Similar Posts

St. Basil the Great (Hieromonk Seraphim Oftalmopoulou, 1956)

Conserve: To protect from loss or harm; to keep quantity and quality constant through physical or chemical reactions or evolutionary changes.

Restore: To bring back into existence or use; to return to an original condition.

Close in definition, the differences when applied to art treasures can be catastrophic. Consider the botched effort to “restore” Elías García Martínez’s 120-year-old fresco “Ecce Homo” which had deteriorated from humidity in the church of Santuario de Misericordia of Borja in northeastern Spain.

Results like this are tragic when artists attempt to repaint the original.

Conservation

“My job is not to paint over injuries,” says conservator Elena Valentinovna King. “My job is first to make sure the artifact is structurally sound. I then carefully remove layers of grime and deteriorated varnish. Typically, I must compensate for losses or disfigurement using conservation grade materials. Finally, I apply a coat of varnish to unify and saturate the surface.”

Elena holds a master degree in art conservation, specializing in Byzantine icons, from St. Petersburg Academy of Art, St. Petersburg, Russia, as well as a master in painting from the Academy. Her expertise is broad, having stabilized hundreds of important icons, including work on 12th century frescos in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Pskov, Russia, and 14th and 15th century icons in the Pskov Museum’s permanent collection. She and her husband moved to the United States in 1997 where Elena worked as senior conservator in several of the country’s top conservation centers before establishing an independent service.

Over the last 11 months, beginning in September 2016, Elena has intermittently worked on site at Panagia Pantovasilissa Greek Orthodox Church in Lexington, Kentucky to preserve the integrity of a precious collection of icons painted in the mid-20th century on Mount Athos.

Panagia Pantovasilissa Church, Eparchy of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople, was the first so named in the United States, having dedicated their church building in 1953. After more than 60 years in the same location on Tates Creek Road, the parish initiated construction of a new church in Fall 2013 and moved their home in December 2015 to the intersection of Tates Creek Road and Rebecca Drive. An important part of the relocation process was the care of the four large icons and 12 smaller icons of the apostles that had been in place on the original iconostasis since the late 1950s.

What’s in the Name? The Patronal Icon of Panagia Pantovasilissa

Greek immigrants began clustering in Central Kentucky after the First World War and several Balkan conflicts. By 1948 they founded the mission parish of Panagia Pantovasilissa in Lexington. The patronal name of the community was derived from an icon that once resided in the great church of Hagia Sophia constructed in Constantinople (532-537) by order of Emperor Justinian I. Shortly before the city fell to Mehmed II on May 29, 1453, the Panagia icon, reputed to be one of the four that Evangelist Luke painted, was dropped into the Marmara Sea, along with other cherished panel icons from Hagia Sophia, to preclude their desecration by invading Ottoman Turks.

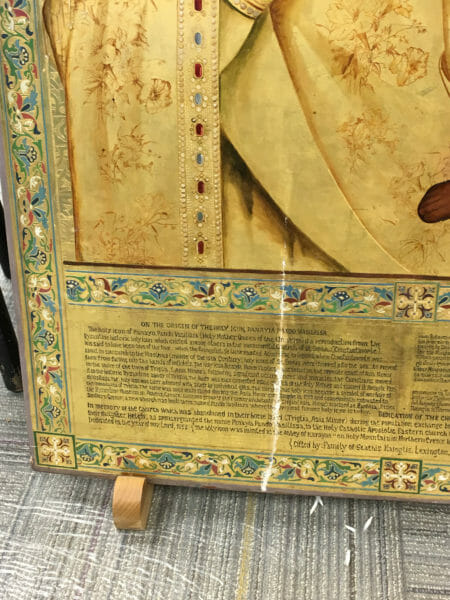

Panagia Pantovasilissa painted by Hieromonk Seraphim Oftalmopoulou of Karayae Monastery on the Holy Mountain, 1956

The Panagia icon was found on the opposite shore of the Marmara near the village of Triglia in Asia Minor. In response to miracles surrounding the arrival and presence of the icon, the citizens of Triglia moved it to a nearby monastery which was later converted to a parish church named Panagia Pantovasilissa in honor of the icon.

The 1918 Armistice of World War I, and the failed campaign of the 1919-1922 Greco-Turkish War to realize the Megali Idea, brought about massive deportations of Greeks from Turkey (Asia Minor). The “Great Idea” of recovering Constantinople (present Istanbul) and her former territories was not to be, but rather an expansion of Turkish control over Asia Minor under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal, Ataurk. Triglia families forced to leave their homes relocated in Raphina, Attica, in southern Greece, taking the icon with them. A new church named Panagia Pantovasilissa was built in Raphina where the original icon is still enshrined today.

