Similar Posts

A New Icon of St. Mary of Egypt and St. Zosimas

Notes on Form & Symbolism

By

Fr. Silouan Justiniano

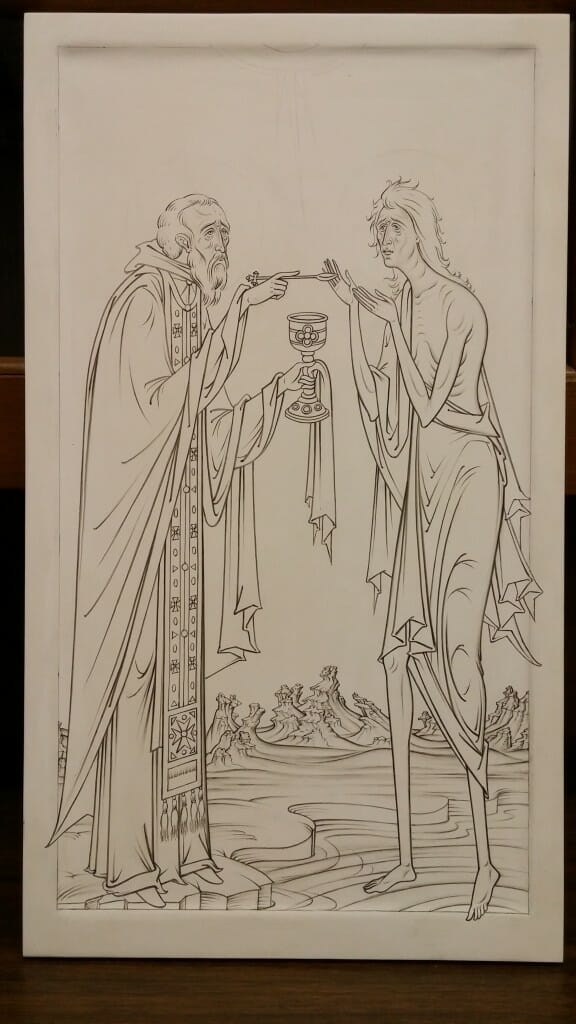

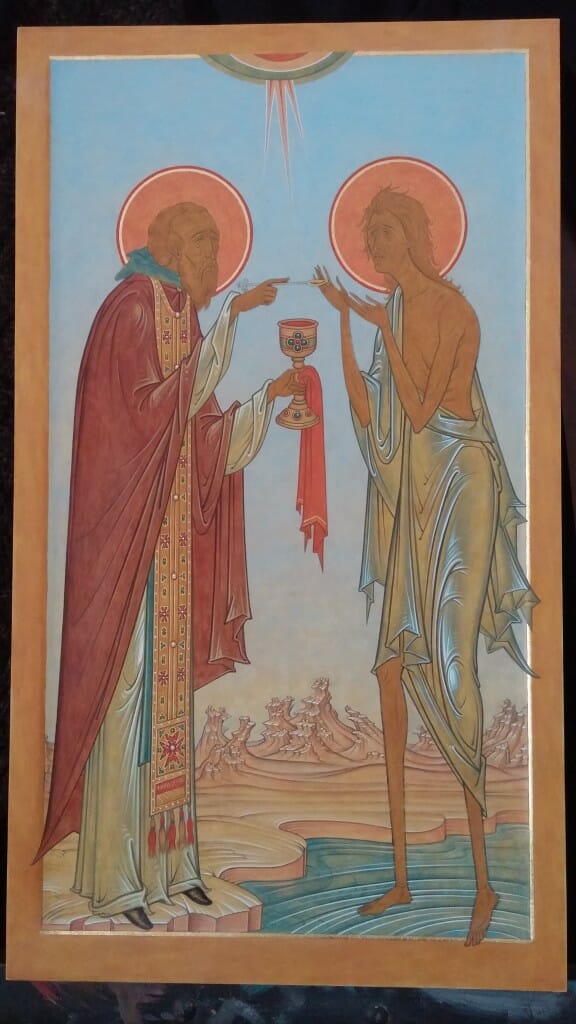

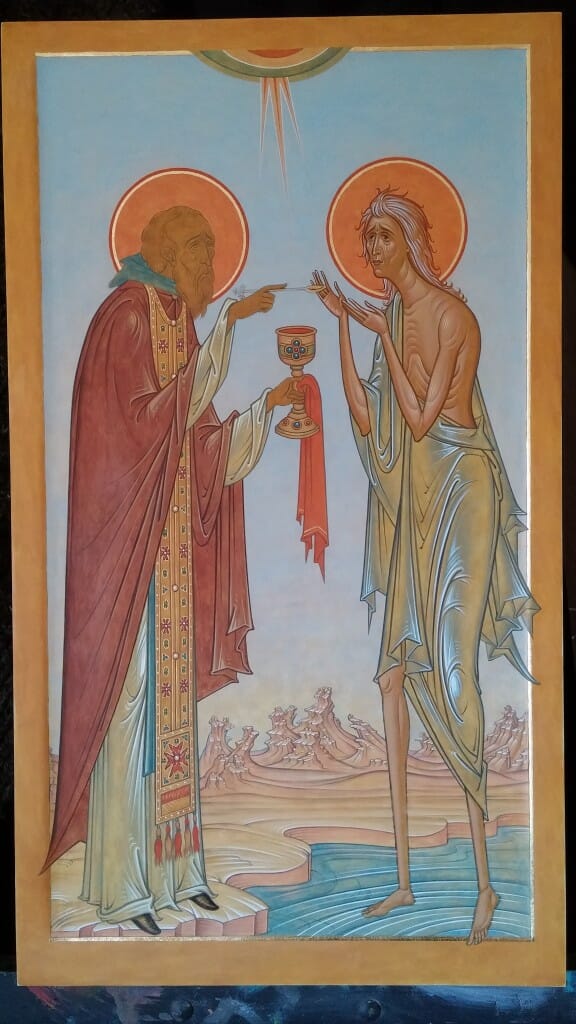

St. Mary of Egypt receiving the Holy Eucharist from St. Zosimas by Fr. Silouan Justiniano. Egg tempera on wood, 10 7/8 in. x 19 in.

