s Noah is not a Christian movie. It is powerful, rich and complex in its symbolic structures, but there is a crucial element missing in its symbolism, and that is what I want to attract attention to.

Rock Monsters

Let’s start with the toughest part, the rock monsters. In the movie, the fallen angels are represented as huge rock-monsters. This has been an unending source of criticism for the movie. In the Bible and in tradition, there are many suggestions that the cause of the flood, or at least part of its cause is the result of fallen angels, fallen angels that have somehow mingled with men. In the Bible, there is a reference to a mingling, understood as a sexual transgression between the higher and the lower, between the sons of God and the daughters of men. There are two traditional interpretations of this mingling, one is that it represents the mingling of the descendants of Seth with the descendants of Cain. The other is that Angels fell to earth through desire for women and their unnatural relationship caused the giants. In the Enochian tradition, this intermingling of angels and men is also the source of technology, the angels teach men the arts and crafts, modification of nature which is seen as perversion of nature and it is these perversions which lead to the flood. The way to understand this in our own world is that the higher things, spiritual things, truth itself can be denatured and create monsters when they are applied inappropriately, when they “fall”. There is a truth in a nuclear weapon, a truth of God, but this truth has fallen into a monstrous body.

In Genesis, Adam is made by God with dirt/dust and spirit/breath. The result of this perfect union of the substances of the lowest (dirt = earth) with the highest (spirit = heaven) creates a glorious body, a body represented in the movie as golden using a symbolism the Orthodox are quite used to when we think of the halo. Considering this Biblical image, it is quite powerful that in this movie, the fallen angels appear as an improper union of the heavenly (here represented by light) and the earthly. Instead of Adam’s luminous body, the rock bodies are deformed and incomplete. Like the Jewish Golem, they become dark cavernous shells, prisons for the faintly perceivable glory hidden within. And it is these monsters who teach Cain’s descendants how to mine the earth and create cities, iron, all those things the Cain’s line are attributed with in the Bible. They do this to help men, but it turns against them and Cain’s descendants destroy the earth. In the movie, the final representative of the Cain’s line is Tubal Cain who is credited in the Bible of having created metallurgy. The image of iron related to Tubal Cain is important. The first thing Tubal Cain gives Ham (the future cursed son of Noah) to attract him is an iron war hammer/axe, the same hammer/axe Tubal Cain uses as a blacksmith. In this the very symbol of the tool is linked to the weapon, just as the traditional image of Cain changing his till into a spear. Finally the giants use their knowledge to help Noah build the ark, and in this we see the first glimpse of the duality of the supplement, the idea of death and the combating of death by death. We see that both the cause and the solution of the crisis originates in the same place. Finally the rock-monsters are transformed, their “light” is liberated when they they flip things around again, turn against Tubal Cain, acting like a peripheral defense of the ark when it is being attacked, and doing this by brandishing huge iron chains. Iron against iron.

Popular representation of the Golem of Prague, who according to folklore was animated by Rabbi Loew to defend the the Jewish community of the city of Prague. The fallen angels use a similar symbolism in their monstrous rock bodies.

Death and duality

The duality of death is presented very powerfully in the movie. I have written many times about this duality, about the paradox of its consequences. We are shown the garden of Eden and the tree of Knowledge/Life is in fact two trees crossing each other. As Eve tastes the fruit, Adam is “distracted” and looks to the ground to touch the dead skin left by the serpent who has shed it (the word used to describe the serpent in the Bible which is usually translated as “crafty” also means “naked”). And so the fall is presented as this lowering towards death. We know that Adam picks up this “garment of skin”, as this skin is passed down through the descendants of Seth. The skin is wrapped around the arm and used to bless the succeeding generations. This wrapping around the arm suggests of course the tefillin, the leather strap used by Jews to bind the law to their body as a memorial (Exodus 13:9, Deut. 6:8, 11:18), but it also suggests the serpent wrapped around the pole/tree which represents this duality of death, and which I have spoken of elsewhere (The Serpents of Orthodoxy). And so the duality is powerfully brought forth, because when Tubal Cain sneaks into the ark with the help of Ham, it is with this same animal skin that Tubal-Cain will curse Ham in the the final moments in the Ark. So the serpent, that is death, is both a source of blessing and of curse.

Israeli soldier wearing the tefillin during prayer

The duality of Noah and Tubal Cain.

