Similar Posts

Therefore every scribe instructed concerning the kingdom of heaven is like a householder who brings out of his treasure things new and old.

‒Matt. 13:52

It is the irrational impulses that yearn for innovation.

‒A.K. Coomaraswamy[i]

In a recent correspondence with a friend I was told: “Take the many interviews you have done with modern iconographers. Many of them display stylistic (oft gratuitous IMHO) “innovations”, that are exactly the thing you criticize in Modernist art. Tempering one’s words with a kind of benevolence which I obviously have no knack for does not change the double standard.”

So, is there a “double standard” going on here? In a way I can see how the approach I’m taking in my various posts can come off as “double standard” or “speaking with both sides of the mouth,” as they say. But, believe me, in no way am I expounding “innovation” as an end in itself in icon painting; nor am I interested in somehow “legitimizing” the icon on the grounds of “modernism,” while at the same time reviling Modern art. It’s not that simple. Let me try to clarify the matter a bit.

Fig. 2. Natalia Goncharova, St. George, 1914.

From the album “Images mystique de la guerre.”

Painted lithograph, 32.5 × 24.9 cm. Tretyakov Gallery

Innovation

First of all, the notion of “innovation” has to be qualified. It need not be thought of solely as merely hankering after “novelty” for its own sake, in the way this notion has come to play a role in the history of Modern art, wherein the “individualistic” statement is of prime importance. Innovation in this sense is embraced at the expense of traditional principles for the sake of “self-expression,” whereas in the context of icon painting it is to be understood as a stylistic “development” in conformity with traditional principles. It arises from an actualized participation in the ever-new and ever- renewing source of Tradition. As a living spring Tradition never stagnates but flows continually, remaining the same in its inner depths and yet always bringing about the transformation of what it touches as it courses through time on the surface.

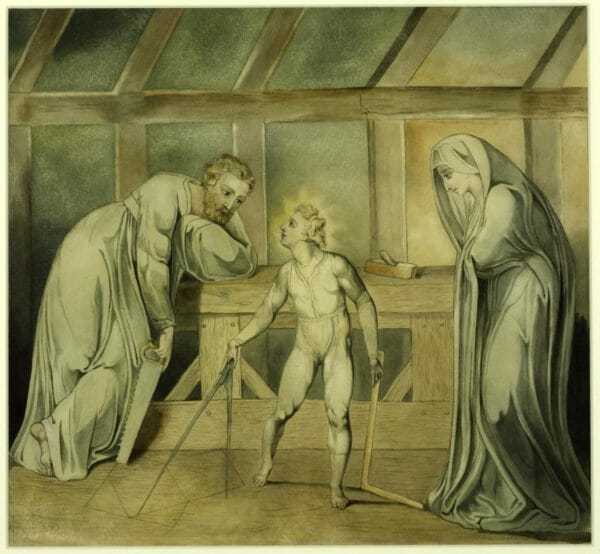

Fig. 3. William Blake, Christ in the Carpenter’s Shop: The Humility of the Saviour.

Watercolour and graphite on paper, 330 x 349 mm. Tate Gallery, London.

Moreover, traditional icon painting presupposes the doctrine of art as skill. The icon painter is to realize the intended idea of the work at hand in its perfection. The degree to which the work successfully accomplishes this end determines its quality. Speaking of the doctrine of art as skill Brian Keeble notes:

Nothing in the doctrine of art as skill forbids or even excludes the possibility, the desirability, even the necessity of innovation. It certainly denies that innovation is itself the purpose and justification of art. It does so in the context of an understanding that sees innovation as naturally arising out of any particular need to guide the application of skill towards the realization of an idea. But innovation in this case would have no license to do more than what is required to realize the perfection of the idea in question. This integral perfection is not only what is compromised whenever innovation is pursued for its own sake; it is also at the vacuity at the heart of the pursuit of “creative freedom”.[ii]

The pursuit of “creative freedom” Keeble speaks of is to be understood as the willful casting aside of the traditional principles, which leads to the kind of irrationality ‒ the arbitrary whims and meaninglessness ‒ now rampant in most contemporary art.[iii] But, on the other hand, the embracing of these principles is what in fact brings about true creative freedom. In looking at so-called “innovation” (using the term for the sake of convenience) in contemporary icon painting, I have sought to emphasize how the principles of traditional icon painting do not exclude the possibility of stylistic and interpretive creativity and variety. These factors take into consideration, inevitably, the temperament of the painters, along with their cultural and historical contexts. So stylistic development or “innovation,” although secondary in importance to the icon’s theology (as the body is to the soul), is not to be undermined as inconsequential ‒ the one cannot exist without the other. It, in fact, demonstrates how icon painting is part of living Tradition. We see this clearly in the whole history of icon painting, in all the diversity of national and local schools. So emphasizing this fact is hardly a “modernist” stance from my part.