In thee, O Mother, was exactly preserved what was according to the divine image. For thou didst take the cross and follow Christ, and by thy life, didst teach us to ignore the flesh, since it is transitory, but to care for the soul since it is immortal. Wherefore O our righteous mother Mary, thy spirit rejoices with the angels.

Troparion, Tone 8

Believe it or not Great Lent is almost over and the 5th Sunday of the Fast, which commemorates St. Mary of Egypt, is just around the corner. It goes without saying that in many ways this Fast has been difficult. Yet, without a doubt, with the struggle have come many blessings, not the least of which was completing an icon of St. Mary of Egypt for Holy Ascension Orthodox Church in Mt. Pleasant, SC. I was fortunate not only to have been given the honor of painting the icon, but of also to have great freedom in the conception of the composition. So I gladly took the opportunity to interpret the usual prototype which depicts her receiving communion. The icon conflates two episodes of her life: St. Zosimas, who discovered St. Mary, imparting to her the Holy Mysteries, and her walking across the waters of the Jordan. In what follows I’ll be highlighting some formal and symbolic features worthy of consideration.

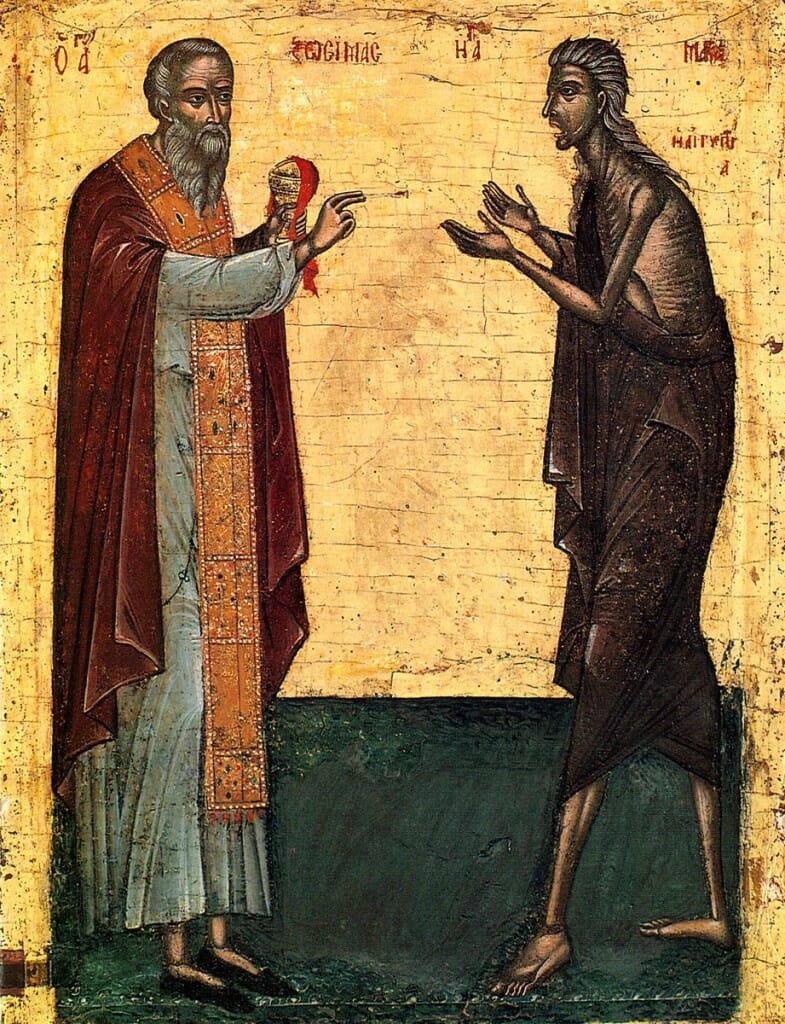

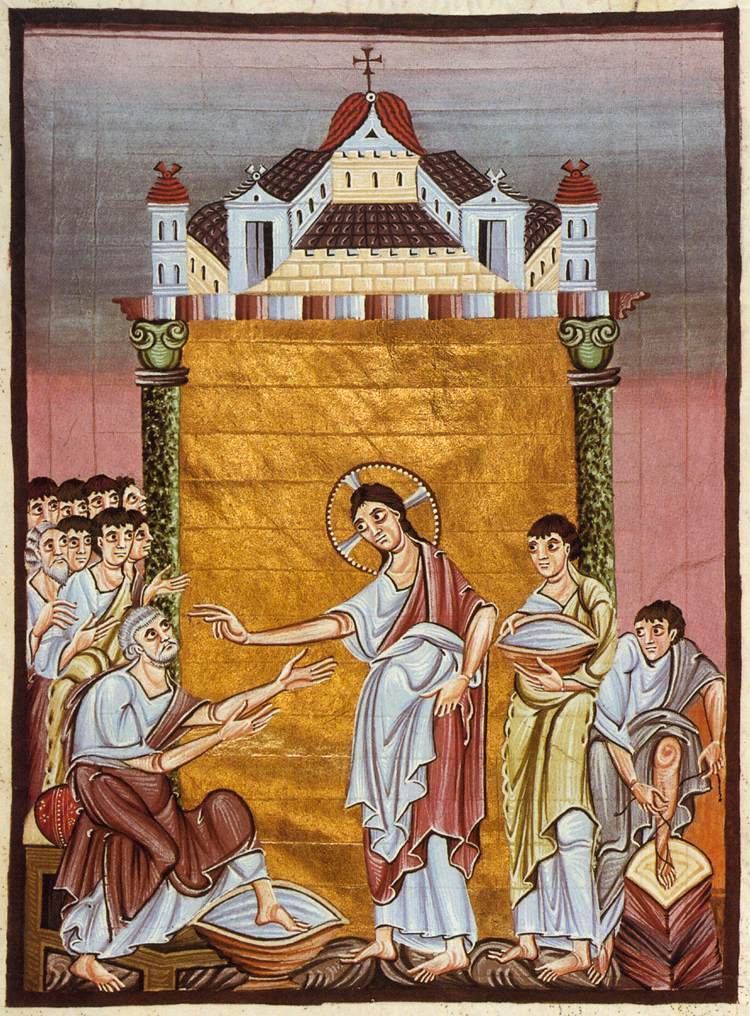

St. Mary of Egypt communing the Holy Mysteries from St. Zosimas. Icon of 16th cent. Monastery of Rousanno Meteora Greece.

As will be readily noticed, liberty was taken to incorporate a gradated background into the composition, which according to some schools of thought should not be done in traditional icons. Indeed, there are hardly any precedents of the device in medieval Byzantine icons, although we do find some Ottonian manuscript illuminations that implement the device successfully. The 19th century Mstera masters are the main ones that come to mind as the exponents of the device in recent history.