Similar Posts

What Is It a Sign of?

Among Western Christians, there is a very clear interest in icons. Following Orthodox Christians themselves, certain Catholics and Protestants have rediscovered canonical icons, that is, Christian images that have been shaped and supported by the common ecclesial Tradition of the first millennium, before the schism between the Greek East and the Latin West. The subject of the second half of this study is precisely the evaluation of this new interest in icons.

Point of view of an Orthodox

There is a widespread idea in scientific and academic circles that claims that it is possible to deal with a subject “objectively,” that is, without any preconceived ideas on the basis of which a particular question is studied. I strongly doubt that it is possible for human beings to eliminate their assumptions from such investigations. It is therefore preferable to set out one’s orientation right from the beginning. Having done that, then an application of a rigorously critical mind is a must in all research. So here is my orientation: I am writing on the subject of icons from the point of view of an Orthodox Christian whose interest and specialization is iconology — the study of the history and theology of the icon. I am not an iconographer. Therefore, not having an objective point of view, I hope nonetheless to exercise a critical mind in dealing with this subject.

The icon: a specifically Christian image

It is often said that the Christian Church has not produced or adopted any particular, specific, artistic style and that it is open to all tastes, to all manners of representing the events and people of salvation history. Naturally, such representations are subject to certain wide criteria of appropriateness, decency, artistic quality, etc. Has not Vatican II said it very well?

Very rightly the fine arts are considered to rank among the noblest activities of man’s genius, and this applies especially to religious art and to its highest achievement, which is sacred art. […]

The Church has not adopted any particular style of art as her very own; she has admitted styles from every period according to the natural talents and circumstances of peoples, and the needs of the various rites. Thus, in the course of the centuries, she has brought into being a treasury of art which must be very carefully preserved. The art of our own days, coming from every race and region, shall also be given free scope in the Church, provided that it adorns the sacred buildings and holy rites with due reverence and honor; thereby it is enabled to contribute its own voice to that wonderful chorus of praise in honor of the Catholic faith sung by great men in times gone by[1].

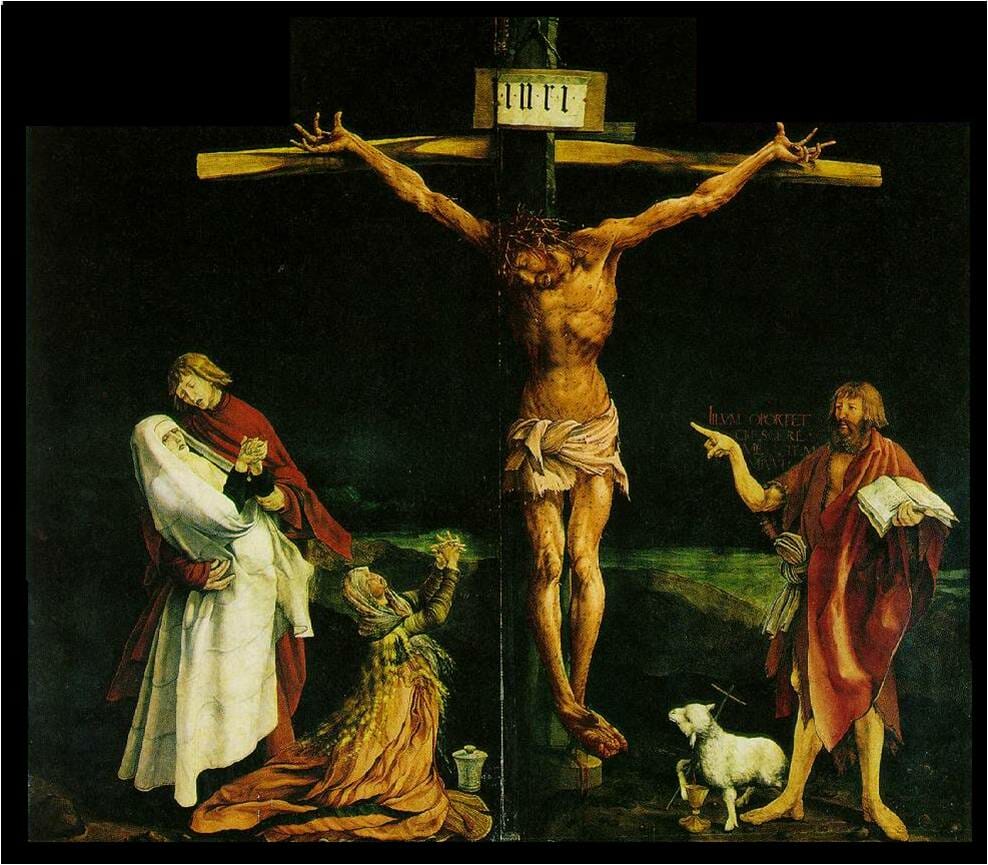

We therefore speak of the following styles: Paleochristian, Oriental, Imperial, Byzantine, Romanesque, Novgorodian, Gothic, Renaissance, Cretan, Baroque, Late Bulgarian, Modern, etc. Consequently, new styles of Christian art, new Christian images, will emerge in the future, and they will conform to the spirit and the taste of their period, while still remaining worthy of being called Christian. This point of view seems so obvious and reasonable that few people would even imagine anything else.