Many of the founding families of Lexington’s Panagia Pantovasilissa Church came from Raphina and can trace their ancestry to Triglia where the icon washed ashore after its sea journey from fallen Constantinople in the 15th century. To affirm the parish’s historic relationship with the miraculous icon, Helen Kafoglis commissioned Hieromonk Seraphim Oftalmopoulou of Karayae Monastery on the Holy Mountain (Athos) to paint a copy in honor of her parents, Stathis and Anna Kafoglis, who originated from Triglia. It was delivered to Lexington in 1956. The other icons on the iconostasis, also by Hieromonk Seraphim, arrived in 1959.

Preservation

Helen Collis, an honorary trustee of the Cleveland Museum of Art and former parishioner of Panagia Pantovasilissa, was determined to ensure the preservation of these treasures she had prayed before throughout her youth. Her father had personally excavated the earth with a shovel for the foundation of the first temple on Tates Creek Road. On the recommendation of Dean Yoder, senior conservator for the museum, Mrs. Collis consulted with Elena about taking measures to protect the icons. The parish got behind the effort and raised funds for the project.

Because of Elena’s knowledge of antique materials and her skill in performing structural and cosmetic repairs, the museum had previously commissioned her to stabilize an extremely valuable acquisition before further conservation procedures could go forth. It was a 15th century Eleousa Theotokos icon attributed to Angelos Akotantos, known for marrying Byzantine and Western artistic elements. Angelos was one of the primary artists of the Cretan School, along with Andreas Ritzsos, that coalesced in Heraklion a few decades before the final siege of Constantinople. A century later El Greco (1541-1614) received his early training at this new center of post-Byzantine painting in Heraklion.

Icon of the Mother of God and Infant Christ (Virgin Eleousa), c. 1425-1450. Attributed to Angelos Akotantos (Greek, c. 1450). Tempera and gold on wood panel; unframed: 96 x 70 cm (37 3/4 x 27 1/2 in). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Leonard C. Hanna, Jr. Fund 2010.154

The icons of Panagia Pantovasilissa, while solidly within the Byzantine legacy, reflect this evolution of the Cretan school toward a partial fusion with aspects of Renaissance aesthetics. In contrast with the Panagia itself, which is a copy of a much older prototype, the three other large icons that inhabited the first iconostasis and the icons of the 12 apostles are more painterly. Their portrait-esque modeling using a range of color to determine brilliance and contrast (chiaroscuro) creates a sense of depth. This affinity for one-point perspective is one of the primary characteristics of Renaissance painting.

Detail of face, Pantokrator (Christ Enthroned)

The artist

Hiermonk Seraphim was a mid-twentietn century iconographer and talented painter in the Cretan tradition stylistically influenced by the works of Angelos Akotanto. His icons, like those of Angelos, maintain a passion-less intensity that encourages prayer to the prototype more than admiration for the skill of the artist who created the images.

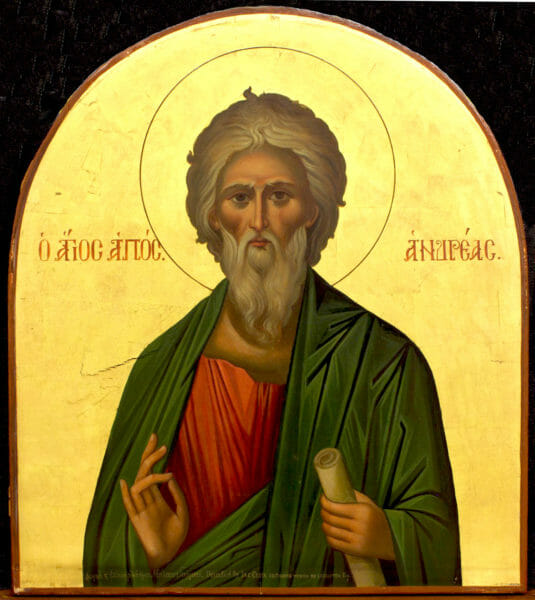

St. Andrew the First Called

The second iconostasis constructed in marble by *Fr. Cosmin Sicoe for the new temple will support four large icons. Besides the Panagia, they are: the Pantokrator (Christ Enthroned), St. John the Forerunner, and St. Basil the Great.

Christ the Pantokrator

St. John the Forerunner and Baptizer

St. Basil the Great

The kisses of ancestors

The work of a conservator is archeological, revealing the material culture of past activity. It is also curative without risking “loss or harm.”