[i] However, in most cases in Mstera icons the backgrounds are painted with a dark horizon with the upper zone of a lighter tone, the reverse of what is customary in depicting skies. In this way it is implied that a Heavenly radiance is descending on the subject. Mstera icons can perhaps be seen as an attempt at synthesizing both the best features of traditional iconography and Romantic landscape painting. From the former, hieratic frontality and abstraction; from the latter, ambiguous atmosphere and landscape details. Both of these elements come together to evoke the theme of the Sublime.[ii] Hence it could be said that Mstera icons fall into the category of iconographic Romanticism, but not in the derogatory sense of the term commonly applied to some 19th century realist painting.[iii]

Caspar David Friedrich, Monk by the Sea, c. 1808–1810, oil on canvas. In this painting we find a classic example of the exploration of the aesthetic category of the Sublime in 19th century Romanticism. As the minuscule figure of the lonesome monk on the bottom left suggests, the quality of the Sublime involves an awe inspiring and acute awareness of our seeming insignificance as we encounter the power and immeasurability of Nature. It therefore leads to pondering on that which surpasses the senses and comprehension and can even induce dread or terror. It thus involve the apprehension of the numinous, that is, Nature as theophany.

Caspar David Friedrich, Wonderer Above the Sea of Fog, c.1818. Oil on canvas

37.3 in × 29.4 in.

Kunsthalle Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany.

