Similar Posts

____________________________________________________________

Editorial note: We have convinced Aidan Hart to post a chapter from his new book. “Techniques of Icon and Wall Painting” which is being hailed as the most comprehensive book to date on practicing the art of Iconography. At 450 pages, with 460 paintings, 150 drawings and covering everything from theology and design to gilding and varnishing, it is a prized possession for anyone interested in the traditional arts. The chapter being serialized over the next weeks is called “Designing Icons”. You will see why Archimandrate Vasileos of Iviron called this book the “Confessio of a man who epitomizes the liturgical beauty of the Orthodox Church”. More details about the book on Aidan’s website.

Editorial note: We have convinced Aidan Hart to post a chapter from his new book. “Techniques of Icon and Wall Painting” which is being hailed as the most comprehensive book to date on practicing the art of Iconography. At 450 pages, with 460 paintings, 150 drawings and covering everything from theology and design to gilding and varnishing, it is a prized possession for anyone interested in the traditional arts. The chapter being serialized over the next weeks is called “Designing Icons”. You will see why Archimandrate Vasileos of Iviron called this book the “Confessio of a man who epitomizes the liturgical beauty of the Orthodox Church”. More details about the book on Aidan’s website.

____________________________________________________________

This is part 7 of a series. Part 1, Part 2 , Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6

Architectural settings

In iconography, a saint or event may be depicted against a gold or a plain background. They can also be placed in an architectural setting in order to express something of their life, or in the case of a feast, the theology of the event.

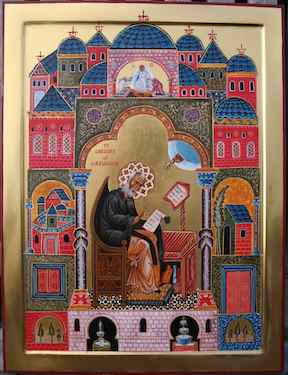

The illustrated contemporary icon shows St Gregory Nazianzus set among buildings adapted from a twelfth century illumination. The commissioning client intended to use the icon to illustrate his lectures on the saint’s theology and life. He wanted it to reflect St. Gregory’s tension between his natural inclination for contemplation in the solitude of his country retreat, and the Church’s need of him in the city to defend the faith against heresy. We agreed that the icon had to be boldly coloured so it could be easily read at a distance as an educational aid, and that it should contain the maximum teaching material without becoming cluttered.

We decided to base the icon on a well known illumination of the saint found in St Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai. As in the manuscript, this icon shows the saint seated within an abstracted church structure. He is writing, which indicates his teaching ministry. And although a bishop, in this icon he is shown not in his liturgical vestments but in his monastic habit in order to highlight his contemplative inclination. As with the manuscript we used rich but natural pigments – cinnabar, azurite, malachite and transparent earths.

We however changed surrounding elements of the original illumination in order to express St. Gregory’s tension between city and countryside. We incorporated to his left a city as seen through a window, while on the other side we included a monastic cell set in a garden.

The Resurrection icon was painted in a lunette above the saint, in honour of the house-church in Constantinople dedicated to that feast where St. Gregory preached his most formative sermons on the Trinity.

