Similar Posts

Editor’s note: This article addresses the Typika Psalms and Beatitudes in the Divine Liturgy, and describes the differences in usage among contemporary North American Orthodox jurisdictions. In particular, the author considers opportunities in which choirs in the Greek and Antiochian Archdioceses might expand their use of these liturgical texts.

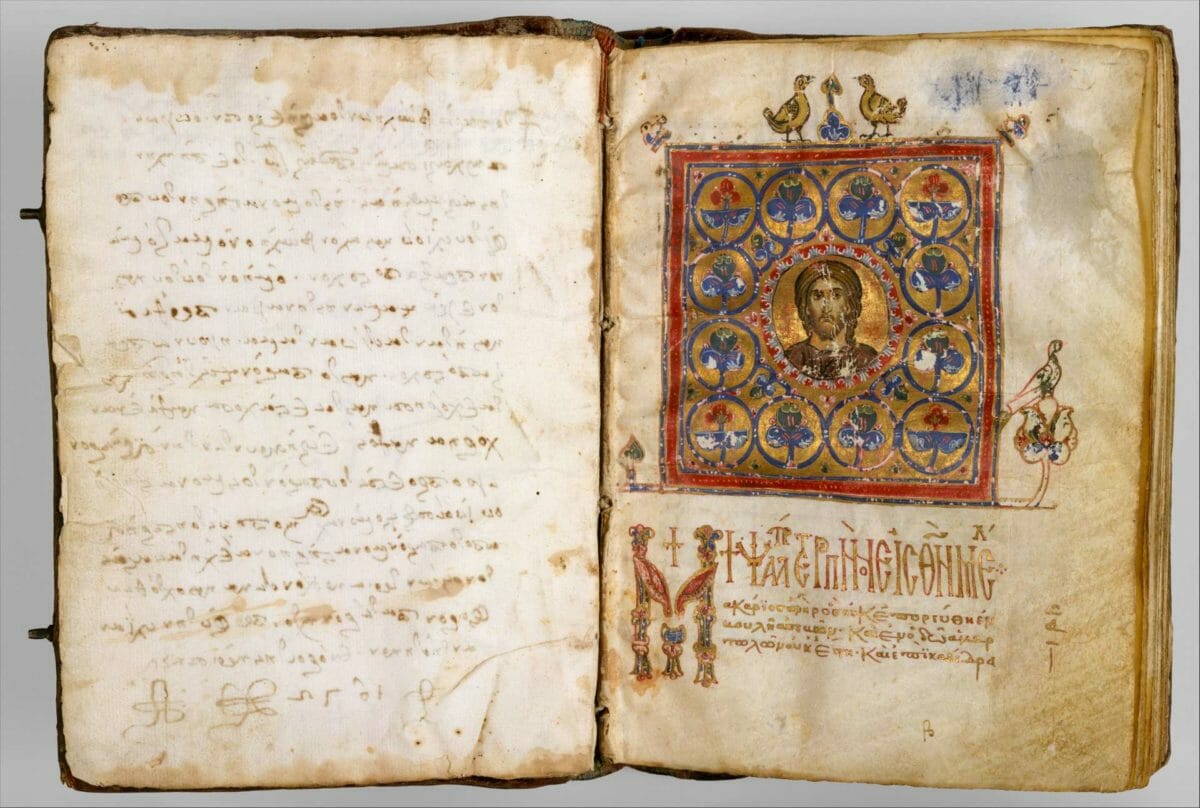

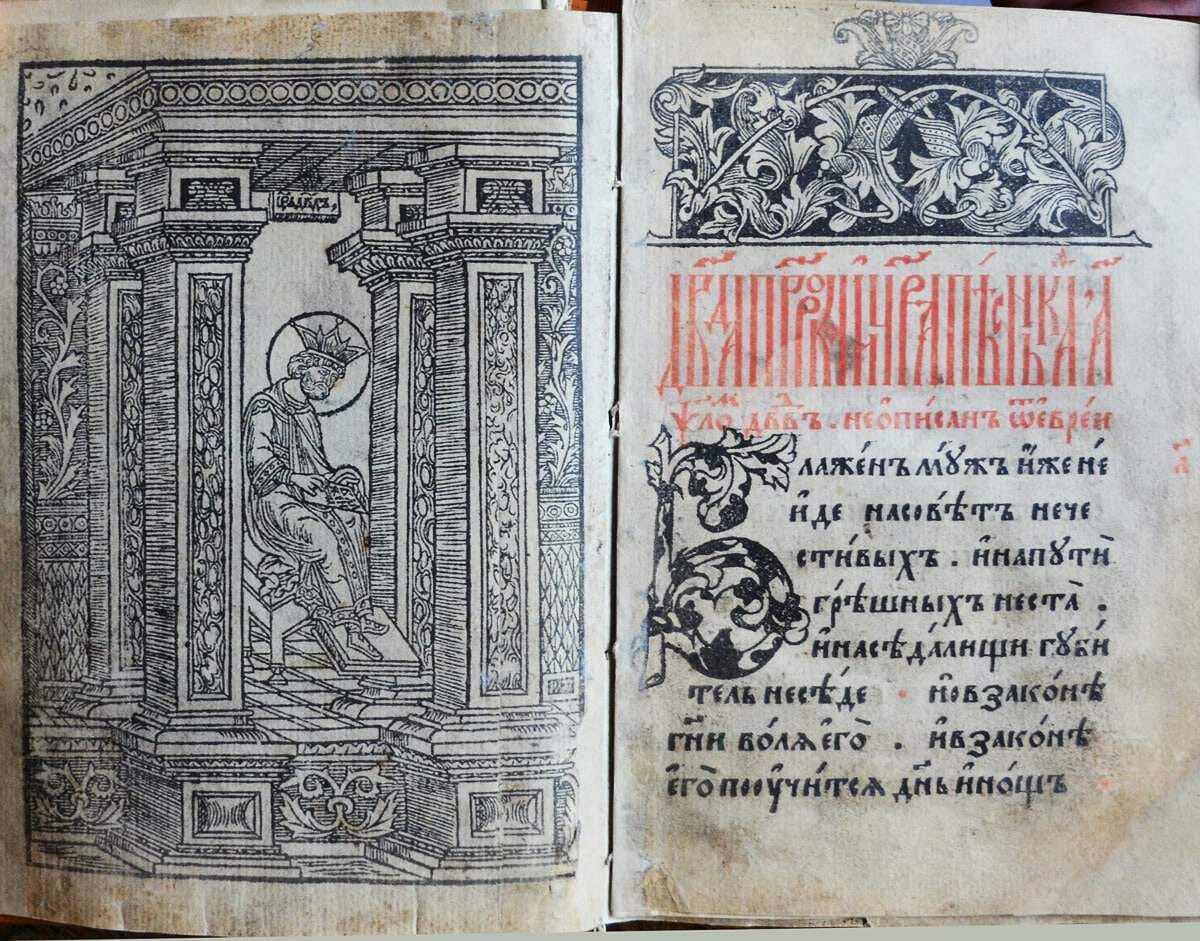

It is frequently observed that the Psalter is the chief source for liturgical and sung texts in Orthodox worship. Translator Donald Sheehan of blessed memory wrote that the psalms are “central to liturgical life and are most often chanted”; Fr. Lazarus Moore of blessed memory called it “[The Church’s] chief book of devotion.” The foreword of one of the more common English-language liturgical psalters notes that “…there is no service of the Church that is not replete with psalms: the Hours, Compline, Vespers, Matins, even the Divine Liturgy itself; all begin and end with psalms… In short, the psalms serve as the framework for all our Church services[.]” Other writers have been more poetic about this sentiment: “The Psalms run like a golden thread through the beautiful garment of Orthodox worship.”

The integration of psalms in Orthodox worship, however, has a complex history. Despite their centrality, Fr. Ephrem Lash of blessed memory once offered a somewhat cheeky observation: “[T]he Orthodox: once they see a psalm coming into view, they cut it out… They don’t do psalms. They wait for the ‘important bits’ by some monk. The fact that the psalms are the word of God is neither here nor there: it’s a waste of time.” Alexander Lingas makes a similar observation with a straighter face: “[M]any [abbreviations of services] reinforce the longstanding Byzantine tendency to omit biblical psalmody rather than the hymnody attached to it[.]” Fr. Ephrem’s bon mot must of course be taken in the spirit offered, but it is unquestionably the case that how psalms have been employed has varied based on time, place, and context. Monks in Palestine preferred to read full psalms, for example, while Hagia Sophia in Constantinople preferred to employ verses with refrains. Scholars such as Alexander Lingas, Fr. Job Getcha, and Fr. Robert Taft S. J. have given accounts of how our current liturgical practice synthesizes monastic and urban practices from centers such as Constantinople and Palestine.