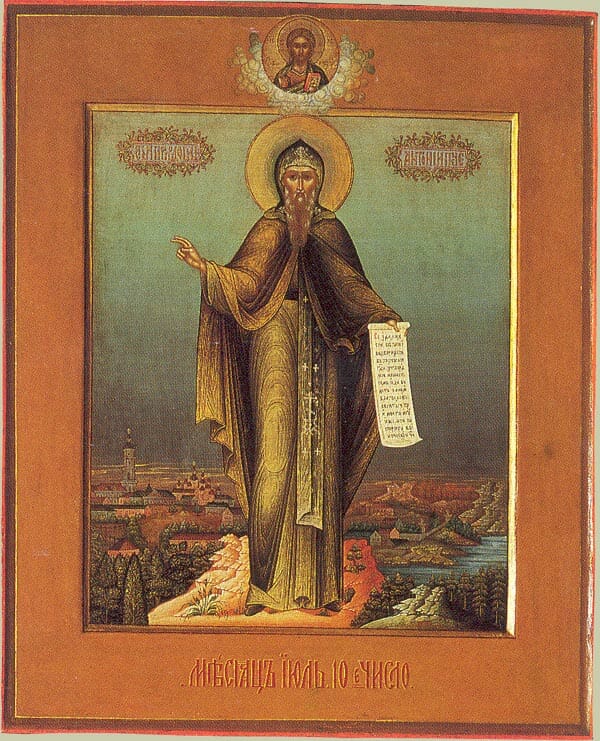

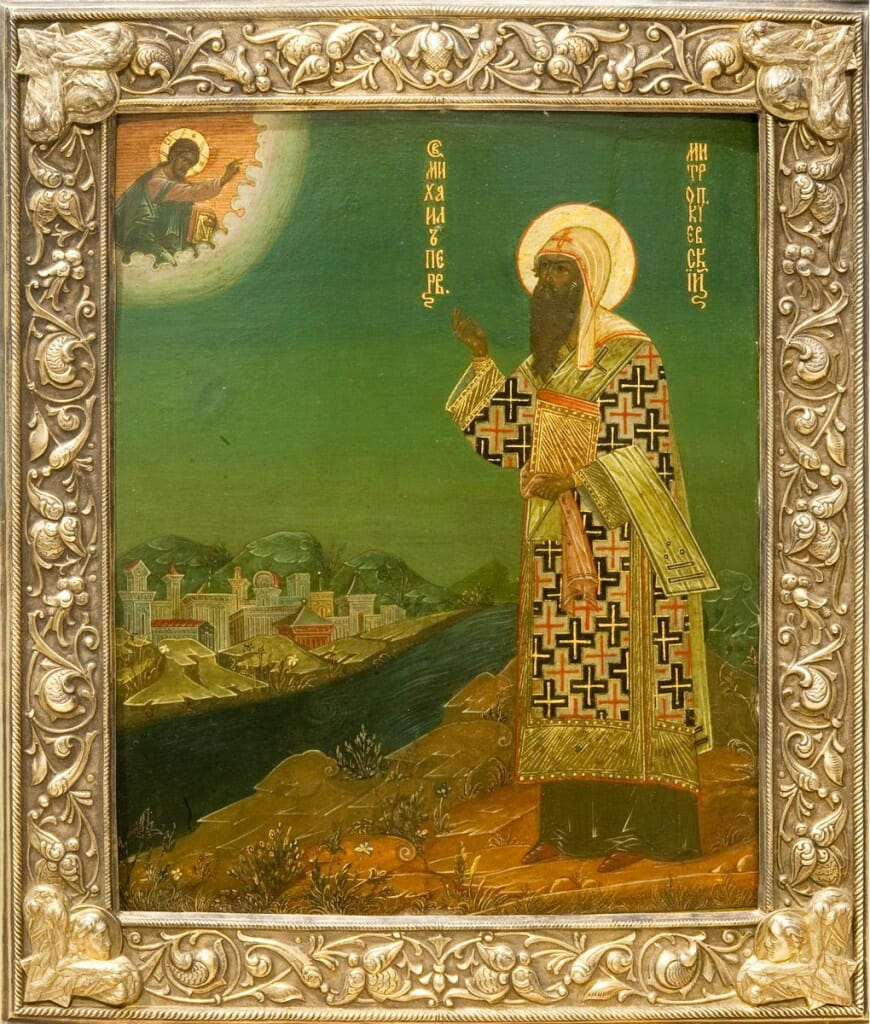

St. Peter Metropolitan Moscow and Wonderworker, by Mikhail Dikaryov, 1901. An exquisite example of the work of arguably one of the most renown representatives of the Mstera style working in Moscow at the turn of the 20th century.

Venerable Anthony of the Caves, by by Mikhail Dikaryov, c. late 19th – early 20th cent. The State Hermitage Museum. Without a doubt, the primary focus of C. D. Friedrich’s Romantic work is the contemplation of Nature. The figures tend to become secondary in importance as they turn their backs to the viewer, as if inviting us to join them in pondering the awesome scene. However, the grandeur remains outside of those who behold it. The contemplation remains aesthetic, impersonal. Conversely, in Mstera icons we encounter the saint face to face, or we join him as he encounters Christ in noetic vision (see below). The focus is on prayerful personal communion and the contemplation of the saint as an embodiment of virtue. The landscape elements help to create a mysterious mood in the scene but remain secondary. Hence, in this context the expanses of ethereal space or “sky” connote not only the numinous in Nature, outside ourselves, but also the otherworldly inner life of the saint. The outer and inner symbolically converge, nobility of soul, sanctity, is brought forth as another dimension of the Sublime and we are invited to participate in it through prayer, face to face.

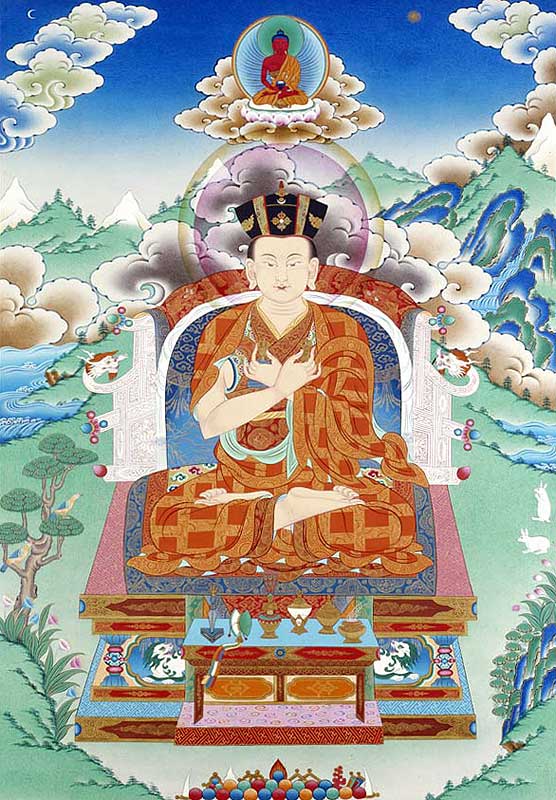

Be that as it may, although outside the confines of Orthodox iconography, Thangka paintings also come to mind as an example of non-illusionistic gradated backgrounds in a sacred art that parallels the icon in many ways. In other words, as can also be seen in the Ottonian illuminations, the gradated background need not be solely identified with naturalistic painting. So although there are not many examples of this devise in icons that would lead us to justify the practice whole sale, or put it on the same level of gold, a flat, neutral or colored background, nevertheless it has a potential worth cautious and discerning exploration. Although not to be considered first in the hierarchy of iconographic devices within the tradition it would be unwise to completely abandon its pictorial virtues.