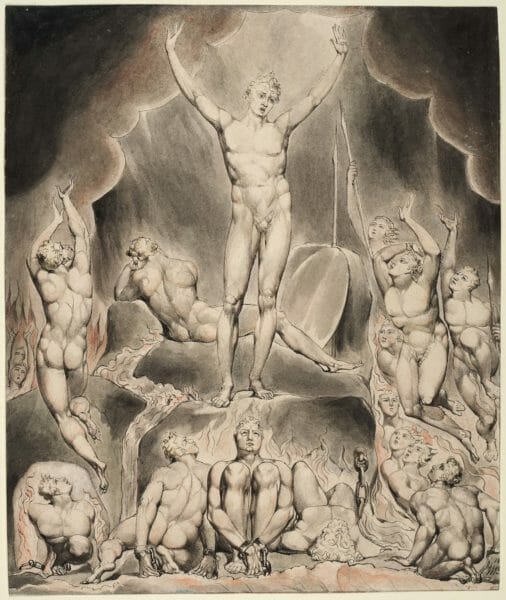

Fig. 4. William Blake, Satan Calling His Legions, 1807.

Illustrations to John Milton’s “Paradise Lost”, watercolor.

Modernism & Abstraction.

Second, when I speak of “modernism” I mainly have in mind an array of symptoms that point to nothing other than a spiritual disease: apostasy, revolt, anthropocentrism, the myth of “progress,” evolutionary progressivism, the cult of “originality,” subjectivism, individualism, “art for art’s sake,” rationalism, materialism, positivism, scientism, nihilism, historicism, relativism, etc. All is flattened, the idea of an ontological hierarchy is abandoned ‒ the Absolute is placed at a lower level. In short, what we have here is a general disdain for Tradition and betrayal of Revelation. Joseph Chiari aptly describes how this general tendency manifests itself in art:

The modernist attitude in art became self-consciously coherent and vocal towards the end of the nineteenth century and is a typical product of western society, afflicted by the peculiar dichotomy due to the fundamental opposition between Christianity and anti-Socratic rationalism which has turned more and more into scientism and pure and simple phenomenalism. This dichotomy has resulted in the partial disintegration of Christianity and in the growth of a type of rationalism which has finally reached the stage of being an end in itself.[iv]

And, ironically, once rationalism becomes an end in itself, at the expense of the nous, the more do things become irrational. Hence, the ever increasing absurdity of conceptual art.

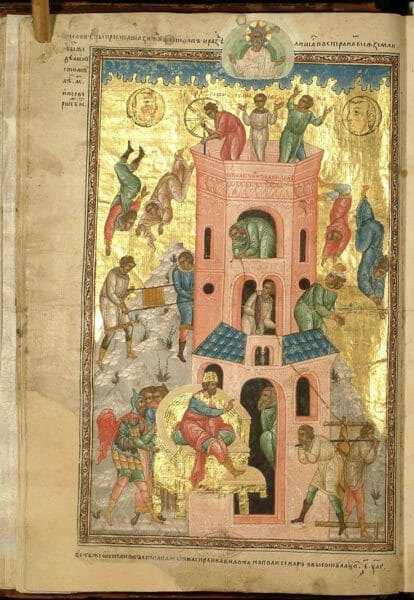

However, modernism is not just a 20th century phenomenon. It’s a “state of mind” that has tempted us from millennia and which cyclically overtakes and destroys cultures in its desacralizing decadence. We see it first in the fall of Satan from Heaven in his self-exaltation against God. Then, in the fall of Adam and Eve in their disobedience to the divine commandment in Paradise. And again, in the wicked state of civilization, in which man became “flesh” estranged from the Spirit, just prior to the Flood. In other words, it’s nothing other than Promethean hubris and the rejection of divine principles; symbolically represented by the “young man” in the parable of the prodigal son, who leaves behind his father’s house, and the Tower of Babel ‒ man’s delusional attempt at self-deification.