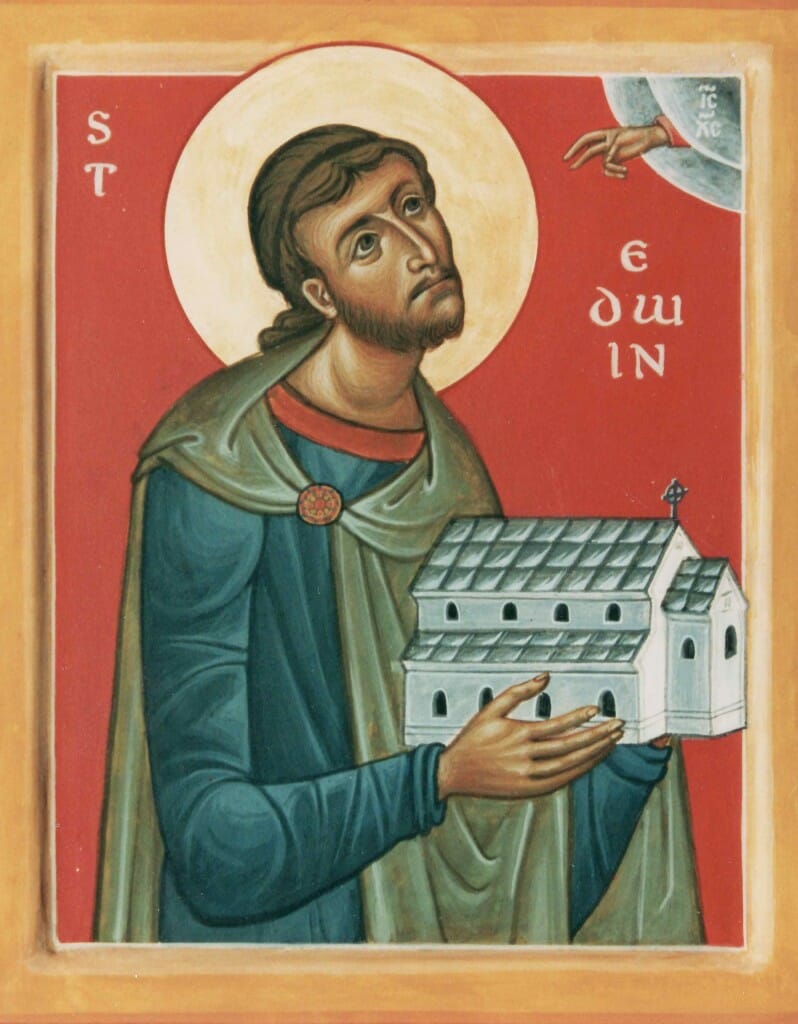

Architecture can also be used to identify a saint’s cultural context. If they founded a church in Russia, for example, they can be shown holding a Russian styled church, or an Anglo-Saxon church if in England