In the contemporary North American context, the multiplicity of Orthodox jurisdictions and cultures does not allow for a single generalization of practice. Take the Vesperal invitatory psalm, Psalm 103. On any given Saturday evening, a worshiper in a church of Slavic heritage might encounter excerpts of it being sung chorally; an Antiochian parish might have somebody read it simply and quickly; a Greek psaltis might chant it slowly starting from “When you open your hand, it is filled with good…”, with so-called “Trinitiarian tropes” and the refrain “Glory to you, O God: Alleluia” closing off each verse.

While no one generalization is possible, it does seem fair to say that some jurisdictions tend to prefer what they see as a fulness of practice, minimizing — or refusing — abbreviations (although perhaps allowing for the possibility of speeding everything up). For other jurisdictions, perhaps a general tendency may be observed of assuming a certain Anglophone cultural brevity, preferring shorter services and encouraging a set of preferred edits.

(To clarify, I am here speaking of the parts intended to be sung or recited aloud; the matter of the whether or not the priest’s “silent” prayers ought to be silent, and then what that means in terms of execution, is beyond the present scope.)

For the celebration of the Divine Liturgy on a Resurrectional Sunday, the very beginning of the service is a key place where variation may be observed. Following the Litany of Peace, a choir in a community with Slavic roots might well sing some version of what is called the Typika. This consists of Psalms 102 and 145, and then the Beatitudes are sung at the Little Entrance. Depending on the particulars of the parish, the Beatitudes could be interspersed with the reading of troparia. At the same time, in a parish under the Greek or Antiochian jurisdictions will likely sing what are called the antiphons — short refrains, “Through the intercessions of the Theotokos, Savior, save us” and “Save us, O Son of God, risen from the dead, who sing to you: Alleluia”, perhaps interspersed with appointed psalm verses, and then the Resurrectional apolytikion instead of the Beatitudes, possibly repeated with psalm verses.

The variation exists even within jurisdictions and national traditions. The Antiochian Archdiocese’s books are mutually contradictory; a recent annual liturgical guide for the Antiochian Archdiocese once included the Typika in a list of forbidden practices within that jurisdiction, referring to it as an exclusively Russian practice. On the other hand, the Antiochian Liturgikon (3rd edition, 2010), notes the “Typical psalms” as an option, and the Antiochians’ venerable “Five Pounder”, Divine Prayers and Services by the Rev. Fr. Seraphim Nassar, includes the psalms and the Beatitudes, along with the rubric that each of the Beatitudes is to be sung with the “designated piece in the Octoechos”. The books employed by the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese make no particular comment on the matter, and expanding one’s scope to Greek churches abroad does not necessarily lend clarity; the practice of the Patriarchal chapel in Constantinople is to sing the antiphons, but one can also find parishes and monasteries in Greece where the Typika and Beatitudes are sung.

Consulting the 1888 Typikon of the Great Church of Constantinople compiled by George Violakis, the rubrics manual theoretically governing the practice of both Greek and Antiochian parishes, the expected normative practice is very clear: “On every Sunday in the Liturgy are sung indispensably the Typika and the Beatitudes with the eight Resurrection Hymns of the Octoechos[,]” and the antiphons are reserved for weekdays and feast days. Interspersing the antiphons with verses from the psalms of the Typika on Sundays is itself a hybrid practice, attempting to integrate psalmic elements into the brevity of the cathedral-style antiphons without adding the time that a full Typika and Beatitudes would add.