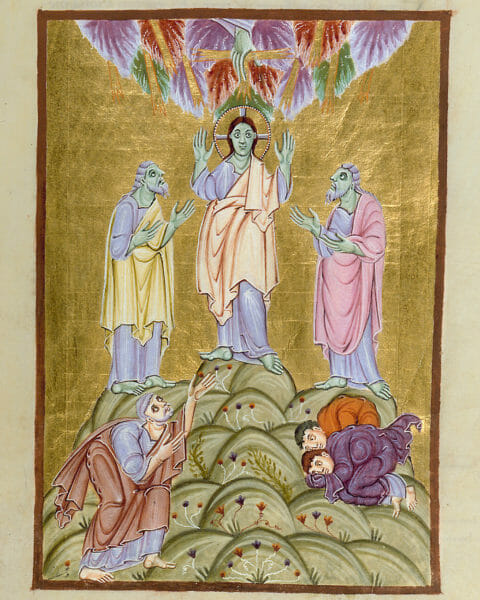

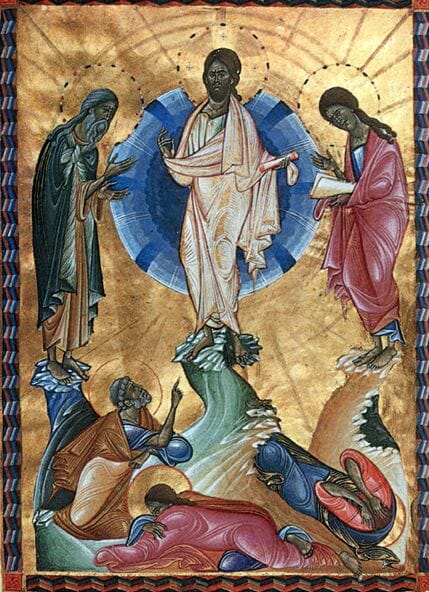

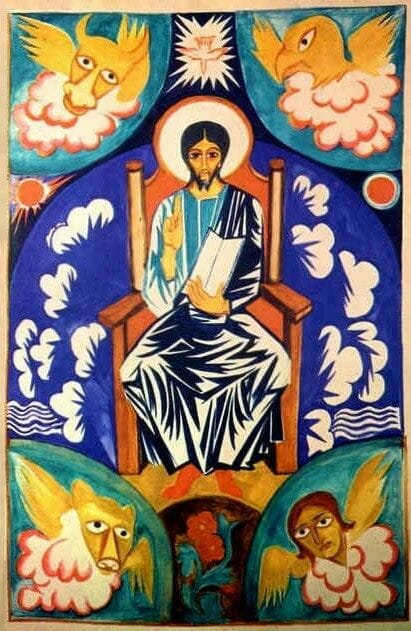

Nevertheless, let’s not forget, that all of this comes in different doses in Modern art. Not everything in it is to be shunned and reviled as evil, not all is lacking in beauty, and not all is doom and gloom. There are exceptions (although they might prove the rule), in particular those aspects in which we find a yearning for the Sacred, and the positive value placed on folk, “Primitive,” Medieval and Oriental art. A salient feature of this general orientation is the important role played in the development of abstract art by the avant-garde’s strong interest in the pictorial significance of the icon. I believe that all of this betrays an unconscious desire for the traditional doctrine of art. Moreover, the avant-garde’s critique of post-Renaissance naturalism and academic art has its parallel in the thought of the pioneers of the icon revival (P. Kontoglou, L. Ouspensky, P. Florensky), albeit the later having its own distinct goals and premises. Indeed, as I’ve mentioned before, there are some aspects of “convergence” between the aesthetics of modernism and the icon. So, whether we like it or not, the irony is that Modern art in fact contributed in the revival of traditional icon painting and the icon, on the other hand, in the development of the avant-garde. It suits no one to deny this historical fact. The question is how we’re to interpret it. And, in turn, our interpretations will inevitably play a role in the current debates surrounding the icon. Be that as it may, speaking of the icon of the Transfiguration and its abstraction Aidan Hart comments on the convergence just mentioned. I think it’s worthwhile quoting him in length:

This icon shows a world shot through with God’s light and glory, a world seen with not just the eyes of the body but with the eye of the spirit. This is surely one of the great callings of art, to unveil and manifest in material form things that are hidden to most of us…

Fig. 7. Transfiguration,10th Century.

From Gospels of Otto III, Reichenau School.

Staatsbibliothek, Munich.

Fig. 8. Toros Roslin, The Transfiguration of Christ, ca. 1265-1272.

Armenian Miniature of the Gospel of Queen Keran (MS 1965).