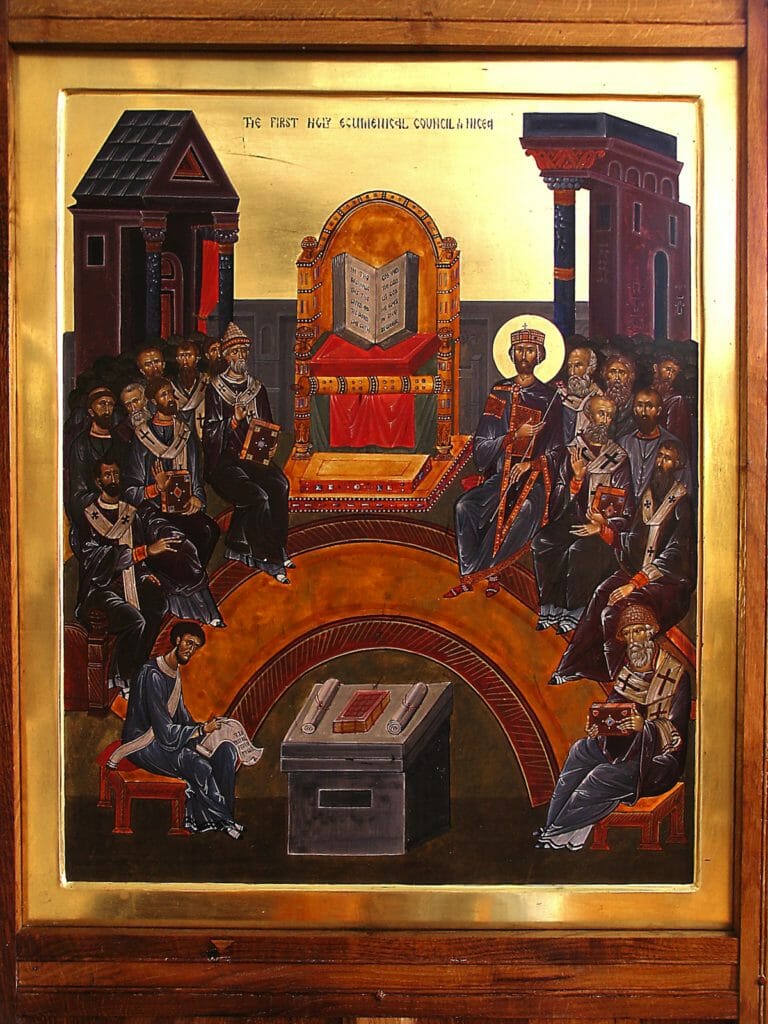

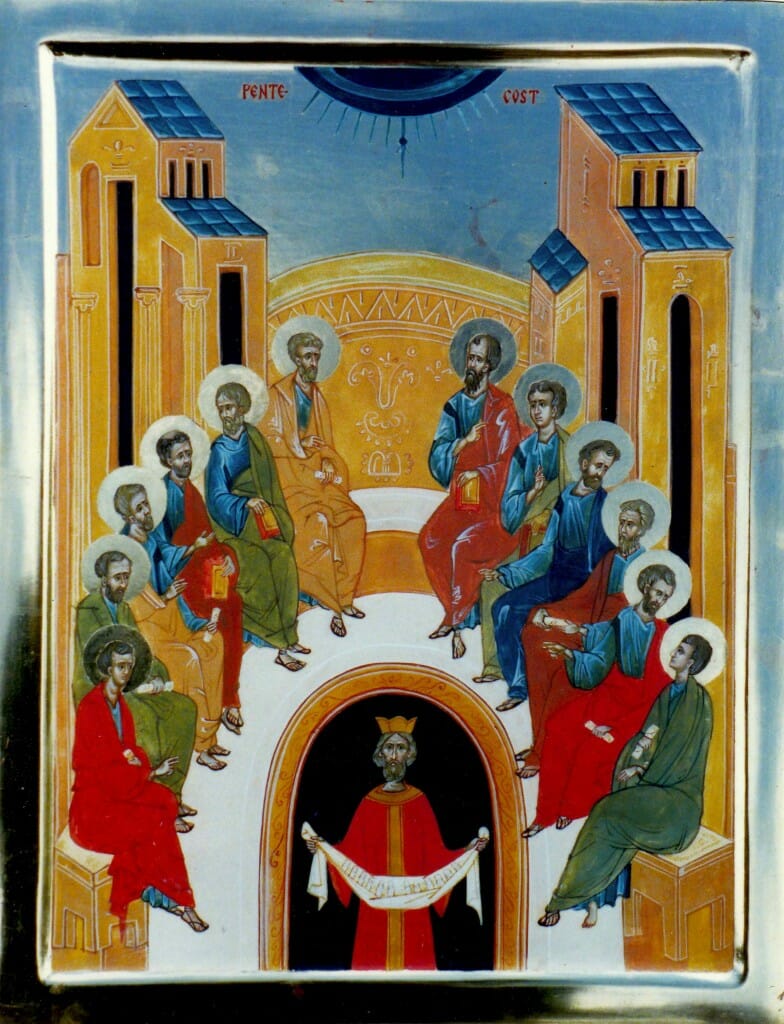

Festal icons particularly lend themselves to the symbolic use of architecture. Below we discuss the symbolism of the horseshoe shaped bench in the Pentecost icon. Here we consider how an icon of the First Ecumenical Council makes rich use of architecture

. The architectural and furnishing features was based on a very early illuminated manuscript of the council:

- The Episcopal throne in the centre affirms that Christ is the High Priest, of whom each of the gathered bishops are a sacramental image. It should ultimately be He who presides and guides the council, and not they as autonomous authorities. The Scriptures are seated on the throne, showing that the council of bishops was behoven to follow the received teachings of Christ. They devised new phrases, but to express old truths.

- The altar below has on it the Scriptures, but this time in their liturgical context. The two scrolls either side are the liturgical texts of the Church, those of the Holy Liturgy in particular. The presence of the altar – or the Holy Table as it is more often called in the Orthodox Church – places this council of Bishops squarely within the context of her liturgical life. The council took place not in a palace, but in a church – Saint Irene. What the bishops sought for was an expression of the truth as experienced and affirmed through the Church’s worship and prayer. Right dogma is right worship or glory (doxa in the Greek), hence the term ortho-doxy.