One of the biggest errors in approaching the Noah movie is to want Noah to be the “good guy”, to want him to be the “hero”. This error is also made by some upon reading the Bible, especially the Old Testament. All the human characters in the OT have a dark side, none of them are “the good guy”. Understanding this will help us see things we could not see otherwise and it will help us avoid undue emotion when the character we want to be the “the good guy” does things we do not agree with. We need to see Noah and Tubal Cain as two extremes, two opposites, somewhat as I have explained about the left and the right hand. Noah is the “servant” of nature. He only gathers what he needs from the earth, he does not eat meat, he does not build cities, he does not even farm. He has integrity to a fault. He is like a radical Greenpeace vegetarian ecologist who despises the “carbon footprint” left by man. Noah even chides his son for picking a single wildflower from a hill. Tubal Cain “dominates” nature. He is passionate, powerful and preaches human will. He eats raw meat with blood, digs mines, makes cities, weapons and war. He is like a gas-guzzling, gun-toting industrialist who hates those hippy idealistic tree-huggers. Many people have been annoyed by the portrayal of Noah (especially the gas-guzzling gun-toters), but just as it is Tubal Cain’s excessive approach to the role of Man and creation which has led him to do anything necessary to preserve his lineage, so also it is Noah’s excessive attitude towards creation, this excessive diminution of Man which leads him to believe he should kill his own family. Noah doesn’t just want to circumcise Man, he wants to castrate him. Both go too far.

There is in fact a very powerful scene in the movie, in the very moment where Noah wants to kill his family to eliminate Man from the earth. Hidden in the Ark, Tubal Cain has a surprising speech in which he uses the very words of the Bible to say that God put man in the Garden to have dominion over creation. He does this as he bites the head of a living reptile, extinguishing forever that species to assure his own survival. In this moment, both men are shown in their extreme, where they are both right in some way, both wrong in another, but pulled into the radical consequence of their opposition.

What is Missing

This movie understands very well the duality of the world of the fall and death and though it attempts to present one side as being better (Noah’s side), it cannot avoid its own logic in bringing the duality to both its suicidal extremes. So what is missing from this movie? What is missing is the one who is in between Noah and Tubal Cain. What is missing is the Lord who washes his followers’ feet, the King who dies for his subjects, the Shepherd whose sheep obey his voice, but who also gives his life for those very sheep. What is missing is the one who can unite the blood of Tubal Cain with the wine of Noah, who can unite the Garden of Eden with the Heavenly City, who can both die and conquer all at once.

This missing link could also have mended one of the most disturbing aspects of the story. In the movie, the angels fall by compassion, not by desire or pride as is usually posited in our Tradition. This is a very grave inversion. In a similar fashion, when Noah does not kill his granddaughters, it is understood by him as a transgression, as a sin of compassion. How can this be? The real question should be: how can we understand the golden sparks of heaven trapped in the world of the Fall, that world where the Garden is lost and Adam’s glorious body is tarnished? If we see these hidden sparks of divinity coming down by compassion, as a condescension from on high, can we conceive this compassion as anything else but a fall from above, as a breaking of the divine law of Justice, a transgression of the absolute division between Heaven and Earth? It is only in the Incarnation of Christ that these problems can be solved, only in a perfect union without confusion of two fully distinct Divine and Human natures into one single person. In this, the duality of Heaven and Earth is resolved without being annulled, and the glory of Adam’s body is restored at an even higher level than in the Garden. In this we do not have to understand the descent of the influence of Heaven or even technology and the arts as necessarily fallen and monstrous. Rather, when all these descents “remember” their heart, their origin, they can be transfigured, not into dis-incarnated light, but into “resurrected” shining bodies.

And so I think that Aronofsky’s Noah is a powerful movie, because we live in a world that has indeed forgotten the possibility of the Incarnation, a world that has been abandoned to its extremes and Man’s disregard for God’s creation is one of the symptoms of this accelerated Fall. Noah is also a powerful movie because it dives into the symbolic fabric of the Biblical story, the type of symbolism that I will continue to expound in my future articles. The only thing missing is what makes all one, a vision of Christ, the vision of the heart.

Thank you, Jonathan, for taking this movie seriously for what it is. It is, of course, a largely fictionalized bible story – a movie about scriptural interpretation. As such, it stands in a long tradition of Orthodox Jewish and Orthodox Christian fictionalized interpretation (midrash, hagiography, and hymnography containing many other venerable examples).

It is strange how many critics have misunderstood this movie. Some Christians ‘thinkers’ have rejected it because they think it exalts a new-age Hollywood environmentalist religion. And yet, the movie daringly shows us the dark extreme to which that religion will take us if carried to its logical conclusion – murder of one’s own family. On the contrary, the story is about the failure and defeat of Noah’s twisted ideas, and at the end, God Himself affirms the choice of human life.

Indeed Noah and Tubal Cain are two sides of the same distortion of man’s relationship with nature. But I am not sure the movie was completely missing the in-between ideal. Noah’s wife and sons were genuinely seeking a middle ground, and often seemed like the only sane people present. And the brilliant character of Methuselah did offer an example of someone fully at peace with creation. Though he superficially resembled a pagan shaman, he did the work of a Christian priest and saint. He offered Noah communion with God through a cup, and healed his daughter with the laying-on of hands. At the end of his life, he came down from the mountain to seek communion himself, which he sought in the form of a wild berry. Like Mary of Egypt, he took communion at the very last moment of his long life, and then received death with great joy, arms outspread in prayer.