“It is inevitable with time, local atmospherics, smoke from lampades, and the loving gestures of lips and hands, that damages are suffered,” says Elena. Examples of unintended harm are the lip-greased kisses on the icons, some probably dating back to when the icons first arrived from Greece. “There are many kisses on all the icons, the heads and feet. I can do nothing to remove them because lipstick bonds with the paint on a chemical level. If I completely remove the kisses, the paint will come with them down to the gesso. These icons will always be signed with love, the kisses of ancestors.”

Stacks of kisses

Kisses on the foot of Infant Jesus

What Elena can and does do is to patiently clean the icons in stages. Over time, environmental stresses, including oxidation and aging as well as handling, cause weaknesses that lead to cracking, delamination and flaking. Note the fine separation lines on the face of St. Basil (header icon of this article) that expose the white gesso foundation. Inexpert treatment of stress-paths can actually hasten degradation.

The professionally trained conservator begins with analysis of the materials that were used to build the image. The monastic artist of the Holy Mountain who painted the icons of Panagia Pantovasilissa worked in the ancient technique and medium of egg-tempera, which was refined in the imperial schools of Constantinople and Thessaloniki and spread throughout the empire to the Balkans and Russia.

Repairing cracks

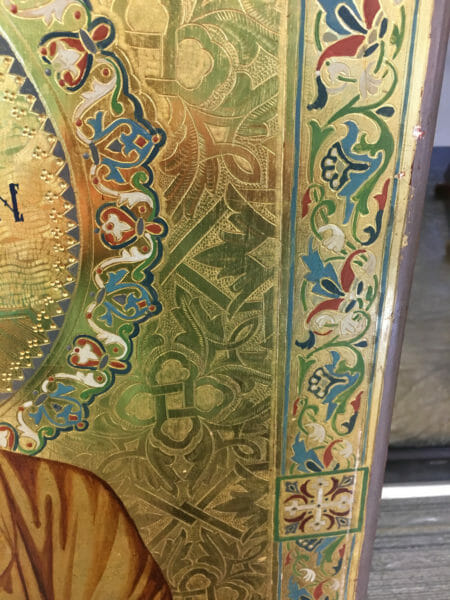

Hiermonk Seraphim of Karayae Abbey, who made a copy of the original Panagia icon from Hagia Sophia, added a detailed inscription in beautiful calligraphy. It describes the history of how the icon came via Triglia to Raphina in southern Greece. A split in the panel cuts through the left quadrant of the script. Splits like this are caused when splines remain taunt but the panel bows.

“These panels were made from pine available on Mount Athos. It’s a very knotty wood that can, in time, declare itself through the gesso to the painted surface. All wood has a very active afterlife; it will always respond to its environment.”

Repairs to this kind of natural wound are surgical though not invasive.

Damaged gold

Hiermonk Seraphim used generous amounts of gold-leaf on all the icons. The fabulous “punch” work on the Panagia is a testament to his skill in this technique of ornamentation.

The conservator uses specialized materials for each type of compromising event. Bruised areas of gold, for example, are treated with mica powders diluted with shellac rather than re-gilding, as some amateurs venture, resulting in signature patches.

The conservator uses specialized materials for each type of compromising event. Bruised areas of gold, for example, are treated with mica powders diluted with shellac rather than re-gilding, as some amateurs venture, resulting in signature patches.

The conservator’s tribute

The icons of Panagia Pantovasilissa Church are “museum quality,” Elena says. But her understanding of their value goes beyond that of art investor and museum collectors. Responding to suggestions that the icons be replaced with newer images for the new location, Elena submitted these remarks in her proposal:

“If these icons are replaced, we lose this connection and part of the rich history and traditions in this community. How many generations offered prayer upon these icons in a moment of despair or through tears of joy? The icons are imbued with the energy of the congregation throughout its history. If these icons are removed and replaced, this connection with the past is lost, leaving the future members disconnected. In Russia, we use the expression namolennaya icona, which means much prayed upon; we consider such icons priceless.”

Inscriptions on the icons of sponsor-grantors

Panagia Icon: Stathis and Anna Kafoglis with their daughter Helen

Pantokrator: Christos Yalanos

John the Forerunner and Baptizer: Nikolaou Anakou Family

Basil the Great: Basiliou Kolliou (uncle of Dr. John Collis anglicized)

Twelve Apostles Icons: Greek Orthodox Youth of Lexington of Kentucky

*Fr. Cosmin Sicoe

Priest of Panagia Pantovasilissa Church from June 2015 to June 2017, who oversaw the completion of the interior narthex, nave and altar areas.

