Similar Posts

An Icon of the Kingdom of God: The Integrated Expression of all the Liturgical Arts – Part 9: Linens

This is the ninth part of an ongoing serial (part 1, part 2, part 3, part 4, part 5, part 6, part 7, part 8)

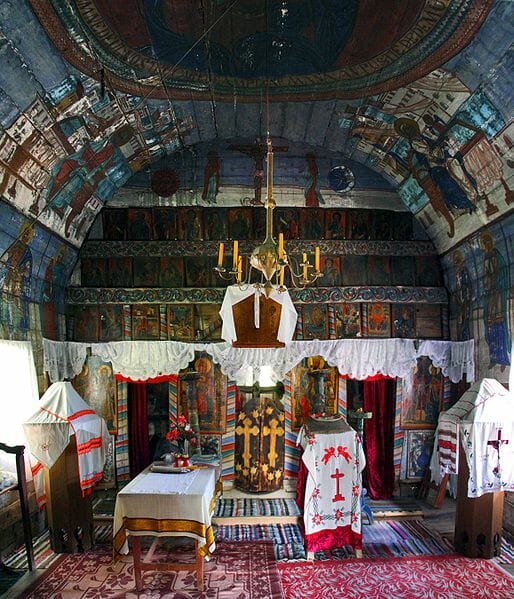

In Orthodox churches the use of white linens provides an avenue for textile work wholly different from that of silk vestments. Many nations have the tradition of honoring icons with sacred towels. These rushnyki are most often white with red woven or embroidered designs. They are a folk custom predating Christianity, and the embroidered designs are so old that their interpretation is frequently unknown to those who make them. Each region or village has certain traditional designs that have persisted for centuries or more. Some elements, such as stalks of wheat, have obvious meaning in a Christian context, but other motifs that persist from pagan times have no discernible meaning to their Christian weavers. As such, embroidered linens represent almost a polar opposite to iconography; they are a form of visual art in which representation and definitive meaning are unimportant.

Despite their adoption for liturgical use, embroidered linens are still towels that can be used for cleaning and drying in non-liturgical capacities. In village life they function as a sort of currency with social rather than monetary value. They are given away in great numbers at funerals and weddings, and a large collection represents a long life of family and friendships. In church, their functional use is as a liturgical towel for the priest to dry his hands on, or as a napkin during the ceremonial offering of bread to the bishop. But in village life they have another use as a way of showing honor. A visiting houseguest may be honored by having an embroidered towel draped over his shoulders. He becomes symbolically part of the family. In this capacity, towels have taken on a much larger role in church of showing honor to icons. In many village churches, it is considered important for every icon to be draped with a towel. It is the devotion of the village women to make these towels for the church and to keep them fresh and clean.

The tradition of rushnyki never assumed the pretenses of Neoclassical design. It remains a folk tradition, baptized by village women into the liturgical life of Orthodoxy with little notice or interference from men. But in a traditional Church they make a substantial visual impact. In their design and style, they are often the only work of art in a church that has the simplicity of folk art, and they are nearly the only thing present that is white in color. Through simple, anonymous devotion, they reveal the tireless work and unseen prayers of the pious women who are the backbone of every parish. Their rustic style and humble material show that it is not only wealthy patrons who adorn the house of the Lord. Indeed, the devotions of the poor and humble are worth more to God than all the riches of men, and so the rushnyki are placed closest to the saints of any gift to the church. A towel embraces the icon like a grandmother’s hug – a marvelous counterpoint to the lampada, which honors the icon with the more abstract gift of oil and flame.

Although rushnyki are a Slavic and Romanian folk tradition, the use of liturgical linens is universal. In Greek and Arab churches, comparable uses of linens appear in other forms. White lace is common in churches in all countries. It often ornaments the edges of white cloths used for all manner of decorative and functional purposes. Since Orthodox liturgy is served by male clergy, having linens, lace, and simple embroidery in the liturgical ornamentation adds a touch of feminine piety. The Orthodox in America should give more careful attention to this tradition. They are an indispensable element to the traditional furnishings of a church. They are not a mere ‘liturgical color’ brought out for some seasons as decoration, and put away for others. They are a tradition older and more universal than liturgical colors, and they should be always present in church like the pious women who weave them.

