Similar Posts

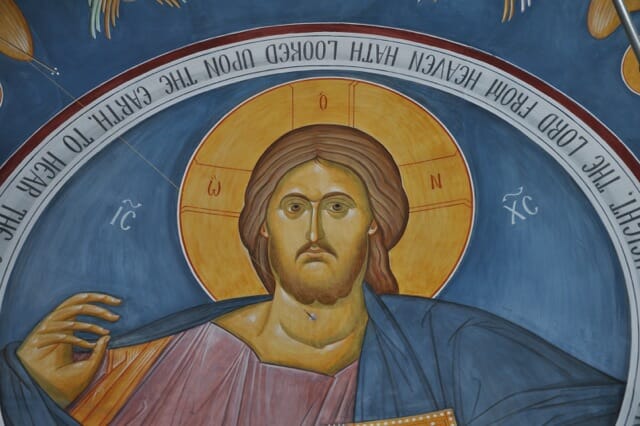

Iconographer Fr. Patrick Doolan and his assistant, Father Moses, continue their extraordinary fresco work at St. Seraphim of Sarov Orthodox Church in Santa Rosa, CA (OCA). They have recently completed the angel range of the dome. (The first phase – the Pantocrator – was described in this article from last fall.) These photos show their work over the past five weeks.

Posted in Iconography

When you look at him drawing, you really get the sense of how subtle his understanding of clothing is, so much more than what we so often see in contemporary iconography. He has all the “tropes” of iconographic clothing but infuses them with complexity and movement.

It’s so amazing & wondering. First time I saw it I was in awe. I’ve never even seen a Seraphim my whole life until here. 🙂 It will be so intriguing when finished. Bless your wonderful work Orthodox believers.

Please take this question as sincere even though I am a proud person:

Why do we have so many angels when their countenances seem to reveal just the same soul duplicated over and over? Are angels like that? Do we just not know?

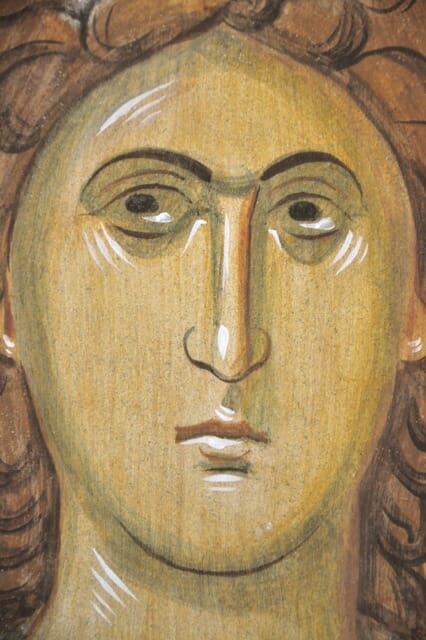

That’s an interesting question. It is true that they all have roughly the same face in iconography. But remember that angels do not have any physical body in reality, and thus no ‘actual’ appearance. On the few occasions when angels appeared visibly to human witnesses, they appeared as young men. We can presume that this is because they wanted to be understandable as messengers or soldiers working for God, and messengers or soldiers would be young men. Since we have no records of the details of their faces, they are painted with the generic idealized face of a young man that was the style in Greek art. It is the same face seen on pagan Greek depictions of athletes and heroes.

But we do know something about the various orders or ‘choirs’ of angels, and their respective roles. Iconography depicts these variations not through facial appearance but through dress and other attributes. Some angels are traditionally shown in Imperial Byzantine court dress, as messengers. Others are shown as soldiers. Sometimes they are dressed as deacons. There are also mysterious conventions like the four heads of beasts shown on the cherubim that support God’s throne, and other places where angels are depicted as winged wheels. Some of this imagery goes back to ancient Babylonian religion.

Put simply, we know very little about angels with certainty, but there a lot of conventions for how to depict them that have become canonical in iconography. There is no point in trying to dissect which conventions have an underlying spiritual reality, and which are simply artistic conventions for the convenience of the painter.