Contemporary Thangka of Buddha-Shakyamuni. Notice the transition from dark blue, to light blue, to yellow, in the depiction of the sky. Although we are clearly meant to read the background as a “sky”, nevertheless, the way it is handled overcomes mere naturalism in this context. Also notice the use of gradation in the depiction of the hills, a device also found in icons.

In this Thangka we find pictorial devices that parallel the icons shown above, such as the use of ethereal gradation, hieratic frontality and flat geometric patterning, all of which contribute to instill the image with a sense of the timeless and devotional. It could be said that this image is in some ways much more abstract than the icons, almost appearing to materialize out of mist and light. Yet, it is clear that both the icons and this Thanka take the device of gradated backgrounds to a non-naturalistic direction that is quite distinct from the examples of Romantic paintings shown above. This is even more so in the case of the Ottonian works shown below.

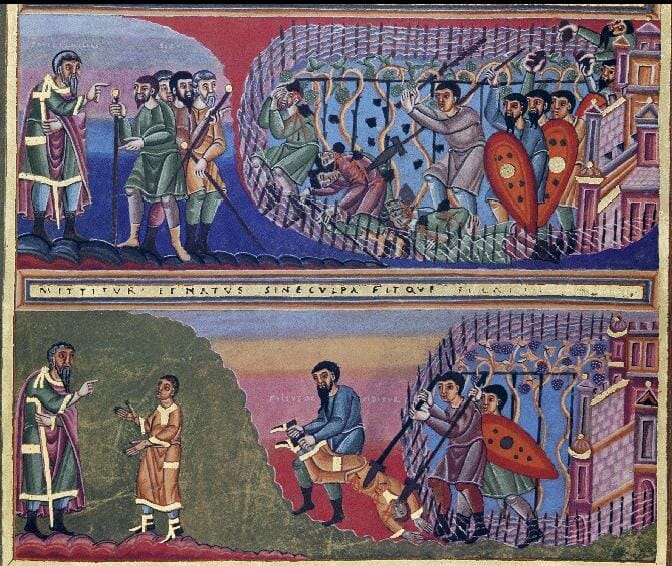

Vineyard Owner and Laborers (Parable of the Vineyard Owner), Codex Aureus Epternacensis, c. 11th cent.

The apprehension towards such a device is understandable given the profusion of its use, or rather misuse, in the worst of sentimental religious art and kitsch. There is no doubt that in most saccharin paintings attempting to induce “spiritual” feeling an atmospheric and ethereal device will be part of the tool box of effects. But my sense is that in an icon the gradated background device is not erroneous in principle, it is only a question of how it is implemented. If used successfully its symbolic potential within iconography can in fact be revalorized. It is largely a matter of context, whether or not it can help to amplify the symbolic import of the work at hand. In the case of our icon of St. Mary of Egypt this was indeed the case. If the sky in nature, with its multifarious colors, is a symbol of the Infinite and Undetermined godhead, immutable Beauty and Heaven, why not use the symbol God Himself has given us in an icon? As the Psalmist says, “The heavens declare the glory of God” (Ps. 19:1).

St. James and St. John with the Theotokos Enthroned. Contemporary icon by Anchimandrite Zenon (Theodor).

In the Liturgy incense smoke softens the denseness of our surroundings, yet it also reflects and thereby “materializes” light, it is a reminder not only of prayers ascending heavenwards but also of the divine glory and presence. It manifests the unseen, makes visible the invisible. Likewise, the somewhat smoky and atmospheric background in this icon can be said to have the same symbolic function, its luminescence being more a materialization of light through color than an attempt at illusionism. There is enough of an emphasis on the background as an abstract “color field,” with nuances of application, pigment sedimentation and transparency of material, that it becomes more than merely naturalistic. In other words, the background can be said to signify a “sky” as much as it “presents” its inherent pictorial properties as color sensation. In a way it imparts its own light. As Hans Hoffman would say, “In nature, light creates color; in painting color creates light.”[iv] Moreover, the very low horizon, centrality of the symmetrically arranged figures, the strong use of verticality and the increase of flatness at the top as compared to the bottom of the composition, helps to bring the eye back to the picture plane, it doesn’t get lost in the connotation of an ever receding illusionist background. Finally, the figure-ground “push and pull”, or flatness and depth tension, keeps everything in an equilibrium. By these formal means I believe the background is kept from becoming a sentimental cliché as would at first be expected. Let us now turn to and expand on some aspects of symbolism.

Through the use of subtle tonalities of light ochre and pink the desert appears to be more a habitation of sweetness and solace than a place of harshness and desolation, reminding us that, “They that sow in tears shall reap in rejoicing” (Ps. 126:5). The moment of the encounter can be said to be taking place in the morning, the golden horizon being symbolic of the arising of the Sun of Righteousness within the heart – the “city” of the Lord – a time of renewal from the darkness of iniquity. As the Psalmist says, “In the morning I slew all the sinners of the land, utterly to destroy out of the city of the Lord all them that work iniquity” (Ps. 100:8). The sky is a gentle blue, evoking clarity, for “When the intellect [nous] has shed its fallen state and acquired the state of grace, then during prayer it will see its own nature like a sapphire or the color of heaven. In Scripture this is called the realm of God that was seen by the elders on Mount Sinai.”[v] And in Exodus we read, “Then Moses went up with Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, and seventy of the elders of Israel, and they saw the God of Israel; and under His feet there appeared to be a pavement of sapphire, as clear as the sky itself…” (Exod. 24: 9-10).