He then goes on to describe how this is accomplished pictorially in the icon through abstraction and then adds:

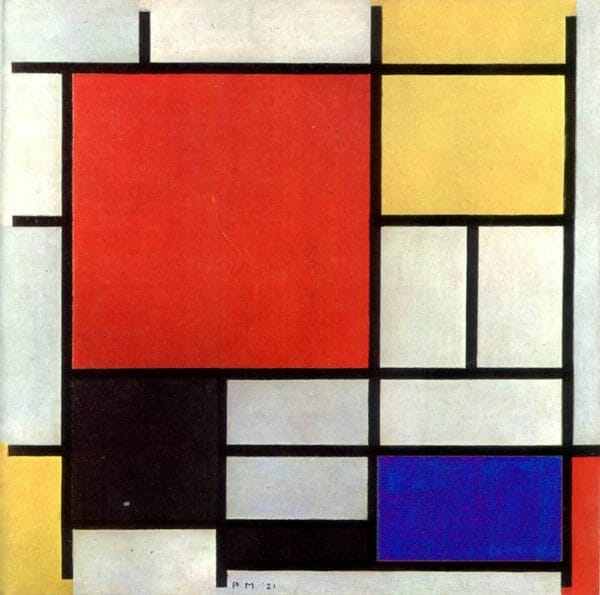

This abstraction and manifestation of inner reality was the stated aim of the founding abstract artists of the twentieth century, foremost among them being Constantin Brancusi (1826-1957), the founder of abstract sculpture, and Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944), the founder of nonfigurative abstract painting. Others could also be mentioned, such as Piet Mondrian (1872-1944), all of whose work was inspired by his belief that there was a spiritual way of understanding nature that was deeper than scientific, empirical knowledge. Like many of his time, he was much influenced by the theosophical movement, an esoteric salad of eastern philosophies and religions. Nevertheless, he was on a spiritual journey. The majority of our art historians’ books have, from embarrassment it seems, omitted the central role that spiritual quest played in early abstractionism. We may or may not like what these artists came up with, but it cannot be denied that what motivated them were consciously held spiritual aims. Novelty was not their object, but the embodiment of objective truths. It was not until the latter half of the twentieth century that novelty seems to have become an end in itself, the fad for “Shock of the New” as the late critic Robert Hughes dubbed the trend. When art loses its way, it loses it because it severs itself from its spiritual role, as a quest for God, a quest for a transfigured world, a quest for timeless truth in the midst of suffering.

Fig. 9. Wassily Kandinsky, St. George II, 1911.

Reverse glass painting, 11.8 × 5.9″.

The Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, Germany.

Fig. 10. Constantin Brancusi, Head of a Woman, 1918. Gouache on board laid down on canvas,

25 5/8 x 19¾ in.

Moreover, Hart also clarifies what is meant by the term “abstraction”:

We tend now to think of abstraction as a departure from reality. But most early abstractionists understood their venture in the literal and more original meaning of the word abstract, which is to draw out. True abstraction in art is to draw out and make hidden reality manifest in physical form.[v]

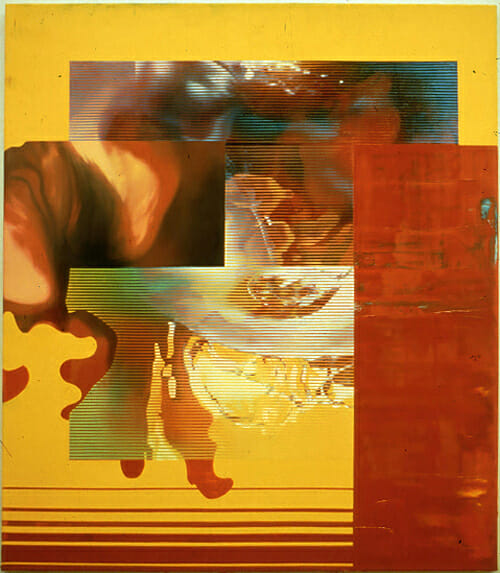

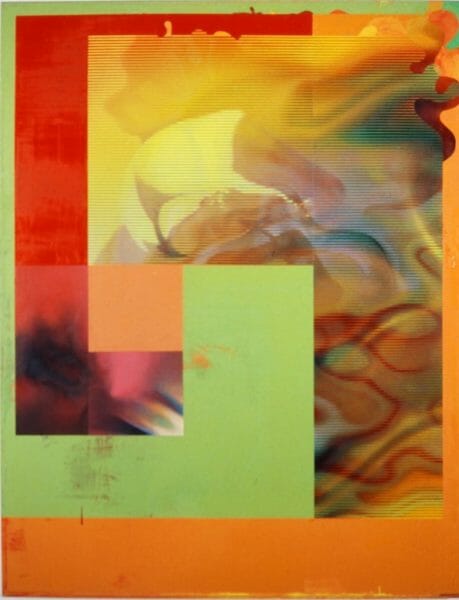

Fig 12. By author, Screen: Prelest, 1997. Oil on canvas, 48 x 48 in.

This is one of the Screen Paintings, a series that I was working on immediately prior to taking up iconography. Commenting on my work at the time the painter and art critic Gregory Amenoff wrote: “… his sources are found in the pixilated light of a monitor, the shiny gleam of advertising and the brave new world of pure abstraction. No room for the sublime vision here as languages collide in a violent interface that celebrates the denial of any one whole. His elements don’t dance – they shove, truncate and argue. His piece ‘Screen: Prelest’ is a perfect metaphor for our relentlessly active attentions.” Whether this is a good review or not depends on how you feel about postmodernism.