Thanks for the response, Andrew. It’s a logical explanation you’ve given but I still can’t say I’m satisfied on the emotional/relational level with this ring of angels. Are some icons just for the brain, not the soul?

I’m not a theologian, and am treading somewhat outside my expertise here, but I think your distinction between the brain and the soul is not consistent with the Orthodox understanding of icons. The traditional understanding is that spiritual understanding of icons happens in the nous, loosely translated as ‘heart’ in English. To understand icons in one’s heart (the deepest and most holistic understanding) implies correct interpretation with the brain and a parallel sort of communion with the soul.

Now it’s important to understand that iconographic murals on walls are meant to be seen altogether as a building-wide composition. It is in this context that they work most effectively on the heart. Indeed there are some elements of mural icons that are quite hard to see in detail for being up so high, and there are elements that are mysteriously symbolic like the ‘prepared throne’. There are even elements that are downright evil, like Satan in the west-wall ‘last judgment’. Elements such as these are not meant to be venerated. They are not figures of saints with which we can commune in prayer. But their presence is important in that they add narrative and hierarchy to the whole. Specifically, those angels in the dome increase the impact of the Pantocrator above, by showing that Christ’s authority and power is above even the angels.

So broadly speaking, the answer to your question is ‘yes’ – those angels are not meant to be individually venerated like a panel icon of a compassionate saint. They are meant to be a little stand-offish and intimidating like the high-ranking military officers that they are. Their job is to magnify the glory of God of above them.

But I wouldn’t say that this artistic device is only for the brain. Rather, it is a very natural and intuitive effect that could be understood even by someone with no prior knowledge of Christianity. My own experience of visiting a medieval church in Russia frescoed with thousands of compositions is that my brain is quite confused, but my heart is overwhelmed with beauty.

I’m glad you mentioned military officers. I think you nailed it there. The icons of these angels are impressive, beautiful, convey symbolic meaning like military uniforms – some being decorated variously according to individual characteristics, but on the whole presenting a unified and intimidating front. This is part of the iconographic tradition that I feel uncomfortable with but probably need to come to terms with. I want the Pantocrator and his armed forces to be more sensitive and personal and less scary.

What do you think, this is a crazy idea – was the pantocrator in the dome more appropriate in an age when man was relatively more subject to the forces of nature, in need of reminders that the most holy trinity was above all and guiding all. That power would have been a comfort to a vulnerable world.

Now we are in an age in which man exercises relative dominion over creation and abuses it. Does modern man need a different image of God in the dome now? One that is more sensitive rather than powerful? I’m not saying a radical change, but a millimeters change in the eyebrows and line of the mouth.

Christ is not only lord of all creation but also he is the body of the world, right? When we commit violence against an animal or a square foot of soil or sky aren’t we committing it against his body?

You bring up a very interesting issue in liturgical art. From a spiritual and theological standpoint, we can never believe in modernism (the idea that people today are fundamentally different from people in other ages). But nevertheless, we can recognize that people do perceive things differently because of their varying life experiences. And modern people see many things very differently from medieval people. The Church needs to react to this with great caution. On the one hand, we need to offer people liturgical art that will be an effective good influence on their spiritual state. Thus we should avoid things that are so esoteric as to be incomprehensible. On the other hand, we must not dumb down liturgy to a modern level, because our mission is to bring people up to Christ’s level.

Ultimately, I think that your suggestion has merit – that modern people may be more receptive to simpler compositions and more compassionate faces, whereas medieval people were more receptive to complexity and hierarchy. I think it is obvious looking at the modern iconography of Ouspensky and Kroug that these men agreed with this premise. But again, I emphasize caution because it is so easy to confuse what we like with what we need. I think it is important that these kinds of shifts in liturgical art happen slowly and organically, in a natural and unspoken way, rather than through the formulation of principles and theories.

Right on, brother. I appreciate your thoughtful cautions.

Congratulations on this magnificent work. I gaze in awe at the size, beauty and precision of your work. Blessings Sue