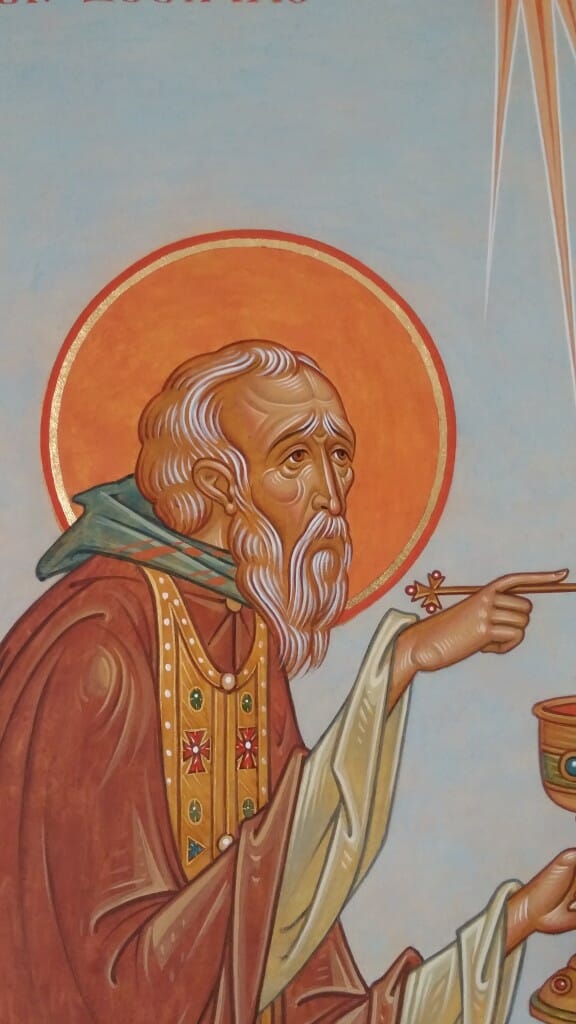

The composition is structured around the sign of the Cross. The vertical axis falls down the center from the triple radiance – symbolizing the Uncreated Energies of the Holy Trinity – and through the red communion cloth St. Zosimas holds, which reminds us of the precious Blood of the Saviour. The horizontal axis falls across the communion spoon connecting the two ascetics in communion. In the center, immediately below the horizontal axis and along the same level of the heart of the two saints, we find the Holy Chalice containing the medicine of immortality. Thus the icon emphasizes the Holy Eucharist – the Center of life in Christ – as the fruit of the Lord’s life-giving Sacrifice on the Cross, which brings about the perfection of agape amongst the faithful through participation in ineffable Communion between the Uncreated (vertical) and created (horizontal), the Immutable and mutable, God and man.

The halos, arranged symmetrically along the horizontal axis, form the base of a triangle with its upper point being the disk – a symbol of the presence of the divine Unity – cut off by the frame at the upper most part of the composition, which pictorially implies its extension beyond the confines of time and space. Through this subtle underlying geometry an upward thrust is introduced into the composition that complements the downward movement of the divine triple radiance. Hence the principle of “procession and reversion” is encapsulated geometrically. As the unerring beholder of noetic truth St. Dionysius says, “It is the Good…from which all things originate and are, as brought forth from an all-perfect cause; and in which all things are held together, as preserved and held fast in an all-powerful foundation; and to which all thigs are reverted as each to its own proper limit; and which all things desire” (DN IV. 4, 700AB).[vi] Likewise, “Every being is from the Beautiful and Good and in the Beautiful and Good and is reverted to the Beautiful and Good” (DN IV. 10, 705D).[vii]

The red communion cloth signifies that “the veil is taken away in Christ” (2 Cor. 3:16), that is, the “veil” of delusions arising from self-love are wiped away from the “eye of the heart” (nous), through the immaculate Body and precious Blood of the incarnate Logos. Thus, although in her former life St. Mary had never learned from books, through repentance her nous became so pure that as a mirror it reflected the words of Scripture which she could quote at will. Indeed, she “recollected” what had been inscribed therein from the beginning- the image of the Logos. For, “…the Logos of God which is alive and active, teaches a man knowledge” (Col. 3:16, 1 Thess. 2:13).[viii]

Exercising his priestly office, as if from an ambon, St. Zosimas stands firmly as a pillar on solid ground imparting the Holy Mysteries. Thus he symbolizes both at once stability and the active principle within the Church, the “pillar and ground of the Truth” (I Tim. 3:15) built on the Rock which is Christ (I Cor. 10:4), through which our participation in Uncreated Energy is actualized in the sacraments. The encounter between solid, dry land on which St. Zosimas stands and the waters of the Jordan also calls to mind the passage read in the rite of Holy Baptism: “Thou hast established the earth upon the waters” (Ps. 24:2; Office of Holy Baptism). That is, the Lord has establish the Church, His Body, in the unshakable stability of His divinity against the chaos, tumult and waves of corruptibility, worldly passions and the dragons, the demonic powers, that lurk therein.