Takeaways for all churches to responsibly address:

1. Soot from lampades, votive candles and incense when left to build up for decades has a corrosive effect on icons. The first layers of soot bond with the varnish, and after successive layers, the icons darken. Minimize direct contact as much as possible and employ a conservator to revitalize the surfaces.

2. Lipstick worn when venerating icons is a kind of accidental vandalism. With the exception of fire and axe, there is hardly a worse threat to an icon. Lipstick forms a double-bond that seals existing grime to the surface and attracts additional debris to be glued to the icon. Educate parishioners to remove lip-grease coloration before kissing an icon.

Elena Valentinovna King also treated the Patron Icon of St. Andrew Orthodox Church, Lexington, Ky, painted by the late Ksenia Mikhailovna Pokrovsky

Dr. John and Mrs. Helen Collis

Thank you for this interesting perspective. On the subject of damage from kissing and lipstick, I often wonder how old the practice of kissing icons really is. I have heard that there are few references to the practice from centuries past.

My own observation has been that an unprotected icon on an analogion in church can easily wear right through to the gesso in 10 years of being kissed. Damage of this kind can be seen in most any Orthodox church nowadays. However, looking at antique icons in museums, we do not observe this particular kind of damage. If these antique icons were used (kissed) for centuries, why would there not be bare spots worn through on the hands? I’ve just never seen it. So I can only conclude that, historically, icons were not kissed in the way they are today. And I don’t think this can be ascribed to lipstick being a modern invention, because it most certainly is not. It has a history older than icons.

I might speculate that the practice of kissing icons actually co-evolved with the practice of protecting them behind glass – a practice begun in the mid-19th century when large sheets of clear plate glass became available.

I’d be very interested if anyone can direct me to research on this topic.

Interesting theory on the history of kissing icons, Andrew. Lacking literature on prior practice or prohibition, probably only data provided by conservators could verify the evidence of, and that merely to the invention of women’s lip-grease. The gesture is a natural one, as natural as kissing ones relatives, and may have a very long tradition.

Thanks for the study, Mary. Can you provide us all with a link or means of contacting Elena Valentinovna King?

Baker, here is contact information for Elena Valentinovna King.

Email: elena.v.king@gmail.com

Phone: 773-592-5739

AG great observations perhaps one can also say that ikons have become fetishes in the modern world and that is why they are kissed , paper reproductions are rubbed on originals, they are talked to etc..

As a monk once said to me in a Russian Church in observing the behavior described above, ” if these people were from the islands ( meaning the Caribbean ; people of color) people would be accusing them of voo-doo.

I would make two comments. First, it appears in the close-up of the icon of St Basil at the top of the article that there are points of light on the eyes such as we see in portrait painting. It is my understanding that this is incorrect because such highlights on the eyes indicate the reflection of natural light whereas in icons the aim is to represent the saint glorified by the Uncreated Light. Secondly, kissing icons was and is not done by Old Rite and Edinoverie Russians, and the practice is arguable.

There is no question that icons such as this St. Basil (which are often termed ‘Italian’ or ‘Romantic’ style) are heavily influenced by western naturalistic painting. So it is not unexpected to see a more naturalistic use of light in them. It would be reasonable to argue that such influences have a regrettable affect on iconography, as they work against some of the pictorial qualities of Byzantine painting that we would consider ‘iconic’. But we must be careful about dogmatizing a style of painting, and calling such things “incorrect”. I am quite sure there is no cannon that forbids shadows and reflections in icons, and even some venerable Byzantine images exhibit an occasional shadow. (For instance, the great Deesis mosaic at H. Sophia). I tend to think it is most helpful to simply observe that there are certain pictorial techniques that support the iconicity of an image, and others that undermine it, but that there are always some contextual exceptions to any ‘rule’ one might devise.

Your information about the Old Believer practice is very interesting. I would be interested to learn more about this.

My wife (who is a Muscovite) and I used to visit the Edinvorie community at Mikhailovskaya Sloboda south-east of Moscow. We knew well the priest there who speaks fluent English and he explained some of the Old Rite practices to us which include not kissing icons. Old Believers follow the same practice. I do not know when the practice of kissing icons was introduced but like all post-Nikonian practices, it is rejected by the Old Rite and Old Believers faithful.

As to highlights on the eyes of saints portrayed in icons, one would have to say that we are talking here not about style but about meaning. There are many ‘icons’ perpetrated today that are obviously uncanonical in ways which are not addressed by the canons but which nevertheless flout established tradition.