I completely agree with Hart on the point of convergence between the icon and Modern art’s aim in manifesting an inner reality by non-naturalistic pictorial means. However, I tend to be a bit more critical on the pioneers of abstraction and have expressed, in a previous article which goes into my involvement with abstract painting, an interpretation that is somewhat negative, focusing mainly on the dualist and dis-incarnational implications of their work; tendencies which of course reflect their lack of ecclesial grounding. Nevertheless, I still appreciate their work as an aspiration towards the divine and I’m grateful to them as partly responsible in preparing my way and leading me to the practice of icon painting. Anyhow, I just mention this as a way of pointing to the complexity of the matter. Be that as it may, depending on the issue at hand and the angle through which we’re analyzing Modern art, the glass could be perceived as either halfway empty or halfway full. Regardless, modernism does not cease to be a malaise, and today’s abstract painting has mostly, if not completely, lost its metaphysical aims. It gradually became formalistic aestheticism and hence purely “sensational,” and now, with the onset of postmodernism, cynical, ironic and self-referential pastiche. From the lofty attempt at manifesting the Real, it has now sunk into the banality of reveling under the spell of the alluring seductions of simulacra. Just take a look at the samples of my own abstract paintings (Fig.12-16) and you’ll understand what I mean. But this is hardly surprising, as it’s only the fruits of “art for art’s sake.”

Therefore, this is why I do not hesitate to both criticize modernism as a general ideological stance or set of assumptions, since in it we find, among other ills of our civilization, the seed of all the vacuous decadence which passes today by the name of “art”; and yet, at the same time, quote or speak positively of some modern painters, whenever they helpfully expound on pictorial facts and practical issues of painting, or exhibit a yearning for the Sacred and Tradition. It’s all about nuance. Sometimes it’s not a question of either/or but one of both/and. So I think this sufficiently shows that I’m not just “speaking from both sides of my mouth.”

Fig. 17. Fr. Silouan Justiniano, Holy Wonderworker and Unmercenary Physician Damian, 2016. Egg tempera and gold on gessoed panel, 8 x 10 in.

Pseudo-Traditionalism

As I constantly reiterate, icon painting is not an ossified specimen of the past, it’s a living art, and as such in constant interaction with its historical context, whether we accept this fact or not. Yet, the painter should proceed in this dynamic without, in fickleness, falling prey to the allure of temporal fluctuations in an attempt to “keep up with the times.” Herein lies the challenge. Icon painting has to be engaged creatively if it is to escape the simplistic pseudo- traditionalist misconception which thinks of its form as completely unchangeable for it to be legitimate. Stagnation leads to death. Tradition flows. Tradition presupposes creativity. This point cannot be overstated. Yes, there is a timelessness in the icon, mainly its principles, whether theologically or pictorially speaking, but there are aspects that are also very time specific. This is the paradox. So today contemporary icons can hardly avoid taking into account the history of 20th century art. The icon painter can glean from it whatever is in conformity with Tradition, just as the iconographers of late antiquity gleaned from the Greco-Roman world its painting conventions and mythological motifs and transfigured them. So, were they modernists in doing so? Speaking with both sides of their mouth, one pagan the other Christian? Yes, the letter is to be revered and respected, but not at the expense of the spirit of Tradition. We’re not interested in turning back the clock in romantic and utopic nostalgia for the Middle Ages. The point is to tap into the Source they tapped into and enabled them to produce the great monuments and artifacts we now hold in museums and revere, meanwhile being too blind to see that they stare back at us accusing our own cultural decadence. In differentiating Tradition from “traditionalism,” which I think is more accurate to call “pseudo-traditionalism,” Cornelia A. Tsakiridou says:

Tradition may thus be likened to a flowing river in which different forms of life arise and to which they belong collectively while retaining their uniqueness and distinctive forms. Unlike traditionalism, it is a witness to its own emergence, rather than a dictating, regulating matrix of expression ‒ hence its inherent freedom. Immersed in this river of grace the artist is not asserting a self-originating, self-centered vision. Rather, he emerges as the unique carrier of a dynamic trajectory of charistmatic energy and vitality that actualizes yet unformed possibilities inherent in the art, ideas, literature and music of a past that opens its full life to the present. Here historicism becomes irrelevant because the now and the forever, the nun and aei, converge.[vi]

The danger is that this nuanced approach is susceptible to misinterpretation. The so called “traditionalist” (conservative) will think I’m being a modernist in pursuit of “self-expression” in defiance of so called “canons,” while the modernist (liberal) will think I’m just condoning the hankering after “novelty,” “innovation” for its own sake ‒ the subjugating of the icon to a constant “updating” according to the zeitgeist. Both are missing the point. They forget that Tradition both transcends time and is to be found here and now. Both are failing to discern the principles of Tradition, which are to be found, by those who have eyes to see, in the mean between extremes and present in the most unexpected places, even in Modern art. Therefore, let’s not forget that the iconographer as the, “…scribe instructed concerning the kingdom of heaven…brings out of his treasure things new and old.”

