Similar Posts

____________________________________________________________

Editorial note: We have convinced Aidan Hart to post a chapter from his new book. “Techniques of Icon and Wall Painting” which is being hailed as the most comprehensive book to date on practicing the art of Iconography. At 450 pages, with 460 paintings, 150 drawings and covering everything from theology and design to gilding and varnishing, it is a prized possession for anyone interested in the traditional arts. The chapter being serialized over the next weeks is called “Designing Icons”. You will see why Archimandrate Vasileos of Iviron called this book the “Confessio of a man who epitomizes the liturgical beauty of the Orthodox Church”. More details about the book on Aidan’s website.

Editorial note: We have convinced Aidan Hart to post a chapter from his new book. “Techniques of Icon and Wall Painting” which is being hailed as the most comprehensive book to date on practicing the art of Iconography. At 450 pages, with 460 paintings, 150 drawings and covering everything from theology and design to gilding and varnishing, it is a prized possession for anyone interested in the traditional arts. The chapter being serialized over the next weeks is called “Designing Icons”. You will see why Archimandrate Vasileos of Iviron called this book the “Confessio of a man who epitomizes the liturgical beauty of the Orthodox Church”. More details about the book on Aidan’s website.

____________________________________________________________

In this section, Aidan discusses the different perspective systems used in icons.

This is part 9 of a series. Part 1, Part 2 , Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8

Inverse perspective.

With inverse perspective the lines of a building do not converge on a point on the horizon, inside the painting, but instead they converge on us, the viewers. This serves to include us in the action depicted. The Orthodox hymns make it plain that a sacred event in the past is still acting on us today: “Today Christ is born”, they say, “Today Christ is risen. Let us join with the angels in praising His third day resurrection!”

An example of inverse perspective. The Hospitality of Abraham / “Old Testament Trinity” by Fr. Silouan

Inverse perspective also gives us the sense that the persons depicted are looking out at us. It is as though the image is drawn not from our own point of view but theirs, and ultimately, God’s. We have already discussed the meaning of repentance as being a change of seeing. We could also explain it as a change of perspective, where we realize that we are not the centre of the universe, but God.

Inverse perspective also draws our attention to the real space between the image and ourselves. The emphasis is on the grace coming to us through real space, rather than us being drawn into an imaginary world or reconstructed scene within the picture. Iconography is above all a liturgical art, designed to be part of a larger sacred dance that involves the church building, the space within the building, the hymns sung within it, and the liturgical movements during services. As Gervase Mathews puts it:

In the Renaissance system of perspective the picture is conceived as a window opening on to a space beyond…The Byzantine mosaic or picture opens onto the space before it. The ‘picture space’ of Byzantine art was primarily that of the church or palace room in which it was placed, since art was considered a function of architecture.[1]

Flatness

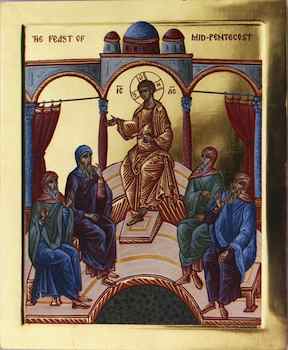

Icons do not attempt to create a great sense of depth. They do use enough highlighting and perspective to affirm that the material world is real and good and part of the spiritual life. Nevertheless, things are kept somewhat more on a plane than in naturalistic painting. In a group icon, like that of Mid-Pentecost for example, people in the rear will be shown the same size, or sometimes even larger, than those closer. Every person is thus kept intimate with the viewer. The mystery of the person overcomes the limits of physical space and distance.