I would nonetheless like to set out the opposite point of view. During the first 1000 years of its history, the Church did create images, either of people or of events of salvation history, which express its theological vision. As the Church through bitter disputes formulated the verbal and conceptual language of its faith, it also developed an artistic vocabulary and language that expressed the same faith, but in colors, lines, and forms. This historical development, this creative process, resulted in what is called canonical iconography, that is, a common artistic and theological treasure, which before the schism between the East and the West, was shared by the whole of the Christian world. After the separation, this treasure was perpetuated, then marginalized, and rediscovered by the Orthodox Church. During the second 1000 years of Christian history, after the schism, the Latin West followed a different path which produced other artistic languages. In the Catholic and Protestant churches, we find today side by side images that “speak” the artistic languages that have succeeded each other up to today. In Orthodox churches of our time, we can also see side by side images of the medieval Byzantine period, of the period of decadence — nearly the loss of canonical iconography — and of the renaissance of traditional icons.

It is not that the iconic tradition of the Orthodox Church has not known various “styles.” We can certainly identify different manners of making images, and we can identify their specific period and country. The description of these manners is the work of art historians. A canonical icon from the Paleologan period is not exactly the same thing as the same icon painted in Novgorod, Macedonia, Crete, or Serbia at various periods. But the Orthodox Church claims that there is a universal, canonical iconography that is expressed by each of these historical and geographical “styles.”[2]

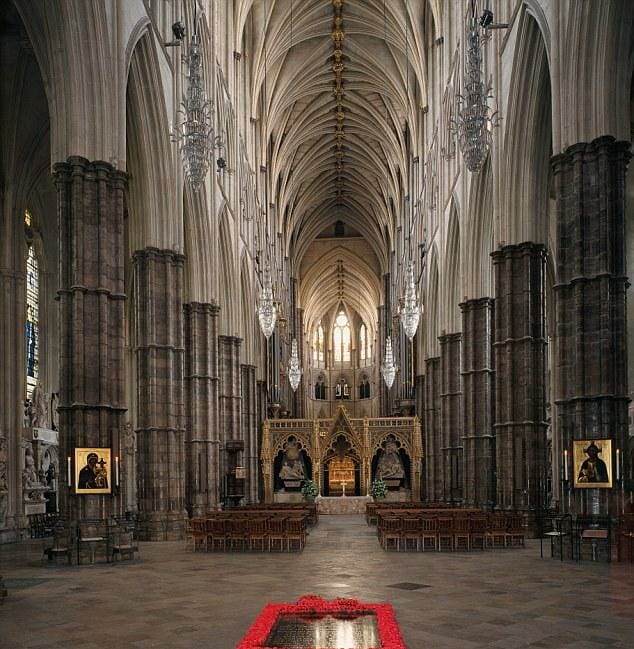

A juxtaposition of artistic “style” at Chinchester Cathedral.

Canonical iconography: a theological art

As we have written elsewhere[3], canonical icons form a theological art in the sense that they represent, manifest, and make visible the same theological vision that the Scriptures, the writings of the Fathers, the decisions of the councils etc. proclaim. The definition of the orthodox faith, in words and concepts, through history, the faith that was shared by the two great halfs of Christianity before the schism, the Greek and the Latin , went hand in hand with a parallel development in the realm of art, i.e. canonical iconography. As a written or verbal expressions of the faith can err, be condemned, and be called heretical, in the same way visual expressions, whatever their material support, can also betray the faith and be designated heretical. From this point of view, it is not the artist who paints an icon, but it is the Church using the artist’s talent that expresses its faith. Equally from this point of view, authors of dogmatic texts are only the chosen instruments who express in words the Church’s faith. Canonical iconography is therefore an ecclesial art which has been fully integrated into the liturgy itself[4].

The Western attitude

Charlemagne, or rather his court theologians, are the first as far as I know to express another attitude about Christian images: “Images are the product of the fantasy [imagination] of artists[5].” In other words, Christian images, whether it is the subject of the work, the manner of painting it, or its material support, are matters for the artists, their talent, creativity, and imagination — “fantasy.” The Church’s role is to watch over the production of images in churches and to guarantee, within wide limits, the decency, artistic quality, and beauty of the works. An image created by a Christian artist is in no way different from a work created by other kinds of artists. Again the Libri Carolini:

They [the Fathers of Nicæa II] said in effect that the painter’s art is pious [sacred], as if it did not share the fate of the other arts of this world in being either sometimes pious [sacred] sometimes impious [profane]. For what does the painter’s art have that is in fact more pious [sacred] than the art of carpenters, sculptors, smelters, chiselers, stone carvers, wood carvers, farmers, and other workers? All these arts that we have just mentioned, arts that can only be learned through the guidance of a master, can be exercised by trained people either in piety or in impiety. And these attitudes, piety or impiety, do not concern the arts in themselves, but the men who practice them. These artists are often either prisoners of many turbulent vices or else are clothed with the saving garland of virtues[6]

Paul Evdokimov could even say about the Libri Carolini that they “poisoned the source of Western art[7].” It is this attitude toward Christian images that Western Christians have adopted, and it is at the base of the historical succession of styles, types, models, etc. that Vatican II spoke about.

[1] Sacrosanctum concilium, Chapter VII: “Sacred Art and Sacred Furnishings,” 122-123, http://www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_const_19631204_sacrosanctum-concilium_en.html

[2] I hope one day to finish a study along these lines that will show that Romanesque painting, 900-1200, is the last Western art of an iconic nature.

[3] « Ce qu’est l’art de l’icône ─ Un lexique », L’icône dans la tradition orthodoxe, Montréal, Médiaspaul, 1995, pp. 33 ff.

[4] Ibid., pp. 41 ff.

[5] The Libri Carolini 2, 26, quoted in Leonid Ouspensky, La Théologie de l’icône, Paris, Les Éditions du Cerf, 1980, p. 125.

[6] Ibid. 3, 22, Daniel Menozzi, quoted in Les images : l’Église et les arts visuels, Paris, Les Éditions du Cerf, 1991, p. 108.

[7] L’art sacré, 9-10, Paris, 1953, p. 20.