Notes:

[i] A.K. Coomaraswamy, Why Exhibit Works of Art, http://www.studiesincomparativereligion.com/public/articles/Why_Exhibit_Works_of_Art-by_Ananda_Coomaraswamy.aspx (accessed, July 20, 2017).

[ii] Brian Keeble, “Of Art and Skill,” Sacred Web: A Journal of Tradition and Modernity, Vol. 17, Summer 2016, pp. 23-33.

[iii] As Keeble notes, “Plato, in stating in the Gorgias that he could not fairly give the name ‘art’ to anything irrational, was no more than restating a teaching of Pythagoras who is said to have taught that ‘art’ is a habit of co-operating with reason. Aristotle, in his Nichomachean Ethics, extended the same line of thought in teaching that ‘art’ is the capacity to make, involving a true course of reason. This doctrine makes clear that the creative principle that is art is a rational habit or disposition of the mind to pursue a true course of action in making something. Thus art stays inside the artist, being understood in terms of the imposition of form upon substance or matter – sound if he is composer, stone if a mason, and so on. But at the higher level it was understood as an analogue of a cosmic principle, whereby the Logos, the Divine Reason, manifests itself in the world of created things.” ibid. The icon arises from this traditional understanding of art as skill. But it should be understood that the emphasis placed on “reason” in this doctrine of art is not to be confused with “rationalism.” In this context it presupposes man as higher than irrational creatures and therefore logikos (rational), which in the platonic and patristic sense includes both nous (man’s highest faculty) and dianoia (discursive reason). Hence here Keeble is not merely upholding the kind of “rationalism” as an end in itself that Joseph Chiari (note iv) sees as symptomatic of the modernist mentality.

[iv] Joseph Chiari, The Aesthetics of Modernism, Vision Press Limited, London, 1970, p. 9.

[v] Aidan Hart, Holy Icons in Today’s World: A Living Tradition’s Insights Into Contemporary Issues in Modern Art, Ecology and Community. A talk given in Austin, Texas, December 12th, 2013, at St John the Forerunner Orthodox Parish. https://aidanharticons.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Austin-Icons-in-Modern-World-1.pdf (accessed July 20, 2017).

[vi] Cornelia A. Tsakiridou, Icons in Time, Persons in Eternity: Orthodox Theology and the Aesthetics of the Christian Image, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2013.

A very nuanced & balanced approach, Fr. Silouan! Hopefully, your clarifications & qualifications are beneficial.

Some of the work put forward on the OAJ in the last two years has probably stretched the readership’s tolerance for what an icon can look like and still be an icon. I personally have a few times here been uncertain what is being put forward as iconography, vs. what is art that happens to share a lot of aspects of iconography. I think what many of us are hungering for visually (if that even makes any sense) is an iconography that is fresh, but that we can also trust. I don’t want to invest hours and months of my life in prayer in front of an image that irks my my aesthetic sensibilities, nor that is aesthetically perfect but stale. I want the icons I pray in front of to be nourishing on many fronts, aesthetic and pastoral.

There is a certain mode of detached appreciation one has to enter into to engage with works of art that are not immediately accessible. This happens to me a lot when I go to a museum, and it puts me in a certain ‘heady’ mood that feels cool I guess but is not really grounded. It’s a different mode of engagement with the visual world than I want icons to have. If possible, I want them to run out and embrace the viewer like the father of the prodigal would.

I say all this to give some credence to people’s knee-jerk reaction if they don’t like an icon. This is an important experience. It may not be the final one, but it is important. If we ignore the instinctual first impressions made by our icons or our works of art, and ask the viewer to enter a heady space of appreciation in order to engage, I’m cautious of doing that. True, icons can be an acquired taste, and true they can take a long time investment to get the most meaningful nourishment from. I just want the first impression and aesthetic jolt to be used positively by iconographers, not ignored and left to chance. These are not fully formed thoughts, so I’m hoping you’ll correct me, Fr. Silouan.