At first when I read your comment I did not agree, but I woke up this morning with a hunch, and upon verifying the movie credits I discovered that my hunch was right. Noah’s wife is named Naameh, which means she is Tubal-Cain’s sister. This adds much to your thesis. It also made me consider more closely the last scene, where Naameh is shown working the soil, and it is in this act that she is reconciled with Noah. This also shows what you are saying, because with the fall, God tells man that he will have to work the earth, and in the movie human beings have been reduced to hunters (Tubal Cain) and gatherers (Noah). So by having Naameh find a new beginning with Noah in working the earth it shows the balance we are looking for. I just wish they would have had the sacrifice, or eat meat without blood. But I know that in terms of narrative, it would have cause seizures in the audience, although it could possibly have caused a direct enlightenment like a Zen coan!

I recommend Fr. David Subu’s review, a link to which can be found here:

http://stmaryorthodox.org/newsletter-archives

That is indeed a very good and complete analysis of the storyline in light of scripture and ancient beliefs. Thank you for suggesting it.

Thanks, that is really quite complete indeed.

Thank you both, Jonathan Pageau and Andrew Gould. I appreciate your depth of research and understanding of imagery used to carry that information. Most people these days do not think symbolically and thus miss so much of the Judaeo-Christian tradition. Thank you for widening our vision and thinking.

Bess Chakravarty

Thank you for the kind words Bess.

[…] fine Orthodox visual artist has a much different take on Noah than did Roman Catholic Barbara Nicolosi. Meanwhile, I’m thinking I should re-up for Netflix […]

Jonathan, thank you. I really have enjoyed reading your posts.

I was wondering if you could offer more thoughts on the film/video medium itself, and its proper priority in the material hierarchy you’ve mentioned elsewhere.

Everybody realizes that most of what passes across the “silver screen” (or liquid crystal display) functions as a phenomenon of amusement, entertainment, and objectification. But I think most would agree this merely demonstrates the medium’s perversion, not its potential. Such examples surely do not exhaust the possible uses of film. And I know Orthodox Christians are using film as an artistic medium.

But given your understanding of symbol, material, and iconicity as a liturgical iconographer, I would like to know your thoughts on how Christians can better understand and use film and/or video toward the kingdom of God.

To put the question simply: What is the possible relation between film and the icon?

Thank you,

I definitely think the medium of cinema is worth thinking about in relation to the icon and to liturgical symbolism, but I fear many will disagree with my conclusions. Almost all of my articles on symbolism are about death, about the movement to the edge and to the end, what that looks like and what that means. There is a reason why I am dealing with these issues rather than others, and this is because I am hoping people will notice that our current world is overflowing with this symbolism. It is not that sacred symbolism is somehow not active anymore in our world, but rather it is that we have come to edge of it. So if we look at the symbolism of death in the Bible, in icons and in Tradition, we will find that this very symbolism is the matrix for the contemporary world. And so this is what I think cinema is made of, and the categories you mention, amusement, entertainement and objectification are part of this symbolism, just like the “Carnaval” is associated with the end of a cycle in almost every culture. (For ex. in Orthodoxy, our Carnaval happens on the same day as the commemoration of the Last Judgement, for Jews it is Purim, Romans it is the Saturnals etc.) We see it more and more clearly in “event” movies, that is the big Blockbuster type movies, these (as the latest Noah) are like liturgies for the end of the world… so if we were to give a positive spin to this, and as I have been suggesting in most of my articles, death and glory are mirror images of each other, and one can always be transformed into the other through Christ. So if we were to compare cinema, or rather the potential of cinema to an icon, I would compare it to the icon of the Last Judgement. In this icon, we find a synthesis of almost all the iconographic principles and elements into one, but the same icon can also dwell on the fantastical, the gory, the sensual and the anecdotal… I myself once upon a time wrote an epic type screenplay with my brother that attempted to “flip” death into glory, and sometimes in some movies there is a tiny glimpse of that but it is usually not in “Christian” movies.

That’s a brilliant insight, Jonathan. I have often watched a big action/destruction/apocalypse type movie, and felt overwhelmed by the beauty of it. The slowed-down, visually extravagant cinematography of vast destruction is a lot like liturgical beauty – especially how we prolong the hymns of the Passion in Holy Week, and surround the tomb of Christ in flowers and candles. Even the dark, mysterious, nearly monochrome, palette of such movies is downright Byzantine in character. I think you are quite right to call them liturgies for the end of the world!