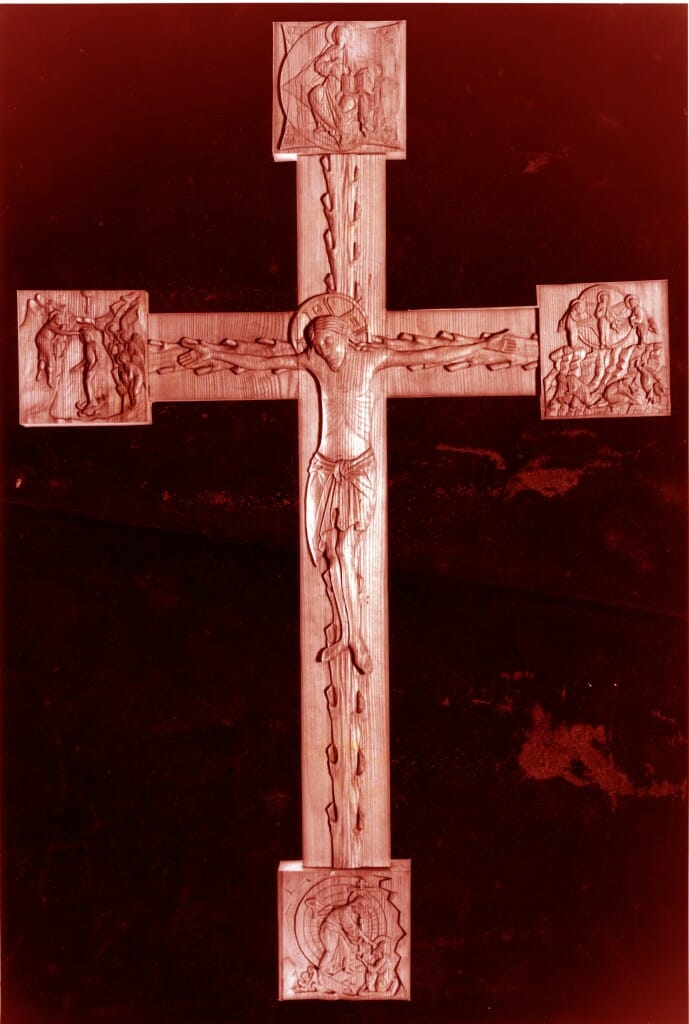

Why else do icons retain this flatness? It helps us to pass through the icon to the persons and the events depicted. The aim of the icon is not to replace the subjects depicted, but to bring us into living relationship with them. This explains why statues are not as a rule used in the icon tradition. Their three dimensionality makes them too self contained. Where sculpture is utilized it is kept to base relief.

Flatness can also be seen as a intentional weakness, a deliberate imperfection that constantly reminds us that this image is not the reality but a door to its prototype.

There is also an honesty in this flatness. There no attempt to make the picture plane what it can never be, a three dimensional object, let alone the real thing itself. Incidentally it is this honesty to the picture plane that inspired the American art movement called colour field painting of the 1940’s and 1950’s.

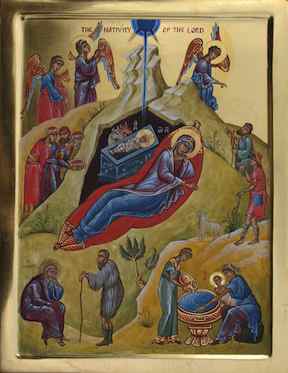

Planarity also gives much greater freedom to arrange things according to their spiritual importance rather than being limited to their position in three-dimensional space. The figures within the icon of Christ’s birth, for example, are often arranged in three bands to represent the heavenly, earthly and unitary realms, and also in a circle centred on the Christ child

This symbolic arrangement would not be possible if the event were depicted naturalistically, with figures receding toward the distance.

Multi-view perspective

Sometimes a building is shown as though seen simultaneously from left and right, below and above. This helps us to see things as God sees them, and as they are in themselves and not merely as they appear from our single view-point, limited as this is to one place at a time.

The same multi-view perspective is sometimes applied to time, where the same person is depicted more than once in the same image, such as with Christ in the Nativity icon. The icon tradition can also place an important person in an event at which they were not historically present, but in which they later came to participate spiritually. Icons show things from the view of divine time (kairos in Greek) and not merely chronological time (kronos). One example is Saint Paul in the Pentecost icon (fig. PentecostIMG copy.tif). He was not even a believer at the time of Pentecost, but later came to be great among the apostles and a pillar of the Church together with Peter, who is shown opposite him.

Isometry

In this approach the sides and edges of an object are depicted parallel, neither converging nor diverging. This affirms how a thing is in itself, rather than how it appears to us. All things have been called into unity in Christ, and this unity preserves and strengthens the integrity of each thing, rather than reducing it to a numerical one. Unity presupposes relationship which in turn presupposes otherness, though not separateness. Isometry affirms this otherness.

Hierarchical perspective

Often a personage who is more important than others will be enlarged. A typical example of this is the Virgin in the Nativity icon (see Nativity icon posted above). Conversely someone might be made particularly small to make a spiritual point. The Christ Child is often depicted thus in Nativity icons, to emphasize God the Word’s humility in becoming man for our sakes.

Vanishing point perspective

Although inverse perspective is more commonly used, we do also find instances where lines converge toward a point in the icon’s distance. This is not pursued in the systematic, mathematical way devised by the Renaissance painter, architect and sculptor Alberti Brunelleschi. In fact when this system is used you are likely to find as many convergence points as there are objects. This in itself transports the viewer out of the static vantage point assumed by mathematical perspective, and presupposes instead a much more dynamic experience – surely something closer to our actual experience of life.

[1] Gervase Mathews, page 30.

[…] https://orthodoxartsjournal.org/designing-icons-pt-8-perspective-systems-in-icons/Tuesday, Apr 16th 7:45 amclick to expand… […]

Excellent article. Thank you for your permission to repost this to my blog which is the Fra Angelico Institute for the Sacred Arts website (fraangelicoinstitute.com).