Anyway, I have one more thing to add. When we speak of what is traditional or not in terms of icon painting or the icon itself, let us always include in the conversation that iconographers need to submit themselves to their fellows. Our church requires all Christians to confess their sins and live in obedience (even bishops do this). So as we are in an era of recovering a culture of icon-making, let all iconographers submit to one another. This is going to look different for each person, but it means 1.) see yourself as a lifelong learner, always improving, and 2.) surround yourself with enough people who will provide blunt constructive criticism to keep you from growing stale. If you are married, ask your wife or husband what they really think of that face – does St. John look grumpy or does St. Mary look doped? If you are a monk, in addition to your superior, ask visitors to the monastery what they think – is this pink just too much, do you see anything that is confusing or looks anatomically off? We all probably have friends who are graphic designers or painters or art teachers – they have trained eyes and their impressions of the work will enrich it. My point is there is no such thing as traditional icon painting if we are all self-taught. There is no ‘river’ without being jostled by the waves made by those around us and upstream from us. Let us not suffer the fate of the emperor whose new clothes needed to be pointed out by a child before he realized he was naked. The point has probably been made better by others elsewhere, but I am reminding us here.

I understand what you mean, Baker.

Yes, it could be said that OAJ has put forward some icon painting that perhaps pushes the envelope too much. But I don’t think we have gone overboard. Its healthy to be challenged from time to time. The point in doing so is actually to help awaken us from the stupor of taking what a traditional icon is “supposed” to look like for granted.

I agree completely, many of us are hungering for trustworthy fresh rather than stale icons. I also agree that an icon should be “nourishing on many fronts, aesthetic and pastoral.” But, we’re not going to find the balance until we first wake up and begin to take the time to look closely, slowly and honestly, with discernment, at the pictorial reality in front of us.

Furthermore, perhaps many intuit the staleness and lack of genuineness, but are too afraid of saying anything — thinking that doing so would be irreverent — since they’ve been told repeatedly: “An icon is not ‘art’.” Unfortunately, the icon is often looked at through a screen of assumptions that, more often than not, tend to bypass and ignore its pictorial reality. I don’t believe we’re going to get anywhere until we begin to see that the icon is indeed a work of art, albeit liturgical and not merely autonomous. It presupposes creative, interpretive engagement and skill, as is clearly evident in its long history of stylistic variation within the matrix of Tradition. Anyhow, indeed, as you point out, participation within Tradition presupposes our work being honestly critiqued and vetted by the community of the faithful.

Indeed, Fr. Silouan, indeed.

We must always remember that we live within a living Tradition. The Holy Spirit works within modernity, and I, for one, find that many of the “modern” icons (and what are we saying when we use that phrase anyway? It just means that a modern, twenty-first-century iconographer/artist is writing/painting it) call me to worship in fresh ways and speak to my soul in the century in which I live. I find that in many issues within Orthodoxy, critiques (which can be helpful) often evolve into unhealthy criticism and judgment (not helpful). I would imagine that anyone who sets out to write an icon does so from a spirit of humility and worship. I am so happy to leave the Holy Spirit free to do and be what the Holy Spirit is in all times, especially in these matters. This allows us to take the gold that is there while leaving slavery (to legalisms, perhaps) behind.

In any icon , we can judge the balance of three essential elements: the theology of the image, the beauty of the image, and the integrity of the semantic language of the icon. This last aspect was created to show invisible truths impossible to express through any other artistic means. Forgive me for being pedantic, but this essential semantic dimension includes the proper use of explicit symbols (like the stars on the Mother of God’s garments) or by implicit means (how an icon uses light to create form, opening form in inverse perspective, the codification of colors, etc.). The way all forms are illuminated and opened up in inverse perspective create the overall appearance of the icon, from inside. Most self-consciously made modern icons pay little attention to this aspect, which compromises the integrity of the icon. This is because the semantic language is either rejected, or not understood, or worse, it is mistaken as simply the overall style of an icon. Without the traditional semantic aspect- the grammar of the icon- iconography becomes just another style of religious art, and if that’s all it is, then any style is as good as any other- simply a matter of taste. Even though there are many styles inside of iconography (historical, geographic, ethnic) icons are not simply a style of religious art, they are a singular vision of reality that shows the integration of material and spiritual worlds. To reveal it, it uses an absolutely unique, traditional artistic language which evolved over centuries, from the experience of our inspired ancestors, smarter and holier than ourselves. Why modernist aesthetics fail iconography is that modernism is not about harmony, but fracturing and dissonance. Modernism can express today and tomorrow, but not the whole space of eternal time, which also includes yesterday. Most modernist painters were influenced by icons, for better or worse, but they only looked at the aesthetic aspects, which they saw as distortion. They secularized the icon. It seems a contradiction to re-incorporate all that back into an icon. I thought an icon was an antidote for the ugliness and disorder of our world. I thought the icon was relief from the brutality and incomprehensibility of contemporary art. I can see that the incorporation of modernism is a refutation of hyper-nostalgic iconography, and our lack of an indigenous way, but we can’t move forward, or create a modern form of iconography, without a solid foundation in its traditional grammar. Which I don’t see. Which in America, is rare in any aspect of our culture. Our lingering in traditional forms of iconography is provisional, but essential, or its future will not be a stable tradition. How it will evolve from there is the work of our successors.