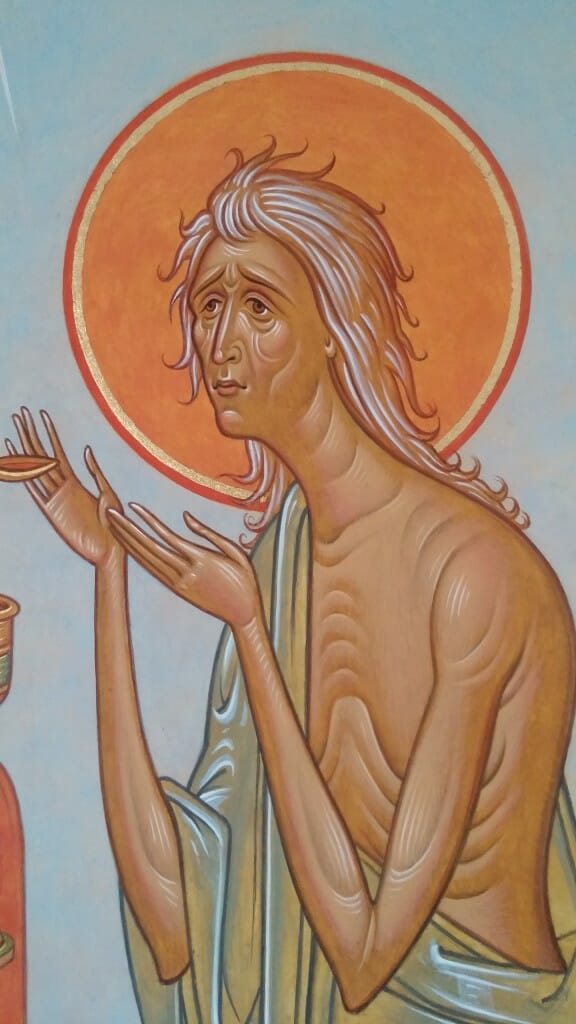

Complementing St. Zosimas, St. Mary as a communicant stands on the unstable waters of the Jordan. The Jordan as an image of Holy Baptism also signifies the formless primordial chaos, the materia prima, awaiting the fiat lux of the Spirit which hovered over it. Hence St. Mary in this context symbolizes the receptive principle within the Church, the members of the Body of the New Adam as “hyle” or malleable substance, to be formed and shaped by the Holy Spirit according to the divine Archetype. “All men are from the ground, for Adam was created from the earth…All His ways are according to His good pleasure. Like clay in a potter’s hand, thus men are in the hand of Him who made them, to render to them according to His judgement” (Sirach, 33: 10, 13).

St. Mary’s transfigured state, beyond the limitations of corporeality, is suggested not only by the fact that she walks on water, as the Lord Himself once did, but also by her luminescent yellow-green garment. Like precious gold, the yellow of the Sun of Righteousness glows within her, while green overshadows the glow as a symbol of the sanctifying power of the Holy Spirit, the “Giver of life.” Moreover, by standing on water St. Mary shows her overcoming of the turbidity and murkiness of the watery passions. Her mercuric state has been stabilized, lead has been turned into gold. In dispassion she becomes one with the One in Trinity and Trinity in Unity, her sins like drops of muddy water fall into the Abyss of mercy beyond being, causing a ripple without disturbance, dissolving without a trace, while her true self remains and arises undissolved. Solve et coagula…Through the furnace of repentance she has become an angel in the flesh.

She roamed in the desert naked feeling no shame for she regained the garment of her primordial beauty. In her former life she had an “insatiable desire and an irrepressible passion for lying in filth,”[ix] but she is now a symbol of the purified desiring aspect of the soul, the realization of true eros, “Oh taste and see that the Lord is good…who satisfies your desire with good things” (Psalm 34:8; 103:5). After 47 years spent in solitude she had one final and ultimate desire before departing this life: partaking of the Holy Mysteries. Indeed, her desire was fulfilled, for self-deification does not exist, asceticism and prayer are not enough, without partaking of the immaculate Body and precious Blood of the God-Man.

Notes:

[i] Yuri Bobrov tells us that in the room of Tsar Nicholas II, “There were 130 icons closely hung on the walls…like tapestry. This collection contained no ancient icons, revered by both scholars and collectors, but only contemporary ones made by expert icon painters such as Osip Chirikov, Vasili Gurianov, Mikhail Dikaryov and Alexander Cepkov. All were examples of the Mstera style where family workshops produced many thousands of icons firmly rooted in the stylistic traditions of the 17th century.” Y. Bobrov, “Late Icons as Symbols of Holy Russia: Icons in the Everyday Life of the Russian Royal Family,” http://www.templegallery.com/main.php?mode=6&p1=s07_bobrov, 1999 (accessed 10 April 2016).

[ii] As Robert Rosenblum notes, “Originating with Longinus, the Sublime was fervently explored in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries and recurs constantly in the esthetics of such writers as Burke, Reynolds, Kant, Diderot and Delacroix. For them and for their contemporaries, the Sublime provided a flexible semantic container for the murky Romantic experiences of awe, terror, boundlessness and divinity that began to rupture the decorous confines of earlier esthetic systems. As imprecise and irrational as the feelings it tried to name, the Sublime could be extended to art as well as nature. One of its major expressions, in fact, was the painting of sublime landscapes.” R. Rosenblum, “The Abstract Sublime,” http://www.artnews.com/2015/03/27/beyond-the-infinite-robert-rosenblum-on-sublime-contemporary-art-in-1961/, 2015 (accessed 8 April 2016).