- In front of the Holy Table is a recess, which housed the relic of a martyr. In the early centuries of the Church many churches and their altars were built over the burial place of a martyr. Later, relics were kept in a sort of liturgical safe in the front of the altar.

Altar in Ravenna

-

Later practice has been to imbed them in the top of the Holy Table at its consecration, and to sew them in the cloth antimensian used at every liturgy. The presence of these relics reminds us that the Body of Christ “fills up the sufferings of Christ” as Saint Paul puts it. If the master suffers at the hands of evil men so will His servants. And there were present at this first council many confessors, people who had upon their bodies the scars of torture and persecution.

- The curved bench upon which the bishops sit is of the type found in the apse of many churches, which emphasizes again the link between doctrine and worship. But this shape also echoes the bench shape invariably used in the Pentecost icon

The bishops arrive at the truth not merely by intellectual prowess, but by living experience of the Holy Spirit; true doctrine is simply an accurate description of what one knows of God through the Spirit. This shape suggests various images used in Orthodox hymns of Pentecost, and these are all equally applicable to this feast: a trumpet, a net, a surgery for healing, a philosopher’s academy, a chalice.

- If an event has taken place inside, there is usually a red cloth draped between two structures in the background. This is not done in our icon, but it is nevertheless made obvious by the presence of the buildings.

- The lines of perspective used for the buildings in our icon clearly follow rules other than those of the vanishing point system used almost exclusively in the West since the Renaissance. But we will leave a discussion of iconographic perspective for more detailed discussion below.

Natural settings

Sometimes people want to include elements from nature that are associated not only with the saint’s life but also with the place for which the icon is intended. These can be included as long as they do not clutter the image and detract from the icon’s primary purpose of helping us establish a relationship with the saint. Everything must be placed and scaled so as to draw us to the saint.

The illustrated icon of Francis of Assisi was one such commission. It was destined for a church on a hilltop village in Spain, restored by the donor’s father. This was included in the background to the saint’s right, and balanced to his left by birds associated with that place and the donor. A cinnabar red background was chosen not only to signify the life-giving presence of God, but also to suggest the heat of Spain and Francis’s Italy.

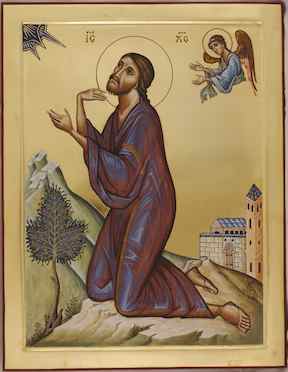

Mountains often express the spiritual dynamics of an event. We see this in the Garden of Gethsemane illustrated above. Christ is “sorrowful, even to death” and prays with profound anguish. This is reflected in the upward sweep of the jagged mountain.

In the above illustrated icon of the Harrowing of Hades, the rocks appear like the jaws of Hades opening to free the captives imprisoned within.

In the above icon of the Transfiguration the mountain is subdivided into three distinct rocks to affirm that union with Christ retains the distinction of persons. Note also the two caves, filled with light (gold leaf). Both Moses and Elijah, either side of Christ, experienced partial epiphanies in places related to caves. Moses was hid in the cleft of a rock as God passed by, and he saw only “the back parts of God”. Elijah went to the mouth of the cave where he was hiding and heard God as a “still small voice”. But here on Mount Tabor, they behold God face to face in the person of Christ. The dark cave of partial revelation is filled with the dazzling splendour of the transfiguration.

[…] Icons (pt.7): Architectural and Natural Settings in Icons https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/designing-icons-pt-7-architectural-and-natural-settings-in-icons/Friday, Feb 8th 2:34 pmclick to expand…A “New” Orthodox Blog […]

ORTHODOX WORLD…

http://www.linkurigratuite.info…

[…] This is part 7 of a series. Part 1, Part 2 , Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, […]