The Antiochian Archdiocese’s annual Liturgical Guide and the National Forum of Greek Orthodox Church Musicians’ Liturgical Guidebook have taken encouraging steps in this direction by including the antiphon verses, but surely this is not all that ought to be done. I offer the modest proposal that the re-introduction of the Typika and Beatitudes into the liturgical life of Greek and Antiochian parishes in America is an opportunity to address Fr. Ephrem’s and Dr. Lingas’ critique and restore complete psalms to the Divine Liturgy, follow the Typikon in a fuller manner, and to unify inter-jurisdictional practice on Sunday morning. Antiphonal chanting of Byzantine settings of the psalms is quick and exuberant, and the common versions are simple enough to be learned quickly (even by a congregation if desired). Along with the syllabic prosomoia, or hymns sung to a common model melody, that accompany the Beatitudes, this approach establishes a joyful momentum at the beginning of the Divine Liturgy that more than makes up for any additional time added to the service. In addition, is often said that for the Orthodox, every Sunday is a little Easter; the Beatitudes troparia will add substantively to the Sunday celebration’s resurrectional character. Per the Violakis Typikon, the antiphons would continue to be chanted on weekdays and feast days.

Typika: Psalm 102

Typika: Psalm 145

Beatitudes: First Mode with Resurrectional Troparia

The question of language is, of course, central to any discussion about liturgical practice in America; there are common settings in Greek, Romanian, and Slavonic at least, but infrequency of use has made Byzantine settings of the psalms in English and metered texts for the Beatitudes troparia a low priority for composers and translators. At issue with the psalms is that the English text of the psalms themselves are a tough nut to crack for composers; Greek and Slavonic simply have more syllables with which to give the text a melodic drive. However, in recent years, English-language settings of the psalms have been made available by both St. Anthony’s Monastery, using King James-style English, and Fr. Seraphim Dedes, using modern English text. Fr. Seraphim has also begun publishing metered texts for the Beatitudes troparia through the AGES Initiatives website. (In the interest of full disclosure, I am an employee of AGES Initiatives.) These are but the tip of the iceberg; others are currently working on additional compositions that make the Typika accessible to Anglophone cantors and congregations. For Greek and Antiochian parishes with choirs, there are several choral settings of the psalms and Beatitudes available in English employing a Slavic choral idiom, although that I am aware of nobody has yet attempted to set the Resurrectional troparia for choir. The model melodies are certainly simple enough to be sung in unison by a choir, but perhaps a choral composer will be inspired to find a different solution. As we get used to singing these psalms and hymns, surely we will find better ways of singing them.

Such an effort of re-integration will fail before it even begins if church musicians, however well-intentioned, attempt this without communication with the priest. Priests who might wish to implement this would likely do well to consult their bishops, and also work with their cantors and choir directors to make sure that they are adequately prepared to execute the Typika and Beatitudes skillfully and smoothly. Certainly, I do not encourage any church musician to do this without express permission from the priest, and I do not encourage any priest to foist it on an unwary cantor, choir director, or bishop for that matter. Change occurs slowly in the Orthodox Church, of course, and an overnight imposition from anybody is the last thing I am advocating.

Nonetheless, I do encourage church musicians and priests to consult with each other, consider seriously the possibility of incorporating the Typika and Beatitudes into the liturgical life of their parishes, and to think about what it could look like. Perhaps it could be an occasional practice or a slow, gradual integration; “all or nothing” need not be the sole options.

At the very least, the resources now exist and are available in English; this means that more of us can now start thinking about how to incorporate these elements rather than dismissing the notion out of hand. Let us consider together this opportunity to give biblical psalmody and resurrectional hymnody a joyful voice in the Sunday Divine Liturgy.

SCORES

AGES Initiatives: http://www.agesinitiatives.com/dcs/public/dcs/booksindex.html

St. Anthony’s Monastery: https://www.stanthonysmonastery.org/music/Johnchrys.htm#Typicac

LITURGICAL RESOURCES

The Psalter According to the Seventy. Brookline: Holy Transfiguration Monastery, 2008.

Moore, Fr. Lazarus. The Psalter. Madras: Diocesan Press, 1971.

Nassar, Fr. Seraphim. Divine Prayers and Services of the Catholic Orthodox Church of Christ. New York: Syrian Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese of New York and All North America, 1961.

Sheehan, Donald. The Psalms of David: Translated from the Septuagint Greek. Eugene: Wipf & Stock, 2013.

Violakis, George. Typikon: The Ritual Order of the Services of the Great Church of Christ. Bilingual Edition. Highlands Ranch: The Greek Orthodox Metropolis of Denver Church Music Federation, 2015.