[iii] When it comes to 19th century Realism, as exemplified by the works of Repin, Surikov and Vasnetsov, Yury Bobrov notes, “Realism as an art form, as well as, indeed, the realities of life itself, no longer satisfied the tastes of late 19th century Russian society. In many regards, the realistic style that had developed since the early 18th century was felt to be artistically and spiritually inadequate. The abstract paintings of Vassily Kandinsky and Orthodox icons may well stand in polar opposition, but relative to each other, they simultaneously became symbols of the age. The former were directed toward the future, the latter looked back to the past, thus reflecting the eternal duality of the Russian culture.” Y. Bobrov, op.cit.

[iv] Hans Hoffman, “Search for the Real and Other Essays”, in H. B. Chipp, Theories of Modern Art, Berkeley, Univessity of Chicago Press,1968, p. 543.

[v] Evagrios Pontikos, “Texts on Discrimination in respect of Passions and Thoughts,” in: The Philokalia: The Complete Text, St. Nikodimos of the Holy Mountain and St. Makarios of Corinth (ed.),G.E. E. Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware (trans.), Vol. I, London, Farber and Farber, 1981, p. 49.

[vi] As translated by E. Pearl in, Theophany: The Neoplatonic Philosophy of Dionysius the Areopagite, Albany, SUNY Press, 2007, p. 40.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] St. Sophronius, “Life of Our Holy Mother Mary of Egypt,” in St. Andrew of Crete, The Great Canon, Jordanville, St. Iov of Pochaev Press, 1967, p. 93.

[ix] Ibid., p. 87.

Fr Silouan, many thank for both the beautiful Icon and the article. Casper David Frederick is a particular favourite of mine as his art seems to communicate that element of ” otherness” or the Divine. Certainly the proposition you put forward of a tonal gradation in the background provides much food for thought particularly where the subject of the Icon is one where a gilded background would be “too much”.

May the Lotd continue to richly bless your ministry.

In Christ

Fr Paul

Fr. Paul,

Indeed, sometimes the gilded background can be “too much”. It is not uncommon to find garish gilding interfering with the painting passages and the icon’s overall harmony. So it goes without saying that the presence of gold does not guarantee the pictorial or theological efficacy of an icon. Also, nowadays we find “gilded” and shinny metallic surfaces everywhere. Hence, inevitably the look of a manufactured product enters into the way we look at an icon. Some gilded icons are so shiny that it makes you wonder if they are in fact meant to live up to the standard and compete with the “pristine” look of any other non-liturgical luxury product. So the irony is that under these circumstances gold runs the risk of being associated more with glitzy consumerism than Uncreated Light. Perhaps this is another example of how profane simulacra tends to insinuate itself in the realm of liturgical art.

In Christ,

Fr. Silouan

Having seen this icon personally (and having the great privilege of it being at my parish) I would like to say that its beauty and refinement is truly astonishing. It has a fineness and precision of detail that I have seen only in some aristocratic late-19th and early-20th century Russian icons. And yet it does not have the coldness one expects in such precise painting. It is as warm and alive as living flesh. A truly astounding feat of painting, by any measure! Someday, Fr. Silouan, it would be most interesting if you would speak of your techniques of craftsmanship, whereby you achieve this refinement and beauty of brushwork that looks so unlike anyone else’s work.

Thanks for your kind words Andrew. I will definitely work on getting something together that goes into the “techniques of craftsmanship” I rely on.

Thank you so much for this post. So very informative and beautiful.

Fr Silouan,

This is a breathtaking piece. I had just finished illustrating a half-traditional half-digital drawing for her feast day today and now that I saw yours I’m embarrassed to have even tried to illustrate it :O

Question though, in my illustration (https://www.instagram.com/p/BELvrL3TOcR/) I had placed Saint Mary on the left hand side contrary to how you and the typical Saint Zosimas and Saint Mary icons are arranged. Is there significance to having her on the right?

I think having St. Mary on the right makes more sense since we tend to look at images in our culture the way we read, from left to right. But it all depends on the narrative context and the restriction of the compositional format. In most cases the figure of most importance would either be in the center or towards the right, since the eye would automatically rest there, as if on the period of a sentence.

What a spiritually beautiful icon which blesses me even in the drawing.

The question here is which positons do the figures in the icon take? If we refer to the icon’s right, we see St. Zosimas. Suppose you were looking out from the icon where would your right be? If we are are looking at the icon from our point of view we would think that St. Mary is on the right. This arrangement with St. Zosiams on the right helps to draw us into and participate with the icon is part of the set of “canons” as part of the bookends of the tradition we follow.

Thank you, Father, so much for making this icon come into our world.

a sinner and a pilgrim, bess

This icon is so sincerely and beautiful it has caused me to question the notion of using graduated blues for the background. Finally my questions fell away. When I think of icons with mandorlas, the graduated blues in your icon seem to me to be like a mandola smoothed over the whole background. As you propose, the blues show the overarching presence of God.

[…] Zosimas and Mary by Father Silouan JustinianoAn article in yesterday’s Orthodox Arts Journal reveals a new icon of Saint Mary of Egypt—my patron saint—who is commemorated in the Orthodox […]