Thanks for your lucid comment, Marek, it clarifies a lot. Let me just try to clarify my position a bit in light of you thoughts.

When I speak in general of “traditional principles” I have in mind the synthesis of the three elements you enumerate. And when I speak, more specifically, of the icon’s “pictorial principles” I also have in mind what you refer to as the “semantic language” of the icon.

Indeed, the “semantic language” is extremely crucial, since it’s not merely an arbitrary component, just relegated to “taste.” But, I would add that it’s stability, or perceived “changelessness,” is contingent on it being a lucid conveyor of the truly immutable Tradition. Hence, there is always the possibility that it will change whenever necessary, as to better meet it’s function as conveyor.

For, example, the Church has the authority to alter its linguistic theological formulations in its fight against heresy. The Mystery of the Faith remains the same but the formulations are provisional. So the formulations of the Ecumenical Councils are acknowledged as authoritative, not just because they were agreed upon in council, but rather because they communicate the Truth the most lucidly as to meet the need of “fencing” the Mystery in order to ward off the falsehood of heresy. Nevertheless, they do not exhaust all other possible formulations. If the Church deems it necessary the formulations can also be altered to meet the pastoral need. So the Mystery of the Faith remains the same, immutable, but the “mode of expression” used to communicate its inexhaustible fullness is not to be considered as completely frozen. I believe the same applies to the icon’s “semantic language.”

Moreover, as you noted, even when the traditional “semantic language” is used we still see the variation of “dialects,” which attests to the “diversity in unity” of ecclesial life. The “sematic language” ties the dielects together without smothering and stifling them. This is what I have been mainly focusing on in my posts, the acknowledgment of this reality, not the promotion of the willful alteration of the “semantic language” under the pretext that the “Spirit blows where it wills.” This, I believe, is where the iconographer has the most flexibility — in the possibility of speaking his own dialect.

Not to digress, but I think a legitimate question to keep in mind is: do we at times take the “dialect” to be the “semantic language” proper?

In any case, I agree wholeheartedly that, “Most self-consciously made modern icons pay little attention to” the “sematic language” and that therefore this “compromises the integrity of the icon.” This is the last thing I want to come off as encouraging. And, without a doubt, I’m with you in stressing that, “icons are not simply a style of religious art, they are a singular vision of reality that shows the integration of material and spiritual worlds,” which is conveyed by it’s traditional “semantic language.”

Your reading on the modernist coopting of the icon is generally speaking spot on. Nevertheless, we should not dismiss that some good did come out of it, in particular how it paradoxically contributed to the icon painting revival. I also agree that “the icon” is a “relief from the brutality and incomprehensibility of contemporary art…” And, yes, it is crucial that the traditional “semantic language” is first laid as a solid foundation… But, I also think that there are contemporary developments taking place right now that demonstrate balance and discernment, although they might at first seem a little odd. So, yes, the “successors” will indeed come with interesting and healthy developments, but it seems to me that some of them are in fact already here with us today, speaking beautiful dialects.

Thanks again Marek for your lucid thoughts.

I dont think the whole issue of a double standard is being addressesd because the core of these articles are assertions basically replacing faith with aesthetics and that is a personal choice. One might argue that this is indeed a historic inevitability one at the core of the problem, one that all artists face at this juncture in history. Have aesthetics replaced function.

I think it would be fruitful to concentrate on other aspects of iconography as sometimes happens in these pages; for instance, the tradition of copying that links iconography with other great traditions, method, process, personal evolution, prayer. Also, the issues that both contemporary art and icons share in the struggle for validity is of the utmost importance. Triumphantly bashing contemporary art; what a bore! People who do this do so at the risk of sounding provincial and uninformed, and honestly most respondees to this site sound pretty intelligent to me.

One more thought – the ikonostasis at the Synod on Park Avenue in NYC is modern, executed very traditionally. It is absolutely drop dead stunning (imho), and within the tradition of iconography the artist humbly evolved a linear quality and superb technique that is both personal and traditional albeit subtle!

The question isn’t about evolving traditions it is about time, time, time selfless commitment and prayer.

Recomendation:

The End of the History of Art,

By Hans Belting

… brilliantly tackles many issues touched upon in FSJ’s essays . Just finishing library copy and ordering my own.