FOR FURTHER REFERENCE

Bp. Demetri. “Foreword.” In Christ in the Psalms, by Fr. Patrick Henry Reardon, vii–viii. Ben Lomond: Conciliar Press, 2000.

Getcha, Fr. Job. The Typikon Decoded: An Explanation of Byzantine Liturgical Practice. Crestwood: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2012.

Taft, Fr. Robert F. The Byzantine Rite: A Short History. Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 1992.

From what I’ve seen in a number of Russian-heritage parishes (OCA, ROCOR) the typical psalms are sung but severely truncated. E.g. three quarters of Psalm 102 are cut out. I even brought this up to some monks at an OCA monastery and they didn’t realize that this practice wasn’t universal. “You mean on Mount Athos they sing all that stuff about your youth being renewed like an eagle’s?” In my own parish (ACROD) we vary between the antiphons and the typika- but the typika psalms are truncated. So I’m not sure if substituting the typika for the usual antiphons will actually introduce more psalmic material unless you want people to actually quadruple the amount of time it takes to sing them, something not even the hardcore Slavic parishes do.

It depends on how you sing them, of course. Byzantine settings, like the ones linked to in the piece tend to be quick and syllabic. Done this way, you’re not talking about more than a few minutes’ difference.

Thanks Richard for such an informative article. I’m all for reintroducing liturgical practices that have fallen to the wayside. Especially when it comes to the Psalms.

However, I find Fr. Ephrem Lash’s “cheeky statement” very problematic. It obviously presupposes a false dichotomy between the Psalms and the so called “‘important bits’ by some monks.” In other words, he’s disdaining the ‘important bits’ as what can be called Byzantine ‘frivolous accretions’, in an attempt to ‘uphold’ Scripture. Moreover, in doing so he’s disparaging of monasticism. All of this sounds a bit Protestant to me.

However, let’s not forget that the hymnography of the monastic saints functions as commentary on Scripture — it is, in fact, a theology in full harmony with the Psalms. The hymnography of the saints reveals depths of meaning that for many of the laity tends to go unnoticed. As with the Psalms, the hymnography composed by saintly monks is also inspired by the Holy Spirit. Hence, we should be careful not to introduce ideas which imply that this hymnography is somehow not an integral part of the Tradition. If we are careful to keep this in mind then any attempt at reintroducing edifying liturgical practices will indeed unfold within a truly Orthodox ethos.

Thanks again for your helpful insights.

If we really want to respect the hymns of the fathers we should, for instance, bring back Saint Romanos’ full kontakia instead of embedding snippets of them in canons and forgetting the rest. And it’s really a disgrace that the great works of Saints Romanos, Ephrem, etc are ignored in favor of so many mediocre akathists.

Also, I have to take exception to calling “protestant” the idea that we might want to delve more into the psalms that were the meat-and-potatoes of all the great hymnographers and saints of the church, especially since Fr Ephrem (a monk, by the way) is not proposing that the work of hymnographers be cut out.

I am very glad this is becoming a discussion. I have wondered about the various practices for some time now.

Fantastic article Richard. I will say that I agree with Fr. Silouan that the quote from Fr. Ephrem+ made me more than just a little uncomfortable. What monks was he talking about? Romanos? Kassiane? I am with you though– more Psalms. Why not during Communion? If one is doing more than just “Of Thy Mystical Supper”, then I believe the other hymns should be Psalms only. Anyway, thanks for a great article.

Thank you for your kind words, Frank! Regarding Fr. Ephrem – he put a great deal of effort translating the liturgical poetry of “some monks”, so I don’t think he meant to devalue the work of Ss. Romanos, Kassia, et al. in any way. However, to give but one example of what I think he meant, there are parishes in the Greek Orthodox Metropolis of Boston that omit the Six Psalms at Orthros, and I am given to understand that this is far more common than anybody will talk about (and we don’t hear about it because attendance for Orthros is always so slim). And yet, these same parishes would never omit the Katavasiae, even though the Katavasiae as we do them today are completely divorced from their liturgical and poetic function. Something seems not quite right there.

And yes, Communion is a great place for more psalmody. Psalm 148’s first line is the the Sunday Communion verse, “Praise the Lord from the heavens”; the entire psalm can be chanted as a responsorial, much as presented on the Cappella Romana Divine Liturgy in English recording.