Similar Posts

Some Other Points

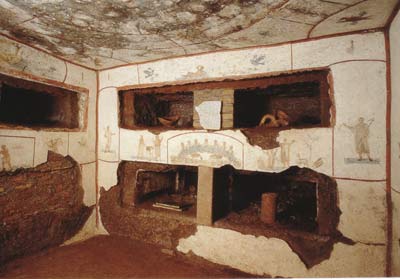

Early Christian art in the Catacombs of Callistus

The Silence of the New Testament

To support their theological arguments, the iconoclasts said that the silence of the New Testament on the question of Christian images supports their rejection of them. It is of course quite true that the New Testament says nothing on the subject, but the iconodules answered that Christ did not command anyone to write the New Testament either. There are many things that Christians say and do which do not have their authorization in the New Testament: produce Christian Scriptures, construct Christian temples, celebrate Easter once a year on a changing date, celebrate Christmas on December 25, align the borders of Church dioceses and provinces with those of the State, recognize that Christian ministers have the right to admit those who have committed serious sins after baptism back in to the communion of the Church, etc. In any case, everything is not written in the New Testament, and the argument from silence is not sufficient. We have here the principle which recognizes the Scriptures as an expression, though not exhaustive, of the oral Tradition of the Church, a principle that recognizes opinions and practices that have their origin in the apostolic preaching, the essential element of which is contained in the New Testament, but the content of the preaching, the kerygma, is wider that the written documents. We have here the rejection of the principle of sola scriptura.

This iconoclastic argument is not directly tied to the theology of Christian images, either iconoclastic or iconodule, but it touches on a related historical question. Nicæa II affirmed that not only an iconodule attitude, that is one that is favorable to Christian images, but also the production of them, goes back to the apostles. This is an intuition based on Church traditions claiming that Christ and the apostles produced images. For Christ, there is the famous cloth image he made of his face and sent to King Abgar; for the apostles, there is St. Luke’s portrait of the Virgin and the Christ-Child. Despite the fact that these traditions cannot be historically corroborated, Orthodox Christians continue to believe that the first Christians, in one way or another, used art, drawings, images to express their faith. Obviously, on the question of the relation between the Scriptures and Tradition, there continue to be many points of views among Christians.

12th-century copper plaque of the Theotokos Hodegtria (Directress), based on the icon painted by St. Luke.

The Ecumenical Councils

The iconoclasts stated that the great Ecumenical Councils — from Nicæa I (325) until Constantinople III (681) — said nothing on the subject of Christian images. This statement is almost true, except for three canons of the Qunisext Council in 681. This council is viewed as the extension of the 5th and 6th councils which issued no canons. Qunisext issued 102 new canons to regulate the life of the Church. Three of them deal specifically with images: canon 72 prohibits crosses on the floor where they can be walked on and dishonored; canon 82 prescribes that the image of Christ’s incarnation, his portrait, should replace symbolic images of him as the Lamb of God; and canon 100 forbids indecent and sensually provocative images in churches. It seems almost impossible that they had never heard about these canons.

Apart from these three canons, however, the iconoclasts were right in claiming that the Ecumenical Councils had said nothing about Christian images. Some iconodules, however admitted that the statement is correct. But by claiming that this silence is rather an argument for Christian images and against the iconoclastic claim — that the idolatrous practice of making and venerating Christian images had slowly and subtly infiltrated the Church, “under the radar” of Church leaders. These iconodules repudiated the claim that the entire tradition of Christian art seeped into the Church without anyone being aware of it as less than credible. Archaeology, artistic monuments, and patristic texts which discuss images make such a claim absurd. These same iconodules affirmed moreover, that since the bishops gathered in Ecumenical Councils knew very well about the existence of images in the churches and did not say anything against them, they could not have believed that Christian images were idols. It is impossible to believe that the bishops of the six great universal councils would have ignored the infiltration of idolatry into the Church if they had seen Christian images as idols. The answer of these iconodules carries great weight for Orthodox and Catholics, but is more problematic for Protestants who have a variety of opinions on the authority of such councils.

The Fathers of the Church

The iconoclasts, like the iconodules, could not ignore the rich treasure of patristic writings, the Fathers of the Church, which goes right back to the apostolic preaching. In the works of the Fathers, both camps naturally looked for texts that seemed to support their position. The iconodules accused the iconoclasts of inventing certain texts, of falsifying others, and of incorrectly interpreting still others. Here we have indirect arguments on the theology of Christian images based on history and texts. It is possible to have various opinions about the authenticity of such patristic texts as well as about the authority of the authors, even if their works are judged authentic. The authority of the Fathers is still evaluated differently among today’s Churches. In fact, it can be seen as an element of the question of the relation between Tradition and the Scriptures. In any event, there is not much unity on this question, and opinions remain sharply divided.

Conclusion

As for the question of Christian images, we have seen that there exists among Christians today a wide consensus and that in the case of nearly all the accusations launched by the iconoclasts against the iconodules, contemporary Christians identify with the answers of Nicæa II rather than with the positions put forward by the iconoclasts. Seen from this point of view, the vast majority of Christians today are orthodox — that is, in agreement with the Scriptures — and can thus proclaim one faith regarding Christian images. We can therefore only rejoice at the fact that the members of the Council of Nicæa II are our Fathers because they affirmed and proclaimed our faith about images