In America, women should learn to make their own versions of icon towels. It would be wise to adhere to the basic ‘look’ of Slavic rushnyki – mostly white with simple designs in mostly red. These colors are usually the best possible complement to traditional icons and woodwork. The geometric simplicity of the designs is important so as not to visually compete with the icon. But beyond this, the patterns in rushnyki vary greatly over time and place. So women today should feel free to develop their own patterns that they find pleasing and meaningful. Churches should encourage this craft as a valued expression of the love of the Saints. If we are really to show the reverence to icons that we claim, we should see to it that our icons are well-painted, displayed properly in shrines, lit with fine lampadas, and honored with beautiful towels.

Consider a secular visitor to an Orthodox church. He may not react well to the treasures displayed in a church. He may ask what is their purpose; why was the money not given to the poor? If he sees an expensive icon in a carved frame, he may dismiss it as the ostentatious gift of a wealthy patron. Perhaps this patron sends his money to church so he need not go himself. But give that icon a clean embroidered towel and a vase of flowers, and all will see that the icon is an expression of living piety, a comfort for the poor. Flowers and linens are, by their nature, temporary and sacrificial. Their presence among the permanent furnishings of a church is like the breath of life in a cold body. In post-Communist countries, many churches are abandoned and semi-ruinous. But even in these empty shells, it is common to find a small icon with a towel and vase of flowers. A village woman still remembers that this is a holy place, and in her piety she maintains this tiny shrine. But what an astonishing effect it has! A great ruin, cold and damp, remains a church and not a tomb because of the devotion of that villager.

[…] https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/an-icon-of-the-kingdom-of-god-the-integrated-expression-of-all-th…Monday, Jun 24th 11:00 amclick to expand… […]

This is a truly wonderful piece and something we will often overlook. The images of village churches show such vitality and care in humble places. I am also very interested in the idea that these patterns are probably pre-Christian. The notion that pre-Christian worlds are preserved in ornament is something I have been pondering for a long time. We see it in the strong endurance of pagan motifs in Roman clavii, but also in the ornamental parts of the great Western cathedrals, or Scandinavian church doors. I believe very much there is spiritual significance in leaving room for the old world on the edge of things, on borders and in margins — a discarded world finding refuge within the knots and fantastical beasts that hide on the limits.

That’s a very interesting point. I hadn’t considered that there is something spiritually important about the presence of these whispers from ancient times. There has been some serious research into the motifs of Romanian embroidered towels. Some of the most traditional designs incorporate simple pictures of female figures, highly abstracted. Scholars have determined with some certainty that these motifs derive from pagan goddesses. I think we can see the use of these images on icon towels as a kind of submission, where the ancient goddesses now bow down to the Christian Saints, much like the pagan Greek deities which appear in the Pentecost and Theophany icons.

That is quite fascinating. Your notion of the goddess bowing down as the water gods in the Theophany icon is very much what I am thinking about. I have been working on a text regarding ornament for while, its relation to periphery in general, hair, nails, rings, but also glory, veil and sacred and how these relate to the garments of skin. The idea of a dead border lingering on the edge of things has much to do with this, and pagan gods hiding in ornament is part of this. Hopefully I will have it ready soon.

google…

G http://images.google.com.hk/…

Dear Andrew: What a joy to rediscover your wonderful contributions to our Orthodox faith and life. This article about linens thrilled me because I am now 81 years old and this tradition has absorbed over forty years of my life. I am rather desperate to find someone to inherit my archives and continue the study. in your article I felt some of my research reflected and when I saw the first picture, I thought: “That isn’t a Romanian towel, It’s Ukrainian” and then I recognized that I took that photo, in the Lemko Church in Wysowa, Poland. Further down the woman being shown the towel is my wife, Anastasia. All this is just to hint that I am desperate to share my research, hundreds of photos and stories. Last year I illustrated and self published a children’s book entitled: “Grandma’s Ritual Towel”. With this post may I invite contact at, a.currier@juno.com ? Again my thanks for honoring this tradition.

Dear Alexsi, I’m glad you saw my brief article here. Indeed, I owe much debt to you for having taught me much of what I’ve written here, and for having provided me with the photos from your travels. Indeed, I wish it were possible to treat the subject at much greater length, but this is not my field of expertise. Perhaps you would be willing to contribute an article to OAJ one day.